24 September 2023 — Early in the morning of this day, 24 September, in 1941, a series of huge explosions tore through the German-occupied capital of Ukraine. Resulting in the near total destruction of the Wehrmacht’s military headquarters, the blasts — it transpired — were a “parting gift” from Russian Red Army engineers, who, prior to evacuating Kiev (now known as “Kyiv”), had rigged the building with dynamite, assisted by Soviet secret police still in Kiev.

Two days later, the city’s military governor — SS-Oberführer Kurt Eberhard — convened a meeting with his fellow SS leaders, to discuss how they should respond to the bombings.

Concluding that “Russians and Jews are one and the same”, they decided that responsibility for the attacks lay firmly with Kiev’s Jewish population. And so they determined that it was the Jews of Kiev who had “to pay…”

To that end, a decree was issued that ordered “All Kievan Jews… to appear on Monday 29th September” — the eve of Yom Kippur — “at the corner of Melnikova and Dokterivskaya streets.”

There, they were instructed to “bring documents, money, and valuables”. Those who refused “did so on pain of death”.

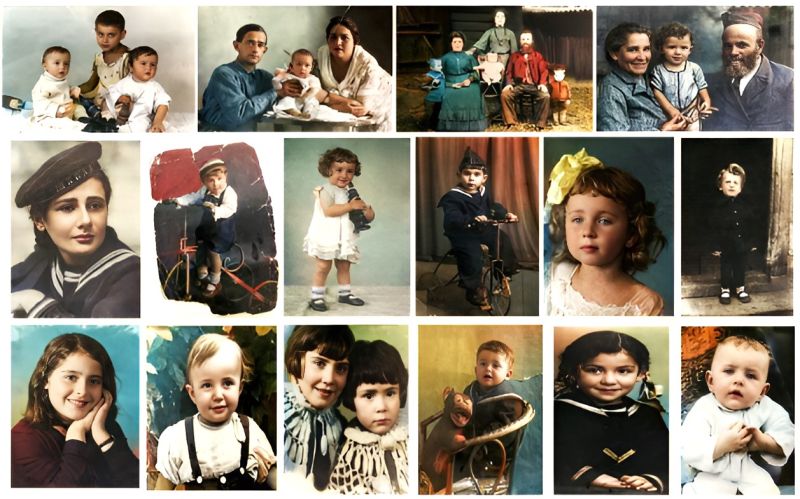

Believing that they were to be “resettled” in far-flung, eastern regions of Hitler’s Reich, nearly 34,000 Jewish men, women, and children packed as much as they could carry, and duly made their way toward what they thought was the beginning of a brand-new life.

It was only when they were ordered to surrender their belongings did they sense that something was wrong. Tragically, it was only when they arrived at their final destination of Babi Yar did they realize, they’d reached the point of no return.

Stripped of their clothing and marched at gunpoint to the precipice of the ravine, it was there that German SS and Ukrainian auxiliaries lined them up in their masses, forced them to their knees, and murdered them with the utmost brutality.

Those who resisted were beaten to death with rifle butts and spades. Those who tried to escape were “shot like targets on a range”. And as for those for whom there were no bullets left, they were thrown into the corpse-filled gully alive, buried with layers of sand, soil, and chloride of lime.

When the killing stopped 36 hours after it began, Kiev was declared:

“Judenfrei”

And yet, in the weeks and months that followed, the Germans and their Ukrainian allies not only found another 70,000 Jews to murder in Babi Yar but they then forced Jewish prisoners to exhume the martyred bodies, and burn them in a heinous attempt to conceal their horrific genocide.

In the years since, some, reprehensibly, have sought to rewrite the history of Jewish suffering in Ukraine; others, shockingly, have even gone so far as to deny it.

For those reasons, the poignant words of Ukrainian poet Mykola Bazahn (who dedicated his life to keeping the truth alive) seem all the more important to memorialize:

For Babi Yar, there can be no penance,

For this fire, there is no measure of revenge.

Be cursed, he who dares to forget!

Be cursed, he who tells us: ‘Forgive!’

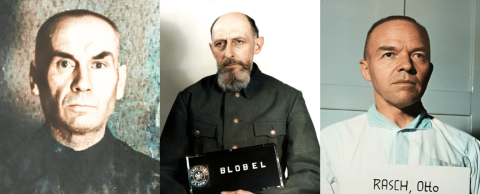

The three men SS-Oberführer Kurt Eberhard convened to discuss how they should respond to the bombing of the Wehrmacht’s headquarters in Kiev (pictured above) were:

-

SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln

-

SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel

-

SS-Brigadeführer Dr. Otto Rasch.

Captured by the Russian Red Army on 28 April 1945, Jeckeln was then tried by a Soviet military tribunal in Riga, Latvia, whose judges found him guilty of the deaths of more than 100,000 Jewish men, women, and children.

Executed by hanging on 3 February 1946, he declared he viewed his sentence “as worthy punishment” for his crimes.

As for Rasch and Blobel, both were indicted at the “Einsatzgruppen Trial” in Nuremberg, Germany, where, on 5 February 1948, Rasch escaped justice when the case against him was dropped due to his “rapidly deteriorating health.”

Three years later, in 1951, Blobel was hanged at Landsberg Prison with the blood of over 60,000 Jewish men, women, and children on his hands.

