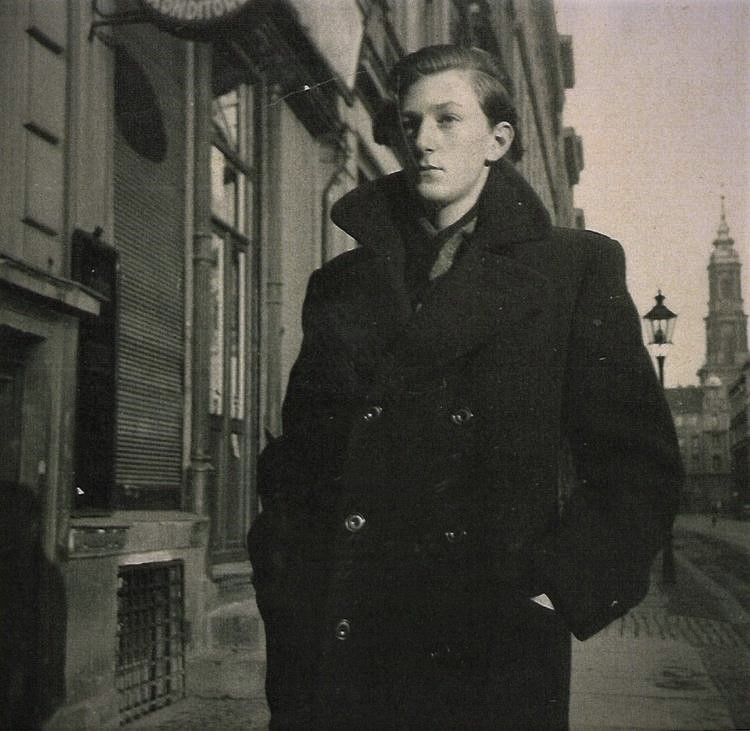

ABOVE: Cioma Schönhaus

29 September 2022 – Over the last 5 years I have been involved in a film project that has been the most challenging of my career. It has been a deep dive into the political uses of dehumanisation, genocide and massacre, with a primary focus on the life of Jacques Semelin, one of the world’s leading authorities on these subjects. Here is the first trailer we did a few years ago:

But the project was delayed due to COVID, during which time it was also expanded significantly. The movie has been changed a bit to reflect what I have learned from my filming at the Auschwitz death camp, and my visit to the Galicia Jewish Museum located in the historic Jewish district of Kazimierz in Kraków, Poland. The Museum does a marvelous job documenting the remnants of Jewish culture and life in Polish Galicia, which used to be very vibrant in this area, and by putting the Holocaust, Jewish culture and world-wide racism in perspective.

And the movie has been changed by the Ukraine War (how could it not?) which most of you follow via my media team’s coverage of that war.

As far as the expansion of the project, besides the primary movie about Jacques Semelin, we’ve created video essays such as:

– “The coronavirus is not the Holocaust” // “Le coronavirus n’est pas l’Holocauste”

– “A conversation with Serge Klarsfeld: the survival of Jews in France” / “Une conversation avec Serge Klarsfeld: la survie des Juifs en France”

– “Some thoughts on Hanukkah”

– “Genocide begins with dehumanisation”

You can view all of these by accessing my YouTube playlist by clicking here.

And the movie has brought me full circle. When I became involved in war crime investigation work over 15 years years ago, I was introduced to Jacques’ work. My mentors told me he was the seminal authority on massacre and genocide. This work has involved 100+ hours of interview time with Jacques plus numerous other genocide authorities, and allowed me unfettered access to the two Holocaust memorials in Paris, the Holocaust memorial in Washington DC, a trip to the death camp at Auschwitz, and an upcoming trip to Yad Vashem. But it also includes study of the genocides in Yugoslavia and Rwanda. What started as one film has now resulted in one major film, plus the videos I noted above – with at least 5 more videos to come.

This work has also included the collection of 1,000s of stories, most of which are impossible to include in the films and videos but which I have begun sharing in a series of posts. The first was about Heinz Drossel (which you can ready by clicking here). He was a 28-year-old lieutenant of the German infantry, sentenced to death, who would survive and marry the Jewish woman whose life he had saved.

The following story is a bit different.

THE FORGER

ABOVE: 16-year-old Cioma Schönhaus with his parents and his grandmother in 1938

Berlin 1942. A young graphic artist had a very special talent that helped many persecuted people to survive the Nazi regime: Cioma Schönhaus was a master forger. His parents were Russian Jews who had settled in Berlin in 1920, where their only son Samson, called Cioma, was born on this day 100 years ago, 29th September 1922.

In 1940 Cioma attended a school of arts and crafts, but was forced to quit and work in the armaments industry only a year later. His parents were deported to Majdanek concentration camp in June 1941 (both perished). Cioma escaped and went into hiding. Together with other Jews in hiding and with support of the Confessing Church of Berlin-Dahlem, Schönhaus started to forge passports and other documents in a workshop he built up with printer Ludwig Lichtwitz. He developed his own method to create these documents with masterful precision.

Like many churches Berlin-Dahlem had an offertory box at the entrance. Usually people left money to support the parish. When rumours spread that someone forged passports for persecuted Jews, people started to slip their passports into the box. Schönhaus used these passports as basic material. His forged passports enabled persecuted people to live with new identities, hidden in plain sight. It is estimated he forged over 2,000 passports. It is unknown how many survived in Germany, fled Germany with those passports, were caught, etc.

The Gestapo got aware of his activities in summer 1943. Schönhaus hid in the flat of Confessing Church resistance member Helene Jacobs. When Jacobs and different others from the network were arrested, Schönhaus managed to escape by bicycle to Switzerland, where he survived the war. In Basel, Switzerland, Schönhaus pursued his studies in arts and crafts and later worked as a graphic artist.

SIDE NOTE: Basel was quite safe. But many were unhappy with Switzerland’s pro-Nazi neutrality during WW II. The Basel Prefect of Police had his own radical way of dealing with the many Nazi agents in the city (due to its strategic industrial importance). He drowned then in the Rhine. Something I picked up when I was trolling Vatican Archive Records for my film. More to come in another post.

In 2004 he published his autobiography in German, and an English translation subsequently became available under the title “The Forger: An Extraordinary Story of Survival in Wartime Berlin”. It is quite the read. In 2017 a film adaption, “The Invisibles” was released.

SIDE NOTE: The movie can be a bit melodramatic in parts (poetic licence) but it is quite riveting. One thing the movie noted but which Schönhaus did not cover in his autobiography is that it is estimated 7,000 Jews stayed in Berlin under cover and at the end of the war there were about 1,500 left. What struck me about this movie was that the quest for survival led many to undertake deeds they would never have contemplated had their lives been normal. And it also shows the Nazi brainwashing machine in its full glory which led to many informants prospering. The end of the war was not kind to the Nazi informers. There is one very emotional scene when the Russian/Jewish soldier makes one of the 4 resistance members prove that he indeed was Jewish, based on several real life stories provided to the producers of the film.

Cioma Schönhaus died in 2015, a few days before his 93rd birthday. In an interview around the time the movie was released, one of his four sons relayed a story. They asked their father “How one can be sure if a decision is right or wrong?” He answered: “Everything that leads to life is good.”

POSTSCRIPT

For those of you who love Klezmer music, two of Cioma Schönhaus’ sons started a band called “Bait Jaffe” (= beautiful house, a translation of Schönhaus) in the 1990s: