Elon’s comical first few weeks at Twitter have gone worse than expected – but most people expected a train wreck so nobody was surprised at the trajectory. Just the speed of it.

But the inevitable collapse of the powerful is a good thing. Read on.

16 November 2022 (Washington, DC) – Ah, Twitter. Every day it’s an all-new magical world of new things to get overly mad about. And now I hear (horror 😱) Twitter might die?

What is there to say about Twitter that has not already been said? What begrudging homage to the platform could be paid that has not already been paid as so many bid farewell to (or at least say they are leaving) the site? I won’t add to much here other than to say we will miss Twitter for one big reason if it goes (see below). And I have not parted with the site myself even though the timeline has become a mess. Like many others, I’ve created an account on Mastodon, but I doubt I’ll ever make an earnest effort to establish a presence there.

And obviously I’ve thought about the place of Twitter in relation to older media. Twitter is jammed with images and gifs and reaction emojis and video clips, etc. But the written word remains central to the experience of the platform. This is, I suspect, one of the reasons that professionals of the word – academics, writers, and journalists, for instance – gravitated to Twitter. For instance, look at this wonderful Twitter thread by Alexis Madrigal which opens with “Something I’ve been thinking about Twitter: for those of us who are word people, this was once our place”.

In retrospect, maybe Twitter will appear as the last gasp, admittedly hybrid and possibly monstrous, of the old print culture in the new digital age. And I suspect this accounts for many of the derangements and absurdities that characterize the platform. Its hybridity – a volatile scrambling of the psychodynamics of orality and print – tempts certain users to navigate its waters by the old norms of print culture, norms which are inadequate to its digital nature. In every way social media is a throwback, combining the worst of prior eras of communication, becoming the inescapable “Town Square” which I covered earlier this year in this post.

AND A NOTE: at this point, in my original draft, I laid out the profound psychic consequences when human societies transition from oral to written communication, and then beyond, drawing attention to how the medium affects not only the means by which we transmit information but also how we think and feel our way through the world.

Had I included that analysis this post would rival “War and Peace” in length. So I shall point you to Walter Ong and his 1982 book “Orality and Literacy”. Ong identified significant eras in the history of human communication, with thresholds between them corresponding to the advent of new technologies — alphabetic writing, the printing press, and electronic media. He contrasted “primary” orality — cultures with no knowledge of writing — with literacy. He then looked at the transition from literacy, and its massive expansion through print media, to what he called a “secondary” orality, the condition brought about by the advent of electronic media, especially radio and television, when sound and visual came to prominence once more alongside the written word. While Ong died in 2003, just as the contours of the digital age were beginning to emerge, his work nonetheless provides us with a set of useful frameworks and insights by which we might make sense of the challenges posed by digital media.

And he got one point dead right: digital technology would scramble all of the earlier dynamics. On the one hand, digital media would “dramatically expand our capacity to document and store information”. He envisioned we would rely ever more on “easily accessible and searchable archives”. He surmised that technology would develop where “you will be able to carry ten thousand images in your pocket, on some sort of device, and you will be able to search them by date and place”. In 1995, Nicholas Negroponte in his book “Being Digital” expanded on this and outlined the history of digital technologies “to be”. As I have noted numerous times in scores of previous posts, Negroponte foresaw almost all of the communication technology advancements we see today.

Twitter is, among other things, a machine for harvesting the attention of users, but it functions in this way partly by exploiting the human desire for attention – an acute desire that, if not channeled or pursued with care, can become the fulcrum on which any one of us might be bent grotesquely out of shape. Twitter strikes me as being particularly well engineered in this respect, but most social media platforms can do the job well enough. To be clear, the dynamic is simply human and characterizes all social life. But social media harnessed this dynamic by making its tacit and organic structures explicit, quantifiable, and programmable.

But few of us ever followed (or understood) the history – how we got from “social networking” to “social media” (two very different things). I will lay out that history (in brief) below.

As far as Twitter dying … eh. I have a rule. I try to be skeptical of the dramatic, confident predictions of immediate catastrophe that fill social media at moments of seeming crisis, which rarely come true and usually sound more like expressions of inchoate desire for chaos than sober assessments of reality. My experience of institutional crisis over the last 40 years of doing this stuff (Jesus, am I that old!) is extensive and overnight collapse is memorable … but rare. And most things (companies, careers, countries, invasions, political parties, supranational economic unions) just slowly decay, intermittently stabilizing along a very long downward trajectory, rather than implode overnight. Inertia is a powerful force, and it takes a lot of work to really kill an established institution.

But Elon Musk is, as they say, on his grind. After Musk’s disastrous first few weeks in charge, I really (really) expected to see some contrition and gestures toward stability this week — or even some signs of minimal executive competence. My rule of thumb about catastrophe being a lengthier process than we might fear (or hope) suggested that, in the immediate term, Musk, a “seasoned executive” and “entrepreneur” (with a hell of a lot of debt to service) could and would stabilize the platform and business he’d sent into a tailspin. Surely he could approach Mohammed bin Salman and say “if you want to keep your spy operation running, I need some cash”.