“Whatever I’ve done”, he said, as he was led away from the courtroom, “I did as a soldier who obeyed orders…”

Asserting that he “committed no crime”, his final words to the court were:

“I will be vindicated by God and history. God have mercy on those who murder me!”

ABOVE: German firemen battling the fire at the Wehrmacht’s ruined headquarters on 24 September 1941 that was caused by the “parting gift” of dynamite left by Russian Red Army Engineers.

In addition to dynamiting the Wehrmacht headquarters building, the Russians also rigged a number of other buildings in Kiev’s government district to explode, resulting in a series of explosions spanning more than a week.

Although senior intelligence officers of the German Abwehr (Germany’s main military-intelligence service) are said to have warned their counterparts in both the Wehrmacht and the SS that explosives had most likely been planted in the buildings they billeted, the Abwehr’s warnings were ignored, owing to an arrogant under-estimation of the Russians’ capabilities.

As a consequence, German soldiers proved easy targets for the Russians. According to German military archives, over 300 German military personnel were killed, and 100s more injured.

ABOVE: Mikhail Matveev

One of the very few Jews who survived the first massacre at Babi Yar was Mikhail Matveev who, remarkably, managed to crawl his way out of the corpse-filled ravine when the first wave of killing stopped.

Shortly after his escape, he enlisted with the Russian Red Army, whose soldiers he fought alongside in his wish to avenge the brutal murder of his family.

ABOVE: a long-distance photograph showing Jewish men, women, and children being forced to surrender their possessions and undress, before then being marched to the precipice at Babi Yar where they were murdered.

Hundreds of photos were discovered by the Russian intelligence service upon the recapture of Kiev. Every photograph had dates and details of what the photograph showed, what German or “Hilfswilliger” commander was in charge, etc.

ABOVE: helpless Jewish men and women can be seen kneeling at the precipice of the main Babi Yar ravine at a massacre in early 1942.

ABOVE: soldiers and officers of the Russian Red Army showing American and Russian war correspondents just one of the countless mass graves they uncovered at Babi Yar, following the liberation of Kiev in November 1943.

In addition to the ravine shown above, it is believed there were more than 1,500 known murder sites used to massacre Jews during the “Holocaust by Bullets” in Ukraine.

PHOTO BELOW: Photographs taken by Russian war correspondents following the liberation of Kiev in 1943, showing wide-sweeping views of 4 locations where Kievan Jews were murdered at Babi Yar.

ABOVE: this detailed map illustrates some of the massacre sites used from June 1941 to November 1942. The map was reconstructed by historian Anatolii Kuznetsov from notes and records retrieved from German headquarters in Berlin and Kiev, and includes sites beyond just the Babi Yar massacres.

ABOVE: the “Hilfswilliger” (Willing Helpers)

Members of the 115th Ukrainian “Schutzmannschaft Bataillon” (Auxiliary Police Battalion) had a division called the “Hilfswilliger” (Willing Helpers) who participated in the massacre of Jewish men, women, and children at Babi Yar.

There were several battalions recruited from auxiliaries called “Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists” which played a key — if not leading role — in facilitating the “Holocaust by Bullets” in Ukraine.

As time progressed, these battalions expanded their genocidal operations by moving into neighboring towns and villages in German-occupied Belarus and Poland and Russia, where, until their transfer to the Western Front in the spring of 1944, they committed some of the most horrific atrocities of the Second World War.

Although the Provisional Government of French President Charles de Gaulle wanted to deport surviving Ukrainian “Schutzmannschaften” to Russia at the war’s end, some joined the French Foreign Legion — where they knew they’d be immune to prosecution — while many others escaped to Great Britain and the United States, where they never had to answer for their crimes.

ABOVE: the Ukrainian poet Mykola Bazahn

From 1923 onwards, Mykola Bazahn published a series of books and poems, which, by 1926, had earned him wide acclaim and recognition across the former Soviet Union.

As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s, he unexpectedly found himself out of favor with the Soviet Politburo, whose leading members classified his then works as being “anti-Proletarian”.

For a while, therefore, he feared arrest and imprisonment. But thanks to his impressive translation of the stirring “Warrior in the Tiger’s Skin” poem by the famed Georgian poet, Shota Rustaveli, he not only went on to win the praise of Josef Stalin himself but, was even bestowed the Order of Lenin by the “Man of Steel” for “outstanding services rendered to the State.”

Upon Germany’s invasion of the USSR in June 1941, he ventured to the frontlines, where, as editor of the “For Soviet Ukraine” newspaper, he served as a military correspondent through until the war’s end in 1945.

Prior to his passing aged 79 in November 1983, Mykola was well-deservedly nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature.

Sadly, however, the government of Leonid Brezhnev denied him the right to accept his candidature.

For nearly five decades, official policy in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic prevented the establishment of a monument dedicated solely to the blessed memory of the more than 100,000 Jewish men, women, and children who were murdered at Babi Yar.

Thanks to the unceasing efforts, however, of Holocaust survivors and Jewish war veterans, the Communist Party of Ukraine finally agreed to have a Menorah-shaped stone monument erected in their honor.

It was opened on 29 September 1991, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the first mass shooting of Kievan Jews at Babi Yar. But through the years the memorial has been subjected to anti-Semitic vandalism on many occasions, as has the sacred “Road of Woe” that leads up to it.

On 1 March 2022, the complex (which includes both the memorial and the cemetery for victims of the Babi Yar massacre) was hit by a missile attack carried out by the Russian Federation during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.