Kissinger’s philosophy constitutes a rough guide to his statesmanship: its origins lay in his experiences as a young Jew in Hitler’s Germany and as the son of immigrants in challenging circumstances

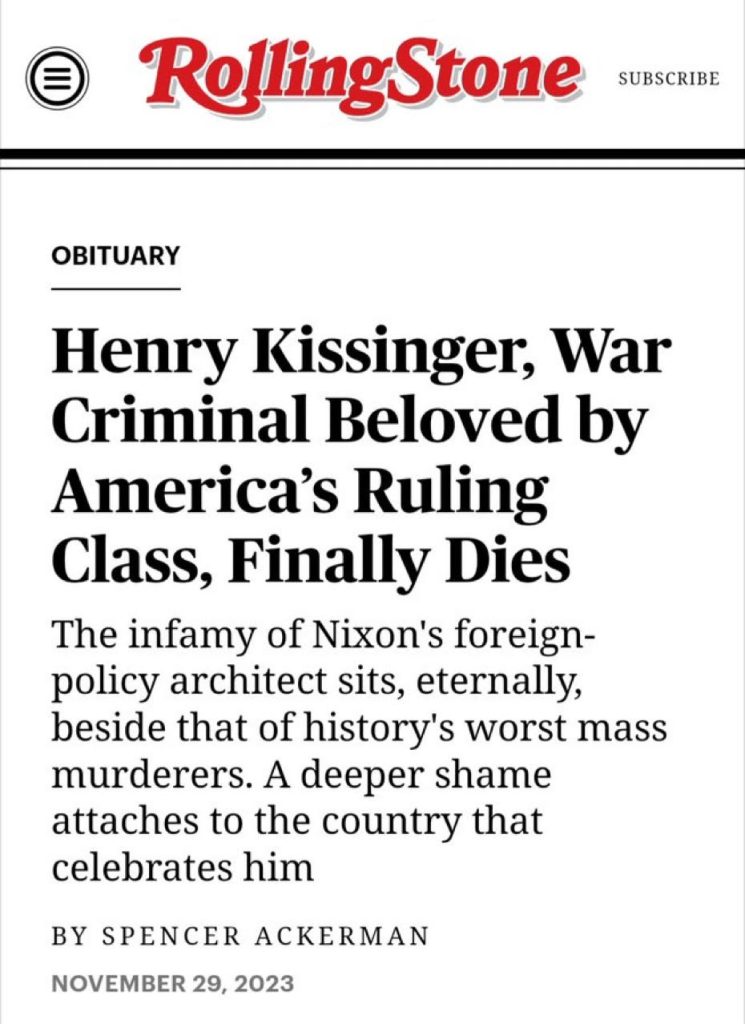

ABOVE: an interesting take, a common headline. But it avoids the complexity.

1 December 2023 — Henry Kissinger died a few months after his 100th birthday. The many eulogies for the celebrated American statesman and diplomat cast the century of his life as an age unto itself – spanning the horrors of the fascism he fled as a young German Jewish refugee, through the Cold War upon he which he put his defining geopolitical imprint as the right-hand man to former president Richard M. Nixon and into a brave new world marked by the inexorable rise of China and the dizzying implications of new technologies like artificial intelligence.

Into the last year of his life, Kissinger remained a figure of prominence and relevance, a doyen of the Washington foreign policy establishment and, through his lucrative consultancy group, a frequent soothsayer to power. Generations of policymakers marveled at the clarity of his insights and the sheer force of his intellect. “If it is possible for diplomacy, at its highest level, to be a form of art, Henry was an artist,” wrote former British prime minister Tony Blair.

Having spent so many years reading about his life and reading his own memoirs, I have come to see that he requires a kind of Cubist treatment. Like Picasso’s Desmoiselles d’Avignon, you need to see him from multiple angles at the same time fully to comprehend him. And just as only the 20th century could have produced Picasso and made his vision not merely intelligible but wildly popular, so no other century could have produced a man like Kissinger.

But for so many people outside the West, Kissinger’s legacy is hardly admirable. There is so much: Kissinger’s direct role in the merciless carpet bombing of Cambodia and indirect enabling of the genocidal rampages of the Khmer Rouge; his “peace agreement” with North Vietnam allowing for the “timely disengagement” of U.S. troops, knowing North Vietnam would eventually overrun South Vietnam; his ruthless pursuit of the exigencies of the Cold War, tolerating and abetting hideous violence around the world. His hand could be seen, among other places, in the dirty wars of right-wing Latin American juntas, in tacit support for white-supremacist minority governments in Africa, and in greenlighting the Indonesian dictatorship’s 1975 invasion of East Timor, which led to a conflict and famine that left as many as 200,000 people dead on the small island. Notwithstanding Kissinger’s many diplomatic achievements and the widespread celebration of him as a world statesman that accompanied his later life, there are many around the globe who revile Kissinger for the role they believe he played in world events. Indeed, a number of his critics have branded him a war criminal and called for his prosecution, and you just need to read Niall Ferguson, Barry Gewen, Christopher Hitchens, Martin Indyk and a host of others for the full history. Obituaries this week will largely attempt to explain the various writers’ views (usually disagreements) with Kissinger’s decisions and the consequences of those decisions.

But we need to engage with the ideas that motivated Kissinger. As Robert Kaplan has noted “The aim of policy is to reconcile what is just with what is possible. Journalists and freedom fighters have it easy in life since they can concern themselves only with what is just. Policymakers, burdened with bureaucratic responsibility in order to advance a nation’s self-interest, have no such luxury.”

That is not to say Kissinger is exempt from criticism or even condemnation, but at least he deserves a fair historical trial.

Because as I noted above, Kissinger’s philosophy constitutes a rough guide to his statesmanship: because it is a philosophy whose origins lay in his experiences as a young Jew in Hitler’s Germany and as the son of immigrants in challenging circumstances.

In fact, Kissinger had internalized the lessons of the Holocaust, though they were different lessons from those learned by the liberal elite of his era. Kissinger saw Hitler as a revolutionary chieftain who represented the forces of anarchy attempting to overthrow a legitimate international system, as imperfect as it was. For in Kissinger’s mind, his first book about the diplomatic response to another revolutionary chieftain, Napoleon, offered a vehicle for him to deal, albeit obliquely, with the problem of Hitler. Morality and power couldn’t be disentangled, in Kissinger’s mind.

In fact, Kissinger, as a practitioner at the highest levels of US foreign policy during some of the hardest days of the Cold War, thought more deeply about morality than many self-styled moralists. As Walter Isaacson notes in “Kissinger A Biography” :

The ultimate moral ambition during that period was the avoidance of a direct military conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union through a favourable balance of power. The Cold War may now seem ancient, but for someone like myself, who as a journalist covered Communist Eastern Europe, with all its grim, freeze-frame poverty and pulverising repression, it will always remain quite vivid. And were it not for Kissinger’s realpolitik, which allowed for a truce with China in order to balance against the Soviet Union, even as he and President Richard Nixon achieved détente with the Kremlin, President Ronald Reagan would never have had the luxury of his subsequent Wilsonianism.

Indeed, Kissinger was a “realist internationalist”, like the other great Republican secretaries of state during the Cold War, George Shultz and James Baker III. Realists today have drifted toward neo-isolationism, and have grown literally smaller because of it. Kissinger’s beliefs, which emerge through his writing, are certainly not for the faint-hearted. They are emotionally unsatisfying, yet analytically timeless. They include:

• Disorder is worse than injustice, since injustice merely means the world is imperfect, while disorder tempts anarchy and the Hobbesian nightmare of war and conflict, of all against all.

• It follows, then, that order is more important than freedom, since without order there is no freedom for anybody.

• The fundamental issue in international and domestic affairs is not the control of wickedness, but the limitation of self-righteousness. For it is self-righteousness that often leads to war and the most extreme forms of repression, both at home and abroad. It is why Donald Trump and his MAGA cult are such a threat.

• The aim of policy is to reconcile what is just with what is possible. Journalists and freedom fighters have it easy in life since they can concern themselves only with what is just. Policymakers, burdened with bureaucratic responsibility in order to advance a nation’s self-interest, have no such luxury.

• Pessimism can often be morally superior to misplaced optimism. Pessimism, therefore, is not necessarily to be disparaged.

It is true that much of the above is derivative of the great philosophers, especially Hobbes. But it is to Kissinger’s credit that he consciously activated it in the daily conduct of foreign policy.

Of course, Kissinger continues to be hated because of Vietnam. But as strange as it may seem, Kissinger and Nixon, in withdrawing from Vietnam in the bloody manner that they did, demonstrated real character: they believed that they were serving the national interest and proving their toughness to China and the Soviet Union, even as they knew they would be vilified in the media, in all the books written by liberal historians, and in the opinion polls for acting thus. Their bloody and methodical withdrawal in the face of liberal demands for total and immediate capitulation and a conservative flight from reality (a belief in fighting till victory) had a demonstrable effect in terms of America’s reputation for power in China, the Soviet Union and the Middle East. For Nixon and Kissinger’s foreign policy was all of a piece. You cannot disentangle Kissinger’s brilliant peace-making in the Middle East from his actions in Indochina. Nevertheless, the withdrawal from Vietnam was still faster than De Gaulle’s from Algeria, for which the French leader has been lionised by historians.

As for the judgment of history, Kissinger’s own memoirs (I have read all of his books), with all of their faults, are vaster, more elegantly written, and far more intellectually stimulating than those of any other American statesman of the period. Kissinger may not have the last word, but he will have something close to it.

Kissinger was a “genuine statesman”, to use the German philosopher-historian Oswald Spengler’s definition: that is, he was not a reactionary who thought that history could be reversed, nor was he a militant-idealist, who thought that history marched in a certain direction. Kissinger’s conclusion was more grounded: he believed less in victory than in reconciliations.

It seems to me that Kissinger was a disciple of Machiavelli. All politics is the art of the possible and a statesman’s duty to serve the long-term interests of the nation he represents. No doubt Kissinger would have agreed with the aphorism “that the road to hell is paved with good intentions”. And while most are viscerally rebelling against Kissinger, the public figure, I find it difficult to offer any arguments against the statements and positions I laid out. It’s infuriating but invigorating, I would say: I am forced to rethink assumptions, and that at least is healthy.

Yes, Henry Kissinger. A very clever person, a master of politics and power, and yet he left so many scars upon it. But you cannot make any conclusion unless you could consider who would have been in their place. Although – well – that principle is not going to get us far as then all of history would have to be binned, because we can never know what would have happened if “x” never happened.

Looking back, 1975-2016 was an age of idealism, but those ideals created problems with no ideal solutions, only practical compromises and retreats from pure ideals. I fear Kissinger will be judged even more harshly as his detente strategy with China has now backfired. To my mind, his strategy was sound at the time, and indeed worked mostly as intended – until Xi Jinping came to power. Xi has upset a lot of apple carts and well on his way to being a historical villain of Napoleonic proportions.

But my point is we have far, far too many idealists and not enough realists in policy these days, both foreign and domestic. Perhaps it’s inevitable. Success breeds complacency and peace, fertile soil for the growing of idealism, then the failures of those ideals cause hardships which can only be fixed with imperfect, pragmatic solutions. The coming year will show how brutal the current world is, and how empty we are of “solutions”.

And a short note: I had three personal encounters with Kissinger. No, I never met him but they were “encounters” just the same:

• On January 27th 1973 I was outside the Majestic Hotel in Paris when the “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam” (known as the “Paris Peace Accords”) was signed. My professor at the Université Paris-Sorbonne (where I was pursuing a degree as part of my university studies) was a former diplomatic affairs officer at the French foreign service and was able to finagle a few spots for a few of us across the street in the “non-press” section. No, I did not understand the import of the day. The negotiations had been going on for weeks and we had simply lucked out and got spots on January 27th – hearing the cheers as “the deal” was announced.

• Three years later I was working as a currency trader at Solomon Brothers in NYC and my Managing Director (a majordomo in the Republican Party) invited me to hear Kissinger speak at a benefit at the Waldorf-Astoria. Two things impressed me: the size of Kissinger’s security detail (he was Secretary of State at the time) – and how many rows back from the stage us lower-level folks had to sit.

• In 2014 his book “World Order” came out (in my opinion his finest book) and my publisher’s consortium had me write a review. The consortium goes back to my university days when I had a long-time, part-time position as a “professional reader” of unsolicited manuscripts submitted to publishers (Random House and then Simon & Schuster). I’d read the manuscript and prepare a “no-longer-than-5-pages” summary. Through this consortium I still receive about 10 books a month – the paperback versions sent to reviewers well before publication. Some books stay in my library, but the majority go to my Foundation which distributes them to libraries.