16 December 2019 (Paris, France) – And we come to the close of a decade. As the decade began, there were reasons to be optimistic: America had elected its first black president, and despite a global recession just two years earlier, the world hadn’t cascaded into total financial collapse. Obamacare, for all its flaws, was passed, and then came the Iran deal and the Paris climate accords. Sure, there were danger signs:

* in the U.S., the anger of the tea party

* in Europe the stirrings of nationalism once again

* the slow hollowing out of legacy news media as the new “workrate” (providing a bonus-for-page-views-structure, the logical outcome of ad-driven internet journalism) started print and journalism into a downward spiral

* a troubling sense that somehow “man, those damn bankers just got away with it!”

But then maybe the immediacy of social media gave some hope, at least if you listened to the chatter of the bright young kids in the San Francisco Bay Area trying to build a new kind of unmediated citizenship. Maybe everyday celebrity, post-gatekeeper, would change the world for the better. Some of that happened.

But we also ended up with the alt-right and Donald Trump, inequality, impeachment, and debilitating FOMO. And micro-targeted content. Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitter, YouTube – oh, man, were we stupid. It’s really should not have been hard to see where the Connected Era was headed.

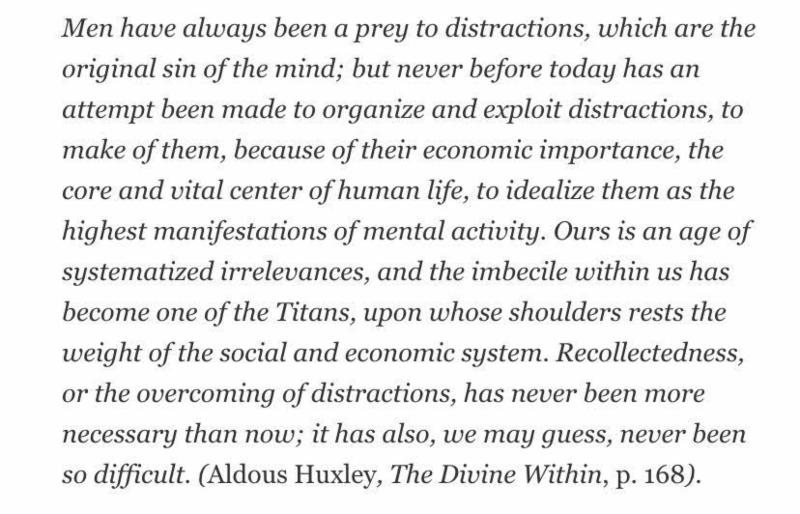

Yes, I am sure the intent of these male Wunderkids was to show netizens a well-rounded, balanced view of the world, through links, ads and posts in news feeds, social networks and similar sites. But those with other intents realized the platform could also be used to create addicts, and feed them a diet of slanted information that taps into their prejudices, fuels their fears, and manipulates their knowledge and feelings to political or commercial ends. All of this was made possible by using their personal and private information, feeding on their fear, their prejudice, their distraction.Hmm. Where have I heard that before? Ah, yes, Aldous Huxley:

How did we get here? How did the Internet expand the horizon so that every utterance or expressive act is taken to a potentially planetary level? There’s a passage in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises which sums it up although in a different context. A character named Mike is asked how he went bankrupt and he says:

“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

The 2010-2019 decade saw the explosion and true impact of social media, for good and bad. Mostly bad. We realized its algorithmic amplification was simply optimized for outrage. It means favoring the extremes, the conspiracy theorists, the histrionic diatribes on all sides. It means fomenting mistrust, suspicion, and conflict everywhere. We’ve all seen it. We’ve all lived it.

The Connected Era

The Social Decade, which fulfilled Marshall McLuhan’s promise, if not threat, of a global village, managed to do two contradictory things at the same time: bring us closer together while also tearing us apart. See: 2016 U.S. Presidential election.

If the late 20th century was about the sound bite, the 2010s were about the connectivity engendered by Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube.

And while we get an endorphin rush when someone likes a post or retweets our trivial thoughts, the Connected Era also meant that companies morphed into brands, anthropomorphic representations of capitalism. We just loved getting @ replies from businesses, especially after we complained to and about them.

In 2011, more than 2 billion people used the internet, and 4.6 billion people worldwide had mobile phones. By the end of the decade, there were 4.5 billion poor souls online and 3.5 billion people worldwide had a smartphone.

Connectivity took over our lives. We are connected to more people than at any time in the history of the world (thank you, Facebook!); we have the answers to any possible question at our fingertips (thank you, Google!); we can watch television on our phones. OUR PHONES! Huxley and Orwell battled it out during the 2010s. As Neil Postman wrote in 1985:

“Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. … In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.”

We can’t say we weren’t warned.

Google, for example, introduced its panopticon Google Glass in 2013 with the promise of bringing a screen closer to your eyes. While this device didn’t catch on, other technological advancements picked up where it left off.

The number of Internet of Things devices increased 31% year over year to 8.4 billion in 2017, and it is estimated that there will be 30 billion devices by 2020. Of course, the one question companies seem to not ask themselves while they are building out “smart” appliances: Do we really need a refrigerator to text you that you left the door open?

And while companies are still trying to figure out how to turn dumb devices into smart ones, I saw the effects of a connected world every day in very interesting ways. My grandchildren know zip about linear TV. But they sure know Hulu and Netflix. None of them watch TV. They use their phones and iPads. They don’t know what a radio is or a turntable. They know Alexa (introduced 2014) though it is not permitted in their homes. No matter. Jeff Bezos is not suffering from the lack of sales from my family. Over the last six years, the number of smart speakers (Amazon’s Alexa, Google Assistant, etc.) has skyrocketed. In December 2018, 118.5 million U.S. households owned at least one device, up from 66.5 million the year before.

It’s not hard to see where this all heads

In 1998, Aaron Sorkin, writing for the NBC hit series The West Wing, said these words through one of his characters:

“The next two decades are going to be privacy. I’m talking about the internet. I’m talking about cellphones. I’m talking about health records and who’s gay and who’s not. And moreover, in a country born on the will to be free, what could be more fundamental than this?”

Society spent the 2010s catching up to Sorkin. But at what cost? We are being tracked through these devices whether we know it or not. Flipping the Huxley/Orwell script, the next decade will see, through AI and facial recognition, a return to a Big Brother.

And while tighter legislation on data collection is on the horizon – the California Consumer Privacy Act, for example, begins on January 1, 2020 – one thing is clear: it’s already far, far too late.