Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is coupled with a cultural conflict aimed at eradicating Ukrainian identity. We saw it with the Nazis and Jewish culture.

But culture, used as a war weapon by the aggressor, can also serve as a means of defense for Kyiv.

4 JUNE 2023 — The dehumanization, genocide and destruction of Jewish culture during the Nazi era was implemented across several domains: economic, educational, personal, professional, social and religious. On ascending to power in 1933, Hitler and his Nazi party made it clear that there was no place in Germany for any Jew or Jewish culture and that all Jews were to be eliminated from the country.

It was unclear what “elimination” meant in the early stages of these dehumanizing tactics. At the beginning of the Nazi years, elimination was taken to mean coerced emigration. It would expand to isolate Jews from non-Jews by restricting Jewish livelihoods, activities and freedoms – to increasingly convince the German public (the bystanders) that Jews were a separate, subhuman or inferior people that were a menace to Germany. It meant the destruction of synagogues which was paramount to Nazi efforts to compromise a synagogue’s educational, social and religious purposes.

But toward the end of the Nazi era, elimination came to mean extermination through various forms of murder, such as starvation regimens in ghettos, German death squads, and gassing in concentration camps.

The overall Nazi strategy regarding the Jews, therefore, was a policy of elimination that became total extermination, with the ultimate goal that Germany would become a country (and Europe a continent) free of Jews.

There are by now many thousands of studies of how the Nazi regime developed its merciless machine of human destruction. Over the last 5 years of my Holocaust media project I think I have read 375+ books – but a fraction of the Holocaust and genocide literature available in English, which is itself only a fraction of the literature available in Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Polish, Yiddish, and other languages.

We know about Nazi scientists and artists, about censorship and misinformation, about the looting of museums and private collections, and about the many ways the totalitarian German state attempted to remake the cultural landscape of Europe. If you read a book like “The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe’s Libraries” by Anders Rydell, his account of the Nazis’ concerted effort to destroy book collections on Judaism, Freemasonry, Marxism and other subjects, you see the concentrated efforts by the Nazis to attack these elements of European culture and politics. When organized murderers destroy a group’s places of worship or assembly, when they kill in horrific ways, there is nothing surprising about their also destroying property, including books. Although on a far lower level, it is no different than the far right’s attack on American education which I wrote about here.

But Rydell makes the important point that books are not just property, they are “keepers of memories”. Which is why the Russians are burning almost all Ukrainian books in the territories they occupied, replacing them with Russian texts. This was all pre-planned.

Because Rydell sees books as messengers from an all-but-vanished past that can be reunited in the present with the descendants of those persecuted by the Third Reich and its allies. Compared to the valuable paintings stolen by Nazis from their Jewish owners, which after the war became famous cases of restitution, books are much quieter messengers. They are often not worth much to anyone except the family members of those who were killed. But books persist as traces of the lives of those who once pored over their pages, and they recall communities of readers who are no more.

However familiar, the sheer scale of the Nazi effort to destroy the literature of their enemies is staggering. Tens of millions of books were incinerated, buried or simply left to rot in the basements of official buildings. From Amsterdam to Rome, from Warsaw to Paris, soldiers of the Reich hunted down public repositories and private collections. The intensity of destruction was greatest in Poland, where there was a concerted effort to exterminate the entire country’s literary heritage. According to Adolf Hitler’s doctrine, Poles were subhuman. When Polish Jews could be targeted, Nazi officials were particularly motivated. “For us it was a matter of special pride to destroy the Talmudic Academy,” a Nazi soldier noted, “which has been known as the greatest in Poland.”

The Nazis were bent on creating new knowledge and not just on destroying their enemies. This was not an issue of mere facts. To paraphrase a current American commentator on demagoguery, Nazi ideologists didn’t want to be taken literally; they wanted to be taken seriously in their quest for profound truths. “What is more frightening,” Rydell asks, “a totalitarian regime’s destruction of knowledge, or its hankering for it?”