But the narrative was all wrong. All I heard was this “builder of real companies” (Tesla and SpaceX) who built real products would set things right – and he focused on ads.

All of that sounded good, but on closer examination it was mostly wrong. Obviously better, relevant ads are better, but Twitter’s problem is not just poor execution in terms of its ad product but also that it’s a terrible place for ads. I do agree that giving users more control is a better approach to content moderation, but the obsession with the doing-it-for-the-clicks narrative ignores the nichification of the media. And, when it comes to the good of humanity, I think the biggest learning from Twitter is that putting together people who disagree with each other is actually a terrible idea; yes, it is why Twitter will never be replicated, but also why it has likely been a net negative for society (except for one very positive aspect which I note below). The digital town square is the Internet broadly; Twitter is more akin to a digital cage match, perhaps best monetized on a pay-per-view basis.

Yes, Twitter is a real product – but it has largely failed as company. As I wrote earlier this year when Musk first made a bid:

Ok. Color me baffled. Twitter has had over 19 different funding rounds (and that includes pre-IPO, IPO, and post-IPO), which means it has raised a total of $4.4 billion in funding. Meanwhile (assuming SEC filings never lie) the company has lost a cumulative $861 million in its lifetime as a public company (i.e. excluding pre-IPO losses). During that time the company has held 33 earnings calls; the company reported a profit in only 14 of them. I’ve listed to a few. Same old, same old.

So given this stunning financial performance it beggars belief this company has been valued at $30 billion – and that was the day before Musk’s investment was revealed. Such is the value of Twitter’s social graph and its cultural impact (well, according to “the market”) despite there being no evidence that Twitter can even be sustainably profitable, much less return billions of dollars to shareholders. Ah, hope springs eternal. Surely somebody is on the verge of unlocking its potential. And along comes Mr Musk’s offer to take Twitter private. Get out the popcorn.

But let’s step back a bit and look at the last few weeks, and then move onto some “social networking” and “social media” technology history, and finish with some thoughts about what losing Twitter might mean and where we might be going with “social media”.

The Twitter telenovela, in very abbreviated form:

Elon rode into town with the idea that Twitter’s big problem is spam and bots, and that if you verify users by making them pay you could solve this. Both parts of this are highly debatable, but even if you agree, he made a huge mess of it in less than a week.

The trouble, of course, is that Twitter already has a “verified user” feature that’s free and provided on a discretionary basis to “notable” people, so that you know that’s the real Oprah or the real Obama, for instance. This was never supposed to be a value judgement – but it became that. It was an endorsement.

Yet last week, right after buying the company, Elon added “verification” to the “Twitter Blue” subscription – so now any random Nazi could buy the same blue tick for $8/month, and any prankster could create an account called “RealElonMusk” that bought it a “verified” badge.

Oops. After 48 hours of absolute hilarity the whole thing got turned off. Now (well as of early Wednesday morning as I finally finish this post) there is an “official” label, recreating the old model – but meanwhile the whole idea is discredited.

NOTE TO READERS: One of the more amusing stories was the nine-word tweet sent last Thursday afternoon from an account using the name and logo of the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly: “We are excited to announce insulin is free now”. The Tweet went viral. The tweet carried a blue “verified” check mark, a badge that Twitter had used for years to signal an account’s authenticity — except this badge had just been bought for $8 under Musk’s new program.

Inside the real Eli Lilly, the fake sparked a panic. Company officials scrambled to contact Twitter representatives and demanded they kill the viral spoof, worried it could undermine their brand’s reputation or push false claims about people’s medicine. But at Twitter, its staffing just cut in half which included most of the content management team Eli Lilly needed to speak with, didn’t react for hours. Eli Lilly ordered a halt to all Twitter ad campaigns — a potentially serious blow, given that sources say Eli Lilly spends $30 million plus on Twitter. Other brands followed. Given the massive advertising budgets these companies control, not good if Musk says the company needs to avoid bankruptcy.

This is the problem with being quite so hasty – if Elon had made a new, different badge (even a different color!) instead of conflating the old and new meanings of “verified” this might have been avoided. Did normal people notice? Maybe, maybe not, but the last thing Twitter needs is more confusion about how it works.

But then, even more hilarity. Over the course of last Monday and Tuesday Twitter’s entire senior executive level resigned:

– head of trust and safety

– the company’s de facto head of sales

– the director of software engineering

– the Chief Privacy Officer

– the Chief Information Officer

– the Chief Legal Officer

– the Chief Compliance Officer

And to add even more fun to the story line:

– A good chunk of the security, governance, risks and compliance teams also left

– Musk announced advertisers were fleeing and Twitter might need to file for bankruptcy

– Over last weekend Twitter fired 4,400 of its 5,500 contractors with no notice at all, some of them while they were actually writing mission-critical code covering security, compliance and content moderation

Yes, it is possible to believe both that Twitter was very badly run and hugely over-staffed, with lots of people not doing much, and also that firing 65% of the company in the first month and losing most of your advertising and moderation execs in the process might be just a little careless.

The major social media pundits (all of them very, very good) went ballistic by week’s end, and over this past weekend. Casey Newton was out with “Inside the Twitter Meltdown”, Charlie Warzel was out with “Elon Musk Is Really Bad at This”, and Ian Bogost published an essay titled “The Age of Social Media is Ending”.

I have known Ian Bogost for awhile (he was a professor in one of my media courses). He is best known for his work with Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory which is a theoretical and methodological approach to social theory and explains how everything in the social and natural worlds exist in constantly shifting networks of relationships and posits that nothing exists outside those relationships in a modern world. It explains the ever increasing complexity of social networks and technology’s social infrastructure, basically explaining (even predicting) how social media would and did become dystopian – the Good, the Bad, the Ugly.

Newton and Warzel are quite good but I favor Bogost’s work and I will quote a few key paragraphs from his essay before I run through a (relatively) short history of social media. Bogost’s premise is fairly simple. Now that we’ve washed up on an unexpected shore due to the “shipwreck” of both Facebook and Twitter, we can look back at the shipwreck that left us here with fresh eyes:

Perhaps we can find some relief: Social media was never a natural way to work, play, and socialize, though it did become second nature. The practice evolved via a weird mutation, one so subtle that it was difficult to spot happening in the moment.

The shift began 20 years ago or so, when networked computers became sufficiently ubiquitous that people began using them to build and manage relationships. Social networking had its problems—collecting friends instead of, well, being friendly with them, for example—but they were modest compared with what followed. Slowly and without fanfare, around the end of the aughts, social media took its place. The change was almost invisible, but it had enormous consequences. Instead of facilitating the modest use of existing connections—largely for offline life (to organize a birthday party, say)—social software turned those connections into a latent broadcast channel. All at once, billions of people saw themselves as celebrities, pundits, and tastemakers.

A global broadcast network where anyone can say anything to anyone else as often as possible, and where such people have come to think they deserve such a capacity, or even that withholding it amounts to censorship or suppression—that’s just a terrible idea from the outset. And it’s a terrible idea that is entirely and completely bound up with the concept of social media itself: systems erected and used exclusively to deliver an endless stream of content.

But now, perhaps, it can also end. The possible downfall of Facebook and Twitter (and others) is an opportunity—not to shift to some equivalent platform, but to embrace their ruination, something previously unthinkable.

A long time ago, many social networks walked the Earth. Six Degrees launched in 1997, named after a Pulitzer-nominated play based on a psychological experiment. I know Six Degrees because I worked at the law firm that arranged its funding, Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison.

NOTE TO READERS: Six Degrees was considered be the first real “social network service” because it was based on the “Web of Contacts” model of social networking. It was named after the six degrees of separation concept and allowed users to list friends, family members and acquaintances both on the site and externally; external contacts were invited to join the site. People who confirmed a relationship with an existing user but did not go on to register with the site continued to receive occasional email updates and solicitations. Users could send messages and post bulletin board items to people in their various tiers.

Six Degrees shut down soon after the dot-com crash of 2000 – the world wasn’t ready yet. My old law firm, Brobeck, also shut down. The firm had to liquidate in 2003. It, too, was an “innovator”. Rather than being paid straight legal retainers the firm used to forgo $$$$ and take large angel investor positions and stock positions (after the IPO) in the companies they helped to fund, taking a very small cash percentage for its fees. Great deal in an up market. But when all comes crashing down – not so good.

The founders and engineers of Six Degrees lived on, and Friendster arose from its ashes in 2002, followed by MySpace. LinkedIn launched in 2003. The next year Facebook launched, basically for students at select colleges and universities. That year also saw the arrival of Orkut, made and operated by Google. Bebo launched in 2005; eventually both AOL and Amazon would own it. Google Buzz and Google+ were born and then killed. You’ve probably never heard of some of these, but before Facebook was everywhere, many of these services were immensely popular and laid the foundations for Facebook.

And, yes, yes, yes. It would all eventually morph into sophisticated data feedback systems that would keep us on a treadmill and undermine the essential structures of everyday life, making it steadily harder to behave in thoughtful, civic, social ways. More on that later.

Behind all the drama, Twitter has some pretty basic problems. It’s too small (and the data too weak) for advertisers to need it. There is also a lot of very toxic content – most of it (sorry Elon) comes from very real people and not bots , indeed verified users. And the product is a mess. So a lot needs to change, and some decisions need to be taken … but it would be nice to have some sense that the change comes with a vision instead of a whim.

But let’s go back a bit and look at the foundations of “social networking” and how it became “social media” and “social mass media”, and then take stock where we might be today.

As Ian Bogost noted (see quote above) we saw this shift about 20 years ago or so, when networked computers became sufficiently ubiquitous that people began using them to build and manage relationships. Oh, social networking had its problems – collecting friends instead of, well, being friendly with them, for example – but they were modest compared with what followed. Slowly and without fanfare, around the end of the 2000s, social media took its place. The change was almost invisible, but it had enormous consequences. Instead of facilitating the modest use of existing connections – largely for offline life (to organize a birthday party, say) – social software turned those connections into a latent broadcast channel. All at once, billions of people saw themselves as celebrities, pundits, and tastemakers. As Bogost notes:

Content-sharing sites also acted as de facto social networks, allowing people to see material posted mostly by people they knew or knew of, rather than from across the entire world. Flickr, the photo-sharing site, was one; YouTube – once seen as Flickr for video – was another. Blogs (and bloglike services, such as Tumblr) raced alongside them, hosting “musings” seen by few and engaged by fewer.

But it morphed. Today, people refer to all of these services and more as “social media,” a name so familiar that it has ceased to bear meaning. But two decades ago, that term didn’t exist. Many of these sites framed themselves as a part of a “web 2.0” revolution in “user-generated content,” offering easy-to-use, easily adopted tools on websites and then mobile apps. They were built for creating and sharing “content” – a term that had previously meant “satisfied” when pronounced differently. But at the time, and for years, these offerings were framed as social networks or, more often, social-network services. So many SNSes proliferated (these were “simple notification systems”) that a joke acronym arose: YASN, or “yet another social network.” These things were everywhere.

As the original name suggested, social networking involved connecting, not publishing. By connecting your personal network of trusted contacts (or “strong ties,” as sociologists call them) to others’ such networks (via “weak ties”), you could surface a larger network of trusted contacts. LinkedIn promised to make job searching and business networking possible by traversing the connections of your connections. Friendster did so for personal relationships, Facebook for college mates, and so on. The whole idea of social networks was networking: building or deepening relationships, mostly with people you knew. How and why that deepening happened was largely left to the users to decide.

That changed when “social networking” became “social media” around 2009, between the introduction of the smartphone and the launch of Instagram. Instead of connection – forging latent ties to people and organizations we would mostly ignore – social media offered platforms through which people could publish content as widely as possible, well beyond their networks of immediate contacts. Social media turned you, me, and everyone into broadcasters (if aspirational ones). The results have been generally disastrous – ok, some moments highly pleasurable like my blog – not to mention massively profitable. In all, a catastrophic combination.

The terms social network and social media are used interchangeably now, but they shouldn’t be. A social network is an idle, inactive system – a Rolodex of contacts, a notebook of sales targets, a yearbook of possible soul mates. But social media is active – hyperactive, really – spewing material across those networks instead of leaving them alone until needed.

There is a marvelous paper that was published in 2003 that I quote ad nauseam that made an early case that drives the point home. The authors proposed social media as a system in which users participate in “information exchange.” The network, which had previously been used to establish and maintain relationships, becomes reinterpreted as a channel through which to broadcast. They argued this was the natural progression of such social technology.

But at the time this was a novel concept. When News Corp bbought MySpace in 2005, The New York Times called the website “a youth-oriented music and ‘social networking’ site” – complete with those now infamous scare quotes. The site’s primary content, music, was seen as separate from its social-networking functions. Even Zuckerberg’s initial vision for Facebook, to “connect every person in the world,” implied a networking function – not media distribution.

The toxicity of social media makes it easy to forget how truly magical this innovation felt when it was new. Alex Hern, technology editor for The Guardian, opined:

From 2004 to 2009, you could join Facebook and everyone you’d ever known—including people you’d definitely lost track of—was right there, ready to connect or reconnect. The posts and photos I saw characterized my friends’ changing lives, not the conspiracy theories that their unhinged friends had shared with them. LinkedIn did the same thing with business contacts, making referrals, dealmaking, and job hunting much easier than they had been previously. In 2003, when LinkedIn was brand new, people were inking their first deals simply by working their LI connections.

Twitter, which launched in 2006, was probably the first true social-media site – even if nobody called it that at the time. Instead of focusing on connecting people, the site amounted to a giant, asynchronous chat room for the world. Twitter was for talking to everyone – which is perhaps one of the reasons journalists flocked to it. Sure, a blog could technically be read by anybody with a web browser, but in practice finding that readership was hard. That’s why blogs operated first as social networks, through mechanisms such as blogrolls and linkbacks. But on Twitter, anything anybody posted could be seen instantly by anyone else. And furthermore, unlike posts on blogs or images on Flickr or videos on YouTube, tweets were short and low-effort, making it easy to post many of them a week – or even numerous throughout the day.

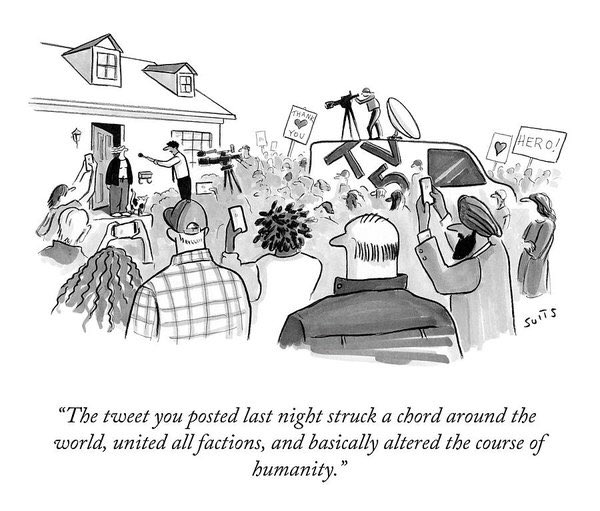

It built the notion of a global “town square”. On Twitter, you can instantly learn about a tsunami in Tōhoku or an omakase in Topeka. This is also why journalists have become so dependent on Twitter: it’s a constant stream of sources, events, and reactions – a reporting automat, not to mention an outbound vector for media tastemakers to make tastes.

But for those of us who are long in the tooth, as we look back at these moments, we realize social media had already arrived in spirit if not by name. RSS readers offered a feed of blog posts to catch up on, complete with unread counts. MySpace fused music and chatter; YouTube did it with video (“Broadcast Yourself”). In 2005, at an industry conference, an attendee said “DAMN! I’m so behind on my Flickr!”

What in hell did that mean? Well now the answer is obvious: creating and consuming content for any reason, or no reason. Social media was overtaking social networking. We had all been pulled into the vortex.

Instagram, launched in 2010, might have built the bridge between the social-network era and the age of social media. At least that was the feeling that year at Cannes Lions, the annual advertising conference (once) famous for its rosé-soaked yacht parties as its agenda-setting discussions and deals. This is the event for the industries and ecosystems in which I have both worked and followed: advertising, digital technology, legal technology, media, mobile technology and software development. Stuff is discussed and developed here that goes mainstream in about 1 year.

Instagram set the pace, relying on the connections among users as a mechanism to distribute content as a primary activity. Zuckerberg saw the threat to Facebook and bought it. But soon enough, all social networks became social media first and foremost. When groups, pages, and the News Feed launched, Facebook began encouraging users to share content published by others in order to increase engagement on the service, rather than to provide updates to friends. LinkedIn launched a program to publish content across the platform, too. Twitter, already principally a publishing platform, added a dedicated “retweet” feature, making it far easier to spread content virally across user networks.

And the floodgates opened. Other services arrived or evolved in this vein, among them Reddit, Snapchat, and WhatsApp, all far more popular than Twitter. Social networks, once latent routes for possible contact, became superhighways of constant content. Bogost has written:

In their latest phase, their social-networking aspects have been pushed deep into the background. Although you can connect the app to your contacts and follow specific users, on TikTok, you are more likely to simply plug into a continuous flow of video content that has oozed to the surface via algorithm. You still have to connect with other users to use some of these services’ features. But connection as a primary purpose has declined. Think of the change like this: In the social-networking era, the connections were essential, driving both content creation and consumption. But the social-media era seeks the thinnest, most soluble connections possible, just enough to allow the content to flow.

Social networks’ evolution into social media brought both opportunity and calamity. Facebook and all the rest enjoyed a massive rise in engagement and the associated data-driven advertising profits that the attention-driven content economy created. The same phenomenon also created the influencer economy, in which individual social-media users became valuable as channels for distributing marketing messages or product sponsorships by means of their posts’ real or imagined reach. Ordinary folk could now make some money or even a lucrative living “creating content” online. The platforms sold them on that promise, creating official programs and mechanisms to facilitate it. In turn, “influencer” became an aspirational role, especially for young people for whom Instagram fame seemed more achievable than traditional celebrity – or perhaps employment of any kind.

The ensuing disaster was multipart. For one, social-media operators discovered that the more emotionally charged the content, the better it spread across its users’ networks. Polarizing, offensive, or just plain fraudulent information was optimized for distribution. By the time the platforms realized and the public revolted, it was too late to turn off these feedback loops.

Obsession fueled the flames. Compulsion had always plagued computer-facilitated social networking – it was the original sin. Rounding up friends or business contacts into a pen in your online profile for possible future use was never a healthy way to understand social relationships. It was just as common to obsess over having 500-plus connections on LinkedIn in 2003 as it is to covet Instagram followers today. Casey Newton:

But when social networking evolved into social media, user expectations escalated. Driven by venture capitalists’ expectations and then Wall Street’s demands, the tech companies—Google and Facebook and all the rest—became addicted to massive scale. And the values associated with scale—reaching a lot of people easily and cheaply, and reaping the benefits—became appealing to everyone: a journalist earning reputational capital on Twitter; a 20-something seeking sponsorship on Instagram; a dissident spreading word of their cause on YouTube; an insurrectionist sowing rebellion on Facebook; an autopornographer selling sex, or its image, on OnlyFans; a self-styled guru hawking advice on LinkedIn. Social media showed that everyone has the potential to reach a massive audience at low cost and high gain—and that potential gave many people the impression that they deserve such an audience.

The flip side of that coin also shines. On social media, everyone believes that anyone to whom they have access owes them an audience: a writer who posted a take, a celebrity who announced a project, a pretty girl just trying to live her life, that anon who said something afflictive. When network connections become activated for any reason or no reason, then every connection seems worthy of traversing.

That was a terrible idea. People just aren’t meant to talk to one another this much. They shouldn’t have that much to say, they shouldn’t expect to receive such a large audience for that expression, and they shouldn’t suppose a right to comment or rejoinder for every thought or notion either. Social media produced a positively unhinged, sociopathic rendition of human sociality. That’s no surprise, I guess, given that the model was forged in the fires of Big Tech companies such as Facebook, where sociopathy is a design philosophy.

The tribe of social media commentators/analysts I noted above – Casey Newton, Charlie Warzel and Ian Bogost – all believe that if Twitter does fail, either because its revenue collapses or because the massive debt that Musk’s deal imposes crushes it, the result could help accelerate social media’s decline more generally. It would also be tragic for those who have come to rely on these platforms, for news or community or conversation or mere compulsion.

Right now Twitter looks like one giant, slow-motion fail whale.

Over the weekend, Elon Musk apologized for Twitter being “super slow in many countries” and then blamed it on “poorly batched RPCs [remote procedure calls]”.

First, let’s get this out of the way now: according to many former Twitter engineers, still on Twitter, this is bull shit. And one long time contact of mine, still at Twitter, told me “having worked on timelines infrastructure at Twitter, I can confidently say this man has no idea wtf he’s talking about”, a feeling echoed by many former Twitter engineers still on the site, and also on a private Slack account full of ex-and-current Twitter engineers to which I have access. And as I noted in a previous post, although this article appeared a week ago, and things have just started to fray at the edges, what this engineer predicted is becoming true.

Plus, the World Cup’s is now starting. That’s going to load-test Twitter in multiple non-Western countries at once. Why? Because while Twitter is breaking down, it is breaking down in different ways depending on how and where you access it – I’ve seen upside down threads, disappearing tweets, my spam filters are broken, and I’ve seen links being incorrectly blocked for malicious content.

But it’s not just falling apart on a structural level, it’s also creating a cascade of bizarre sociopolitical effects across the world. In Japan, the lack of curated news topics has turned the site into 4chan. There are reportedly about a dozen people left working for Twitter in India, where the company is still actively suing the country’s right-wing government over content removal. Twitter Mexico is shut down completely, much to the excitement of Mexico’s left-wing populist president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who celebrated that the “snakes” were gone. Twitter’s entire operation in Africa is also gone. And there are only two people left working for the company in Brussels, literally days before the European Union enacts the Digital Markets Act, which will, among other things, force interoperability between app stores and messaging apps. And as reported early this morning in the European press, the site has already begun violating the EU’s GDPR.

If change in social media structure and operation is possible, carrying it out will be difficult, because we have adapted our lives to conform to social media’s pleasures and torments. It’s seemingly as hard to give up on social media as it was to give up smoking en masse, like Americans did in the 20th century. Quitting that habit took decades of regulatory intervention, public-relations campaigning, social shaming, and aesthetic shifts. At a cultural level, we didn’t stop smoking just because the habit was unpleasant or uncool or even because it might kill us. We did so slowly and over time, by forcing social life to suffocate the practice. That process would need to begin in earnest for social media.

Social networks – the molten core – were never a terrible idea, at least to use computers to connect to one another on occasion, for justified reasons, and in moderation (although the risk of instrumentalizing one another was present from the outset). The problem came from doing so all the time, as a lifestyle, an aspiration, an obsession. It took us two decades to realize the Faustian nature of the bargain. Someday, eventually, perhaps its web will unwind. But not soon, and not easily.

To win the soul of social life, you’d need to learn to “muzzle it” again. Everybody. Across the globe. The billions of people. That’s Bogost again. In another essay on his blog he noted:

We’d need to speak less, to fewer people and less often—and for them to do the same to you, and everyone else as well. We cannot make social media good, because it is fundamentally bad, deep in its very structure. All we can do is hope that it withers away, and play our small part in helping abandon it.

I do not see that happening. I think it is impossible to overstate the degree to which the petty, narcissistic type is naturally equipped to command the heights of the attention economy. Or social media’s platform’s dynamics that can bend any of us toward petty narcissism and shamelessness.

More people are testing out alternatives like Mastodon, but I do not think Mastodon is the answer. Yes, it’s a decentralized, open-source social media platform, but user migration will likely be slow. Mastodon’s original source code is publicly available, and it’s made up of a loosely interconnected network of DIY servers. I have been in and out of it and I am intrigued by many who have told me it is strikingly positive — one friend noted it is “open, curious, declarative rather than combative, searching for community rather than representing”. I suspect newcomers are not yet sure what tone to adopt, so people are more exploratory, even withholding, in their posts and interactions. And I was also found it revealing that people were more focused on “finding a community” rather than cultivating a following.

Some Mastodon links for you:

*For an interesting view from someone moving from Twitter to Mastodon click here.

*While Mastodon releases features at a regular clip, its nature as an open-source tool means that you can ignore them if you’d like, or add your own. That’s a refreshing shift from closed social networks. Some details from Ernie Smith.

*A n00b’s guide to Mastodon, which is a very detailed look at using Mastodon. Oh, yes. A “n00b” is a player or member of an online game or forum who acts in a generally arrogant and rude manner. You can read the post by clicking here.

*And this piece explains how Mastodon is designed to be “antiviral”. Subtracting the various things that make virality easy on Twitter – single-press retweets, dunk-tweeting (OK quote tweets) – inevitably makes for a quieter network.

And Mastodon will not be an alternative for brands or advertising. It is currently ad-free so many have not even created official accounts on the platform yet, but ads are coming. But Mastodon’s fragmented model prevents users from observing and participating in the wider world of online discourse. Instead of one central network on which all users interact, it consists of myriad servers housing specific communities. For brands, which need a way of connecting meaningfully with a multitude of diverse users, the platform has its shortcomings. Discoverability is limited. Since users are siloed into a single server, their posts will largely be seen only by other members of that server. So brands will have a much harder time reaching consumers who aren’t in or close to their direct line of sight—a fragmentation that could seriously impact marketers’ presence on the platform.

Twitter’s implosion notwithstanding, interactions on the internet are increasingly siloed into micro-communities, or enclosed spaces with fewer but more engaged members. Various Substack writers I subscribe to have experimented with the platform’s new “Chats” feature in recent days to directly communicate with readers. It’s a pretty straightforward function. Most “Chats”, however, are initiated and moderated by the writer, which can make it hard for conversations among readers to naturally sprout up.

But before I close out this post, a few notes on what we’ll miss about Twitter assuming the bird does fly away.

One of the most obvious losses would just be on current affairs. Twitter can be a fast, dependable way to learn about unfolding political situations. And deeper, it raises awareness about economic, social and political issues across the globe of which you may not know a thing.

Worse, many minority groups across the globe have noted Twitter’s demise would kill a sense of community for many groups that have no other venue.

My guess is that Twitter’s potential death spiral will coincide with a major regional/national/global crisis. For better or worse, Twitter is a crucial disaster communications tool, and we don’t have a replacement for it. Twitter has been a vital source of information, networking, guidance, real-time updates, community mutual aid, and more during hurricanes, wildfires, wars, outbreaks, terrorist attacks, mass shootings, etc., etc. This is something that cannot be replaced by any existing platforms.

More so, if Twitter suddenly stops working or if huge swaths of the population can’t access it during a crisis, the result will almost certainly be preventable suffering and death. To Musk Twitter is a mere playground, not realizing it is as vital infrastructure.

And I could cite hundreds of examples, especially the use of Twitter for crisis-and-disaster-and-communication management. Here is just one that shows the significance of Twitter as a communications tool during Hurricane Harvey.

As that study shows, Twitter has been identified by some researchers as the “most useful social media tool” for communicating during disasters. Other platforms play a role, but Twitter is the central hub for journalists, government, citizens, witnesses, survivors, and first responders. One of the reasons Twitter is such an important communications tool during disasters is that the nature of crises often makes it hard for traditional media to reach the public and the disaster scene. Twitter is often the first and only source of info about unfolding crises. And the design of Twitter is also uniquely conducive for use during crises. Hashtags, for example, become crucial navigational tools to find relevant, up-to-date information and advisories in one central place without having to lose valuable time searching multiple websites.

In another example, close to my heart, the literal and writing communities seem incredibly nonplussed. Many express reluctance and weariness about making a change, seeing Twitter as an excellent venue to dissect prevalent social issues and see and share writing, film and other multimedia. Twitter became a refuge for the relative ease to connect with your peers, share your interests, share your work – with the result editors’ tweets often solicited material. And budding writers used it to find peers to review their work.

Plus new or indie authors often used Twitter to promote their work, eliminating the need for a publicist. And the number of informal writing groups has proliferated. My favourites are the resource groups for writer-parents. An online presence has always been vital and necessary as creative writers who are consumed by the demands of child-rearing may not always be physically present at salons or meetups.

And I suppose at its most pure Twitter allows users to discover stories regarding not just the day’s biggest news and events, but to follow people or companies that post content they enjoy consuming, or simply communicate with friends.

We know all the issues about social media. They have been drummed into our brains for years:

1. Many critics have focused on how social media platforms harvest user data, on how that data feeds into micro-targeted marketing, and on the underlying business model that makes these practices profitable.

2. Others have drawn attention to how social media companies have designed their platforms to generate compulsive engagement, noxiously exploiting how users are drawn to engage more with emotionally loaded and provocative material.

3. Another thread of criticism has targeted the scale of these platforms and their consequent inability to exercise editorial discretion over propaganda and misinformation, while some have noted that propaganda today works not by restricting information but by flooding the field with content, thus sowing confusion and generating epistemic apathy and despair.

I suppose in an ideal world, our social institutions temper our myopic, narrowly self-serving reflexes. That has been the script for most of human history. Society’s taboos, customs, and institutional arrangements, such as family, marriage, capitalism, and democracy, have discouraged impulsiveness in favor of long-term commitment or investment.

But today social media … via those 3 points above … has done much to stick the real world in our face, especially in the U.S.: a national political culture more divided and dysfunctional than any in living memory. All but gone are centrist statesmen capable of bipartisan compromise. A democracy once capable of ambitious, historic ventures can barely keep government (or society) functioning.

And it isn’t that social technology has all of a sudden become weird; technology has always been weird. In fact, in a very deep sense, that’s what technology does – by both increasing and decreasing human capabilities. It changes the fundamental shape of human life. Noah Smith, a technologist who runs a very succesful Substack, said it best earlier this year:

Consider if you could watch an average American human being go about their day in 2022. Much of their time would be spent silently staring into one of two smallish glowing screens — one on their desk or lap, the other in their pocket or bag — and typing on the screen or a connected keyboard.

Now consider going back and shadowing an average American in the 1980s. They’d still spend some of their time watching a screen, but this time it wouldn’t be an interactive one — just something that showed them pictures. At other times they’d be writing on pieces of paper, typing on typewriters, or talking to the people in their close proximity. Some would do manual jobs in construction or manufacturing. But go back even further, to 1900.

Now, the average person would spend a great deal of their time doing menial or manual labor, either housework or in a factory or farm. And some significant amount would be spent in religious observance. The basic experience of human life — what we spend our time doing from day to day — has changed utterly, several times, as technology has progressed.

Elon’s failure with Twitter is not new. A powerful entity or person collapsing under the weight of their own success is not a novel concept. The Ancient Greeks had a word for it: hubris, an excessive confidence in defiance of the gods. For us, it means excessive confidence preceding downfall. Which more or less equates to the same thing, because for the Greeks, defying the gods almost always led to death.

A more recent version of this ancient story that fits our tech-obsessed moment is Frankenstein. Inebriated on his own brilliance, Dr. Frankenstein tries to defy the natural order and create life. In doing so, he makes something too hideous to contain, and that’s his doom. His last words in the novel are an instruction to “avoid ambition.”

More recently, FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried believed he could defy the laws of economics and borrow against large sums of a fake currency he made up. Essentially, he re-invented a foundation of quicksand. And now comes his fall.

The inevitable collapse of the powerful is a good thing, and I’m glad we live in a universe that embraces this as a governing principle. Absolute power and wealth concentration are incompatible with the innovation that characterizes humanity’s upward movement. Yes, the crashing to Earth will cause collateral damage, but it’s a pure creative destruction.

But what have we learned in all of this Twitter nonsense? We leaned that we do not really have “social media”. What we do have, and sometimes enjoy, are a series of communication networks interested in providing a paltry simulacrum of sociality. But the payment is behavior modification and profit maximization.

And all of us get sucked in (I certainly do), desperate sometimes to concoct a mildly clever bon mot, a thought to blow away the Twitterverse.

I know that social media technology has transformed politics and society irrevocably, in a dystopian way, that we are only now slowly grasping. Our civil institutions were founded upon an assumption that people would be able to agree on what reality is, agree on facts, and that they would then make rational, good-faith decisions based on that. They might disagree as to how to interpret those facts or what their political philosophy was, but it was all founded on a shared understanding of reality. And that’s now been dissolved out from under us, and we don’t have a mechanism to address that problem.

There is no clear solution, no simple way forward — not when we understand that digital forms of organizing human communication are also reordering human consciousness and communities, that we are in the midst of a broad and profound social transformation. We are like Angelus Novus, in the 1920 artwork of that name by Swiss-German artist Paul Klee. Walter Benjamin famously described it in the essay “On the Concept of History” in words befitting our angst at social media’s relentless, disordering effects. Like the angel, we perceive the chain of events as “one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet.”

The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.

Walter Ong made much of print’s sense of finality, which places a crucial limit on its ability to capture our minds. “Writing moves words from the sound world to a world of visual space,” he wrote. “But print locks words into position in this space” and “encourages a sense of closure, a sense that what is found in a text has been finalized, has reached a state of completion.”

Here too, digital media appears to return us to the flux of orality, but with a twist. It is not an option, as many today counsel, simply to leave the agora or the assembly and retreat into our private spheres. The marketplace and the assembly hall now surround us, and spill out indefinitely into the future with no prospect of closure. Thanks to the ubiquity of the digital apparatus, we are no longer able fully to step out of the chaotic and contentious flux. Controversies, debates, and crises do not so much resolve as cascade indefinitely. Wherever we go, we cannot escape the storm.