9 April 2024 (Crete) — First, just a brief intro to my writing, since many of you have asked me “what is your process?“.

When I was a wee lad, around the age of 9 or 10, I started a weekly neighborhood newspaper – interviewing my neighbors, following local events, etc. One of my Mom’s friends ran a typeset print shop and he helped me design and set-up production. He eventually added a mimeograph machine to his business which made production and distribution of my weekly paper much easier. He eventually got me a job on our town’s local newspaper, running a newspaper delivery route (by bicycle). I eventually built it to over 100 customers. When I got older, the paper hired me as a freelance reporter. The newspaper biz got into by blood.

At university I joined the radio station. In 1972/1973 I was studying at the University of Paris. My university radio station asked me to call in a report on the Vietnam peace talks. There I was, standing outside the Hotel Majestic on 27 January 1973, as the peace accords were formally signed and announced – not really grasping the history unfolding. Later in my career, after law school, I went to journalism school and to film school.

I am by profession a lawyer, a writer, a journalist, a media producer – and in my wildest dreams, a historian. As a lawyer I began my career working for clients in the technology, media, and telecom (TMT) sectors. I stayed in those sectors. It drew me to my own video and film production work, and although I am now semi-retired so I could write more, I still produce a bi-monthly newsletter for my TMT clients while my media team continues to produce bespoke videos for those clients. And I have jumped in and out of my genocide/Holocaust/perpetual-war blog and video series. It has been frustrating, and horrific.

But with the explosion of social media, the continuing Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces and the dispersion of creativity came the development of wonderful curation tools to parse a tsunami of information so readily available. Like most of my media cohorts, I don’t “read” Twitter or Linkedin or any mainstream social media anymore. I use APIs like Cronycle and Factiva that curate the whole social media firehose so I only receive selected, summarized material that pertains to my immediate research or reading need. That led me to develop my own company, Luminative Media.

But really, if you look back at the development of digital media since the turn of the millennium, artists have been writing, and circulating their writing, like never before: essays, criticism, manifestos, fiction, diaries, scripts, and blog posts have charted a complex era in the world at large, away from mainstream social media, weighing in on the exigencies of our times in unexpected and inventive ways.

What is different is the level of social media toxicity and mis-information/dis-information/mal-information. And so one needs to set up some rules:

1. I use media (traditional or social) to become aware of things, but certainly not to reach conclusions on anything. What’s included and excluded, and takes upon it, are always subjective on anything as important as today’s catastrophes. As I have noted many times, to be an informed citizen is a daunting task. We move through myriad, overlapping spheres, ones that are forever entangled. All moving at an exponential pace. We are living through social and technological change on the scale of the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution. But occurring in only a fraction of the time.

Plus, what we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority, primarily but not exclusively governmental – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one. All of these other features are just the localized spikes on the longer sine wave of history. You need to do a lot of homework to get things right.

That is why, as I have noted, my media team and I receive and/or monitor about 3,500 primary and secondary resource points every month (about 120 items each day). But we use an AI program built by my CTO (using the Factiva research database + four other media databases) plus APIs like Cronycle that curate the media firehose so we only receive selected material that pertains to our current research needs, or reading interest, which is coupled with an AI that summarizes each item, and links to the original source.

2. I make it a point to pay most attention to sources which are primary or near-to-primary as possible. So I read cover-to-cover the judgments and the official statements. And so far as journalism is concerned, I only pay attention to the most credible investigative type of material, based on documents and testimony from people directly involved, or people I have known and trusted through the years.

3. In considering official documents about serious allegations, serious matters, you need to pay attention to the precise wording to discover what is not being said, what agendas are hidden. What’s accepted (expressly or implicitly), what’s denied, what’s avoided, what’s recharacterised-then-denied. What’s between-the-lines. All those subtleties give clues as to where the real sensitivities and issues are.

But sometimes (sigh) you just step back and try to sense the humanity of it all. Which brings me to the main topic of this post (finally).

l spent the last few days watching hours of videos of the devastation of Ukraine as chronicled over the last 2+ years, the Russian efforts to make the country unlivable, uninhabitable. And I have read scores of testimonies of Ukrainians under siege, as well as their critics – the later often talking about things they know nothing about, their time better spent thinking about some of the challenges Ukrainians face. And I thank Ukrainians Ivan Matveich and Roman Shermata for sharing their most inner thoughts with me.

1. The most combat capable age is 18-25 years old. But youth is also the future of any country. Would you send them to fight or would you try to preserve their lives?

2. Would you risk being a “free speech absolutist” or censor potentially harmful enemy-inspired media resources?

3. Would you run an election in the midst of war to maintain democratic order, knowing that most likely it will be exploited by an enemy?

4. Would you be transparent about realities of war and losses to your population or would you try to hide it behind heroic epic stories, to motivate the resistance?

5. Would you increase taxes to finance the defense? What % of your budget would you allocate to defense and what % to maintain your economy and infrastructure?

6. You have run out of volunteers, in particular for the infantry. Would you mobilize people by force? If so, how do you make this process fair? Is life of a truck driver worth just as much as that of a famous university professor?

7. Would you shut the border and prevent men from leaving the country even if they don’t want to fight?

8. Would you try to centralize decision making authority to speed up the processes at a risk of being called a dictator?

9. If you make a mistake in any of the choices above, would you recognize it and display vulnerability and weakness or would you project confidence, knowing that you made a mistake?

We all want somebody who knows exactly what he’s doing in a matter as delicate as war. But really … is there anybody like that at all?

Everyone, everywhere, lives by a story. This story is handed to us by the culture we grow up in, the family that raises us, and the worldview we construct for ourselves as we grow. The story will change over time, and adapt to circumstances. When you’re young, you tend to imagine that you have bravely pioneered your own story. After all, the whole world revolves around you.

As you age, though, you begin to see that much of what you believe is in fact a product of the time and place you were young in. It was a study of the First World War that turned it around for me. It was monumental in scope, larger and more devastating than anything in anyone’s experience. The factors leading up to it were a confusing tangle of alliances, feuds, and rivalries, and the ordinary person might be hard-pressed to say just what they were fighting for. So many had died, and for what?

Oh, the complexity of the world. And the faux social environment that rewards simplicity and shortness, and punishes complexity and depth and nuance. I simply detest it. To understand the world you need to step outside your usual lanes, and cross disciplines, and cultural boundaries.

And I get it. It ain’t easy. I realize that many of my readers are “commerce monkeys, commerce machines” (not my turn of phrase – provided by a long time reader) – with barely enough time to read and write and produce for your jobs. You barely have time to scan and parse social media to keep up-to-date. I know. I know.

As I noted earlier in this post, to be an informed citizen is a daunting task. We move through myriad, overlapping spheres, ones that are forever entangled. Moving at an exponential pace – living through social and technological change on the scale of the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution. But occurring in only a fraction of the time.

What we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority (primarily but not exclusively governmental) and the breakdown of all norms – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one if you read your history. All of these features are, really, just the localized spikes on the longer sine wave of history.

But still … everything seems broken and we struggle with “why”, we struggle to understand, we struggle to survive. We are in the formative years of a new period whose name and character we don’t yet know.

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters”.

– Antonio Gramsci

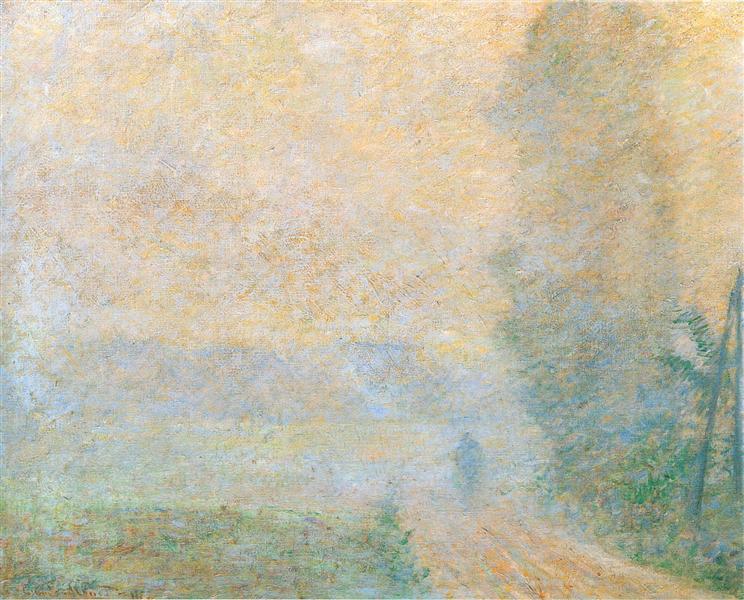

Path in the Fog, Claude Monet, 1887