Actually, the Nazi “hankering” for knowledge was far less frightening than its capacity for destruction. Rydell notes that the Third Reich did pseudo-research on witchcraft and witch-burning for its propaganda value in justifying attacks on the Catholic Church. While the research was ridiculous, the grimly efficient engine of annihilation wrecked havoc across the world. That havoc has been described and analyzed by numerous historians before, including Christopher Browning, Saul Friedländer, Phillipe Sands, and so many more. An equally compelling account is the effort to save books, particularly Jewish books, such as Aaron Lansky’s powerful “Outwitting History” which is a stirring account of a young American going to extraordinary lengths to save Yiddish books and Jewish culture from the Nazi onslaught.

And the onslaught continues.

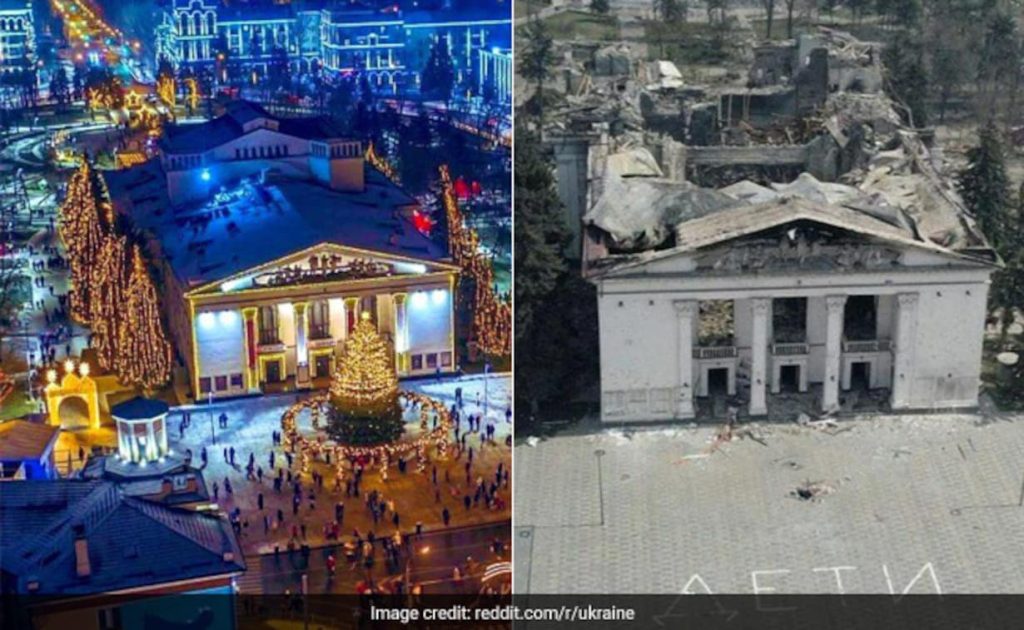

The theatre in Mariupol, Ukraine in December 2021, and in March 2022 after the Russian authorities destroyed it. Over 700 Ukrainians had sought shelter in it. It was completely bulldozed to cover up the murder of those civilians, a screen erected around the ruined theatre to hide the bulldozing.

Besieged, residents of Mariupol, Ukraine sought spontaneous refuge in the spring of 2022. Some sought safety in the city’s Dramatic Art Theater, others within the city’s Philharmonic Concert Hall. These were familiar and almost comforting places amidst the unrestrained violence that was raging, yet they weren’t spared. The theater, a target of air strikes, tragically became a mass grave for hundreds of people – with an estimate of 700 buried victims. The concert hall, also struck, was intended to be the stage for a trial, after the surrender of the Azovstal fighters who had held out for weeks in a nearby huge steel mill. Metal cages were set up for this purpose but were never used. The Ukrainian defenders ultimately became part of a prisoner exchange. However, the theater and concert hall had yet to see the end of their encounter with the Russian occupiers.

Less than a year after these tragic events, bulldozers got to work destroying what remained of the theater, shielded from view by a tarpaulin featuring the stylized profiles of Pushkin, Tolstoy, Gogol, and, in the right corner, as a cruel endorsement, that of Taras Shevchenko, the great Ukrainian poet of the 19th century (1814-1861), exiled and persecuted under the Russian Empire. On the 18th of March, following the warrant issued against him by the International Criminal Court for “war crimes,” *Vladimir Putin* (a body double according to the U.S. intelligence) made an appearance in the martyred city of Donbas, allegedly setting foot for the first time in one of the new Ukrainian territories annexed by Russia. Arriving by night, by helicopter, from Crimea, *the Kremlin leader* walked down Metalourhiv Avenue before sitting, satisfied, in one of the bottle-green armchairs of the reconstructed concert hall. Culture is one of Russia’s weapons of war.

“Everything related to the development of the cultural sector in the new constituent entities of the Russian Federation and their integration (…) is an absolute priority for us,” explained the Russian Culture Minister, Olga Lyubimova, a few days later, on the 23rd of March. In a lengthy interview with the daily newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda, she outlined her medium-term mission: the opening of “model” libraries. “We will purchase 90,000 books every year for each of the new regions” – along with movie theaters, museums, a concert tour called “We Are Russia,” teacher training, and the introduction of Russian culture to children through a program named “Pushkin Card.”

I’ll summarise a few points made by Emmanuel Grynszpanin and Isabelle Mandraud from a recent series in Le Monde, along with some reports from the NGO Human Rights Watch.

Erasing the traces of atrocities

In order to “introduce them to the historical cultural heritage of our common homeland,” 10,000 Ukrainian students will visit various emblematic sites of Russia. These include the Plesetsk Cosmodrome (the main launch center for military satellites, 800 kilometers north of Moscow), the Bolshoi Theater in the capital, the Mariinsky Theater, and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. “From the first days of the special military operation,” the minister added, “representatives of our federal museums (…) have been working in the new territories.” In addition to forceful assimilation, there is a clear intention to swiftly erase the traces of atrocities committed by Russian forces. Said Iryna Dmytrychyn, head of Ukrainian studies at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations and translator of many Ukrainian authors:

“Russia has always counterbalanced its barbarity with its culture, it’s a way to dilute its responsibilities. This has always masked a lot in the West, it’s no coincidence that the Russian cultural center opened in Paris”.

On this last point she is (bitterly) referring to the “spiritual and Orthodox” institution inaugurated in 2016 on the banks of the Seine, Quai Branly. It was a project launched a few years earlier under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy, despite the Russo-Georgian war (2008). In light of Russia’s rich cultural heritage, its illustrious writers, its distinguished painters, and its world-class ballets, what transgressions won’t we overlook?

The city of Kherson, the first and only regional capital occupied at the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, had been adorned with gigantic billboards bearing the image of Pushkin before it was retaken by the Kyiv army in November 2022. Alongside the portrait of the great 19th-century Russian writer were these words: “The history of the great poet’s ancestors are linked to this city as it was founded by a well-known member of his family, Ivan Abramovich Gannibal [a Russian naval officer and Pushkin’s great-uncle].”

Then came this quote from the poet: “Ivan Abramovich built Kherson in 1797. Its foundations are still recognized in this southern region of Russia where, in 1821, I met elders who still remember it.” There was no mention here of the fact that, when passing through Kherson, Pushkin himself was being sent into exile, following Emperor Alexander I’s orders, because his works were deemed seditious.

Symbol of imperialism

Pushkin. A Russian soldier now. A Russian friend of mine sent me a scroll of photos of monuments dedicated to the now co-opted poet: a bust on a pedestal repainted with the letter “Z,” a rallying symbol for war supporters, road signs, or a statue surrounded by ribbons of St. George, an imperial order that has become, since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, an emblem of Putin’s expansionism. The most famous Russian author is now seen as the primary symbol of Moscow’s imperialism. In Kyiv, Chernihiv, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, Kramatorsk, and dozens of Ukrainian cities, his statue has been toppled. This wave of dismantling has been so extensive that it sparked a movement, termed by Ukrainians as “Pushkinopad,” meaning “fall of Pushkin.”

The situation is particularly ironic considering that in Russia, Pushkin Square in Moscow has been, since the 1960s, a focal point for those opposing the regime. On February 24, 2022, the first protest of Russians against the war also congregated at the foot of the statue, on which another quote is inscribed: “I praised freedom in a cruel era.”

Too many deaths, too much destruction and too much hatred are now associated in Ukraine with the language of the enemy. In a remarkable essay titled “Taking Pushkin off his pedestal,” published on the 12th of April on the website Engelsbergideas.com, British analyst Thomas de Waal, a think tank scholar at Carnegie and an expert on the Caucasus, strives to demonstrate the use of the poet as a “state product,” from imperial Russia to the present day, through the USSR, despite his many facets. “To demolish the statue of Pushkin is to challenge Russia as a whole,” he noted. After Lenin, whose countless statues have been removed from Ukraine, as in so many other former USSR republics, it is now Pushkin’s turn to disappear.

Cultural plundering is rife

Famous or not, other Russian writers and authors are being removed, one after another, from libraries. Not a single bookstore in Kyiv displays a book in Russian in its storefront anymore. Ukrainians are distancing themselves from a language, which gave Putin a pretext as early as 2014, to violently invade their territory. Few voices call out “do not confuse the infamies committed by the current Russian regime with the works of Russian authors, often outcasts, and almost always tragic prophets in their own country.” No one wants to hear that.

Since then, Russian rockets and artillery have continued their devastation. A single missile was enough to destroy the house-museum-library of a favorite Ukrainian writer and philosopher, Hryhorii Skovoroda. No one believes for a second that it was a targeting mistake. In the classic military tradition, artillery fire was followed by an artillery assault to make sure the destruction was complete. We find a similar two-stage strategy in the Russian offensive against Ukrainian books and Ukrainian literature. In the occupied territories, where the Russians exercise their power, there are still many libraries to be destroyed.

The looting of cultural property is also rampant. As the Russian forces retreated from Kherson after nine months of occupation, driven out by the Ukrainian counter-offensive, they took everything with them. Thousands of pieces of artwork and cultural artifacts from the city’s art museum, the regional museum, Saint Catherine’s Cathedral, and the region’s national archives were loaded onto military trucks and taken across the left bank of the Dnipro River. Paintings, gold, silver, ancient Greek artifacts, religious icons, and historical documents have all disappeared, according to the NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW): “This systematic looting was an organized operation aimed at depriving Ukrainians of their national heritage and amounts to a war crime, for which the perpetrators should be held accountable,” said Belkis Wille, the deputy director of the crisis and conflict Division at HRW. The same raid took place in the city of Melitopol.

Damaged or destroyed sites

And then there is the simple, continual, arbitrary destruction. According to the latest census conducted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as of 2 May, 254 Ukrainian cultural sites have been damaged or destroyed since the beginning of the invasion, “deliberately,” according to independent UN experts.

These include 109 religious buildings, 22 museums, 91 historical and/or artistic buildings, 19 monuments, 12 libraries, and one archival site. The estimated damages amount to $2.6 billion (€2.35 billion). According to the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture, the number of damaged sites was already assessed at 468, including 35 museums and 44 libraries, as of August 2022. During her visit to Kyiv on April 3, Director General of UNESCO Audrey Azoulay estimated the additional needs at $6.9 billion to assist the threatened Ukrainian heritage. Special attention will be given to the digitization of museum inventories, which are crucial for identifying artworks when they go missing but have often been carried out on paper until now:

“This visit corresponded to a pivotal moment, where the Ukrainian authorities have expressed their determination to rebuild without waiting for the end of the war. Volodymyr Zelensky has prioritized culture, not in terms of propaganda, but rather in terms of social cohesion, to support and restore hope to the population. The appointment of four deputy ministers alongside the Ukrainian Culture Minister Oleksandr Tkachenko is a testament to this concern and the intensified efforts in this field. Concerts and temporary exhibitions are being organized, even in partially closed venues such as the Khanenko Museum in the capital, whose windows were shattered by a rocket that fell less than 10 meters away. It is a reaction, almost an assertion. A form of resistance”.

The “Shot-Down Renaissance”

Faced with the Russian offensive in the cultural sphere and the denial of Ukrainian identity, the counteroffensive is not limited to the realm of words or protecting artworks alone. Many Ukrainian artists and intellectuals have enlisted, either in the army or as volunteers. “Now, the cultural sphere looks like some kind of massive air battle – so many pilots shot down,” said the writer Serhiy Jadan on Twitter on 14 April. It’s another battlefield.

The 40-year-old conductor Kostiantyn Starovytskyi fought in Brovary, in the Kyiv region, and then near Kharkiv, before serving in the Donbas, in the east of the country, where he was killed during Russian bombardments on the Kramatorsk area. His name joins a long list of artists who have disappeared since the beginning of the Russian intervention in Ukraine. Dancers, such as Artem Datsyhyn or Oleksandr Chapoval, musicians such as Nikolai Igorevich Zvyagintsev, pianist of the Donetsk orchestra killed in combat, or Yuri Kerpatenko, who conducted the chamber orchestra of the Kherson Philharmonic, and who was shot dead at his home by Russian soldiers. These deaths bring the past back to the surface.

One of the most popular themes among Ukrainian intellectuals today revolves around the concept of the “Shot-Down Renaissance.” This term refers to the devastating repression that artists faced in the 1930s, following a flourishing period that emerged after the brief existence of an independent Ukrainian republic a decade earlier. Among them were notable figures such as writer Mykola Khvyliovy, leader of the literary association Vaplite, Mykhailo Semenko, the initiator of Ukrainian futurism, and Yuri Yanovsky, whose novel The Four Sabers (1930) was prefaced by Louis Aragon in 1957. A hundred years after this truncated “Renaissance,” the prevailing sentiment is that history repeats itself, and that a new resurgence was abruptly halted by the Russian invasion. The list of martyrs is being unearthed and history is being re-read.

Martyr artist

For resisting Russian influence, the writer Taras Shevchenko, deeply attached to his homeland despite enduring multiple oppressions as a serf in Russia, is revered. His name, given in 1999 to the largest university in Kyiv, appears on countless monuments. Since the invasion launched by the Kremlin in February 2022, Vasyl Stus’s name, too, resurfaces strongly in the speeches of intellectuals as another example of a martyr artist. As a poet and Ukrainian dissident, he was imprisoned multiple times and died at the age of 47 in the Perm-36 Gulag in 1985 during Gorbachev’s era.

After his final arrest in 1972, his lawyer stood out by advocating for a longer sentence than the one requested by the prosecutor. That lawyer was Viktor Medvedchuk, who later became an oligarch and a powerful pro-Russian politician. As a personal friend of Putin, he was arrested by Ukrainian authorities during the war before being exchanged for prisoners.

The identity of prominent artists born in Ukraine is now being debated within the context of Russian culture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (MET) recently renamed 19th-century painters, including Ilya Repin and Arkhip Kuindzhi, as “Ukrainian” in its catalogs, whereas they were previously labeled as Russian. The Petit Palais, for not having done the same, faced strong criticism after hosting a superb exhibition of Repin’s works in Paris during the winter of 2021-2022. Similarly, two prominent museums, the MET and the National Gallery in London, have reclassified one of the pastels by the French painter Degas from “Russian Dancers” to “Ukrainian Dancers.” The London Museum justified the change by stating, “It is almost certain that these dancers are Ukrainian” since they are depicted wearing crowns in the national colors of yellow and blue on their heads.

But what about all the other cultural giants? Gogol, Bulgakov, Malevich? In Kyiv, the debate is growing over whether to write “Mykola” Gogol instead of “Nikolai” because, by reactivating the Cossack identity, his important role in the Ukrainian awakening is now recognized.

Just like Repin, who not only painted the Zaporozhian Cossacks but also included a small portrait of Shevchenko on the wall in his painting “They Did Not Expect Him,” which depicts the return of a prisoner to his home. On the other hand, despite being born in Kyiv, Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940) is seen as an imperialist, especially for his novel The White Guard. He is now being rejected, much like Pushkin. The museum dedicated to him in the center of the capital, located in the house where the author of the marvelous The Master and Margarita lived, is threatened with closure. At Taras Shevchenko University, his commemorative plaque has been removed.

Reclaiming your identity

Said one Ukrainian art historian “We are in the process of decolonizing an empire that, like others, reduced a country to a secondary, provincialized status. At the end of the 18th century, Russia abolished all Ukrainian particularities, and until the early 20th century, there were no fine arts or music schools. If you wanted to be known, you had to go to the ‘center,’ meaning Moscow or Saint Petersburg. Ukrainian creators had no other choice.”

This domination has persisted. He said: “During the time of Death and the Penguin – a post-Soviet satire written in 1996 that achieved international success – I was asked to rewrite history, not in Kyiv but in Moscow. I refused. Russia has always tried to assimilate everything that was next to it”.

To understand the overlap and intricacies and Byzantine relationships of Russian and Ukrainian culture, society and politics start with “The Gates of History” by Seri Plokhy.

After Ukraine gained independence during the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the population’s thirst to reclaim their identity along with their culture continued to grow. The authorities in Kyiv had even begun to take an interest in language protection policies, such as the quota system in France. However, the war initiated by Russia in 2014 in the Donbas region transformed this aspiration into a determination to break away. Ukrainians are now fighting against the resurgence of Russian colonialism and meticulously documenting all the violations against their culture, in accordance with the 1954 Hague Convention that safeguards cultural heritage during armed conflicts.

This convention, ratified by 134 states, was complemented by a protocol adopted in 1999 following numerous conflicts that arose in the past decade. Its aim was to punish serious violations committed against cultural property which can be deemed war crimes. So far, there has been only one precedent in this field: in 2016, jihadist Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi was sentenced by the International Criminal Court to nine years in prison (but was released after serving seven years) for his involvement in the intentional destruction of the mausoleums in Timbuktu, Mali. Ukraine is determined to bring several cases before international justice, including the Mariupol theater case.

The list is growing. On 25 April, the small local museum in Kupiansk, in the north-east of the country, was blown to pieces by a Russian missile, killing two people, including the guard. There was no other building in the immediate area. A “barbaric” attack, said Zelensky, and as he pointed out, yet another “war crime.”

And so it will continue. Libraries, architectural treasures, statues, churches, houses of culture, museums, cinemas, sports facilities, theaters and archaeological sites to be damaged or destroyed. The attempts to eliminate a people, a culture. Cultural destruction and genocide are as ancient as the inventions of governments and armies. And despite human evolution, these crimes against humanity continue with no notable suspension anywhere on Earth. Human progress has not taken us far enough: we can visit the moon, but somehow, we cannot curb our cruelty toward one another. Although States and individuals occasionally express outrage, too often, attention spans diminish. What we saw committed in the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th centuries continues into the 21st – and sadly likely to continue ad infinitum. With growing tensions related to great power politics and regional politics – but perhaps more to climate change which is intensifying conflicts already facing the world, with stressors such as poverty and political instability magnified by increased droughts, floods, or heat waves— the chances of our living peaceably are exponentially reduced.