And given it’s a cross-media consortium, how many of these stories will actually “land” with the public and how many will get lost in the deluge. What’s really going to happen with all of this stuff?

26 October 2021 (Paris, France) – There’s so much reporting out there from the consortium of news outlets on “The Facebook Papers” that I don’t really know what to do or where to start. As I noted last week, this “teaming up” by such a large consortium of media (CNN, the Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, etc., etc.) is unusual. It’s not often that major news organizations coordinate to sift through a large trove of leaked company documents and agree not to publish stories about them until a certain date.

But in the world of news related to Facebook, these are extraordinary times. Something similar happened in 2016 when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) published financial leaks in an investigation called the Panama Papers, uncovering details of the global elite’s tax havens, and in 2013 after ex–National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden released top-secret documents, kicking off a storm of coverage in global newspapers about how the U.S. and other governments spy on citizens and organizations.

Over at Protocol they’ve collected a running list of stories published and I count 65 pieces (as of Tuesday evening), many of them thousands of words long. According to Casey Newton and Kara Swisher, there are like six week’s worth of stories like this coming.

I’ve been fortunate to see a few of the documents as a member fo the ICIJ, and I’ve chatted with numerous journalists working through the huge set of internal Facebook documents. There is so much more information in these documents than a single week’s news blitz could capture. For those of you interested, two sources do a great job combining and contextualizing the broad focus of some of the documents and you can find them here and here.

The documents are reasonably technical and scanning through them – even if the content isn’t perfect for a story – is very helpful for understanding Facebook’s culture, workflows, and general bureaucracy. No amount of leaked documents will capture every element of Facebook – “The Company” and “Its Influence”. But it appears that sifting through this data set has given reporters – even those who’ve spent years honed in on Facebook’s nuances – a better understanding of the behemoth.

One of the problems of reporting on big companies that have technical inner-workings and large bureaucracies is that it’s hard to get an immersive, representative view of the way things work. “The Facebook Papers” aren’t perfect but it sounds like they’re helpful and that might pay dividends in the way the company is covered down the line by journalists who’ve viewed them.

It’s also why I think this document set ought to be made publicly accessible and searchable. The Protocol site I noted above is a start – an easy to use, dedicated aggregator.

Many have noted there are very few screenshots or slides floating around. Yes, the stories are a tremendous collective feat of synthesis/analysis/reporting but it’s still a bit strange a large number of stories show no primary source documents (one major exception: Alex Kantrowitz has a Twitter thread with many screenshots of the documents).

I imagine most of this is due to the fact that news organizations only recently received the files and all were essentially on a tight, competitive deadline. I’m certain there are outstanding issues of privacy and name redaction, etc. to consider. Most media now use a very sophisticated Python-based toolkit for redaction and data extraction.

It will be important that the public see the source material. Researchers, and not just those well-connected enough to be granted access, should be able to parse these materials with their own expertise and frames of reference. As I noted above, simply spending time in the files will likely grant the media troops some helpful perspective on the company’s bureaucracies/processes. For the press, documents are always a helpful way to bolster the stories’ credibility. But, just as important, publishing the Facebook materials responsibly is ideologically consistent for news outlets. For years journalists have argued for greater transparency from companies like Facebook.

Many of my colleagues are recommending Ellen Cushing’s piece, ‘How Facebook Failed The World’ over at The Atlantic. If there is one insight to privilege in the rash of stories this week, it is that the negative impacts of the platform outside the United States are the most concerning and damaging and still, somehow, under-reported. If there’s one thing that Facebook’s senior leadership should be held accountable for (and that should keep senior leadership up at night) it should be what’s described in these global-focused stories. I particularly appreciated Cushing’s framing here:

But these documents show that the Facebook we have in the United States is actually the platform at its best. It’s the version made by people who speak our language and understand our customs, who take our civic problems seriously because those problems are theirs too. It’s the version that exists on a free internet, under a relatively stable government, in a wealthy democracy. It’s also the version to which Facebook dedicates the most moderation resources. Elsewhere, the documents show, things are different. In the most vulnerable parts of the world—places with limited internet access, where smaller user numbers mean bad actors have undue influence—the trade-offs and mistakes that Facebook makes can have deadly consequences.

I would also suggest this Wall Street Journal piece on Facebook fomenting religious hatred in India. The results are what we’ve long assumed/known and yet still somehow still worse.

Yes, a lot of stuff shared. And yet … what’s going to come of it?

The “hopeful brigade” says the revelations will kick off genuine, creative, semi-partisan regulatory conversations about the platform. Or perhaps they will force mass resignations inside the company that lead to some kinds of reforms to retain talent. Perhaps something truly wild happens that creates legal trouble/liability for the company’s executive leadership.

The “dismal brigade” (I’m in there) thinks that all of the revelations from the “Facebook Papers” merely confirm what a lot of activists, journalists and lawmakers knew or suspected … and lawmakers never react proportionally.

Plus the irony. There’s simply an information overload from too many stories at once and this cycle is eventually lost to the very algorithmically driven, fast-churn news cycles that Facebook helped create. I am curious and unsure, for example, about what happens to any regulatory Facebook momentum if the former president decides to launch a political campaign in earnest soonish. He used Facebook to the max in 2020 and all of his aides say he is champing at the bit to get back in.

If the regulatory reformers get their wish, there’s a whole host of thorny questions and contentious debates waiting in the “How Do You Fix Facebook” category. There are all kinds of interesting ideas and lots of focus on regulating Facebook’s algorithms.

Hoo, boy. My regular readers know I’m not in favor. Potential platform “fixes” have every potential to jack up the internet in unforeseen ways. Just two weeks ago Democrats proposed a new Section 230 “reform” bill that would actually function more like a 230 “repeal”, not reform, because it opens the floodgates for frivolous lawsuits claiming algorithmically amplified user content caused harm (a wildly broad category for an enormous amount of content). This is merely one very small example to highlight that we’re in complicated and still treacherous territory even if/when there’s consensus to “fix Facebook”.

Of course you can’t really “fix Facebook” – certainly not in any tidy/quick way. You can certainly might make it safer. And if this week’s reporting has shown anything, it’s that even people inside the company who were hired to study and provide guidance on ways to make the platform safer have found it nearly impossible to push for change at the necessary scale, thanks to executive leadership.

And in his recent post Max Read nails it :

To consider…Facebook only in terms of a value proposition — net good or net bad for humanity — is to miss that it shapes the world as much as the world shapes it.” This sounds simple but it’s actually a dizzying idea that’s almost impossible to unpack without living outside of our current history. Big Tech has largely succeeded in re-imagining and re-making parts of our culture, government (Republican politics is legitimately like 51 percent professional shitposting), and economy.

You can’t necessarily change the ways all this shit has changed us or the ways it will continue to distribute/re-distribute money, power, influence, culture, and information. You can probably find ways to ameliorate the inequalities some but “fix” is an impoverished word when it comes to Facebook. Fix? What, exactly? And how, exactly? Can we even decide and agree on what to fix and how? You tell me.

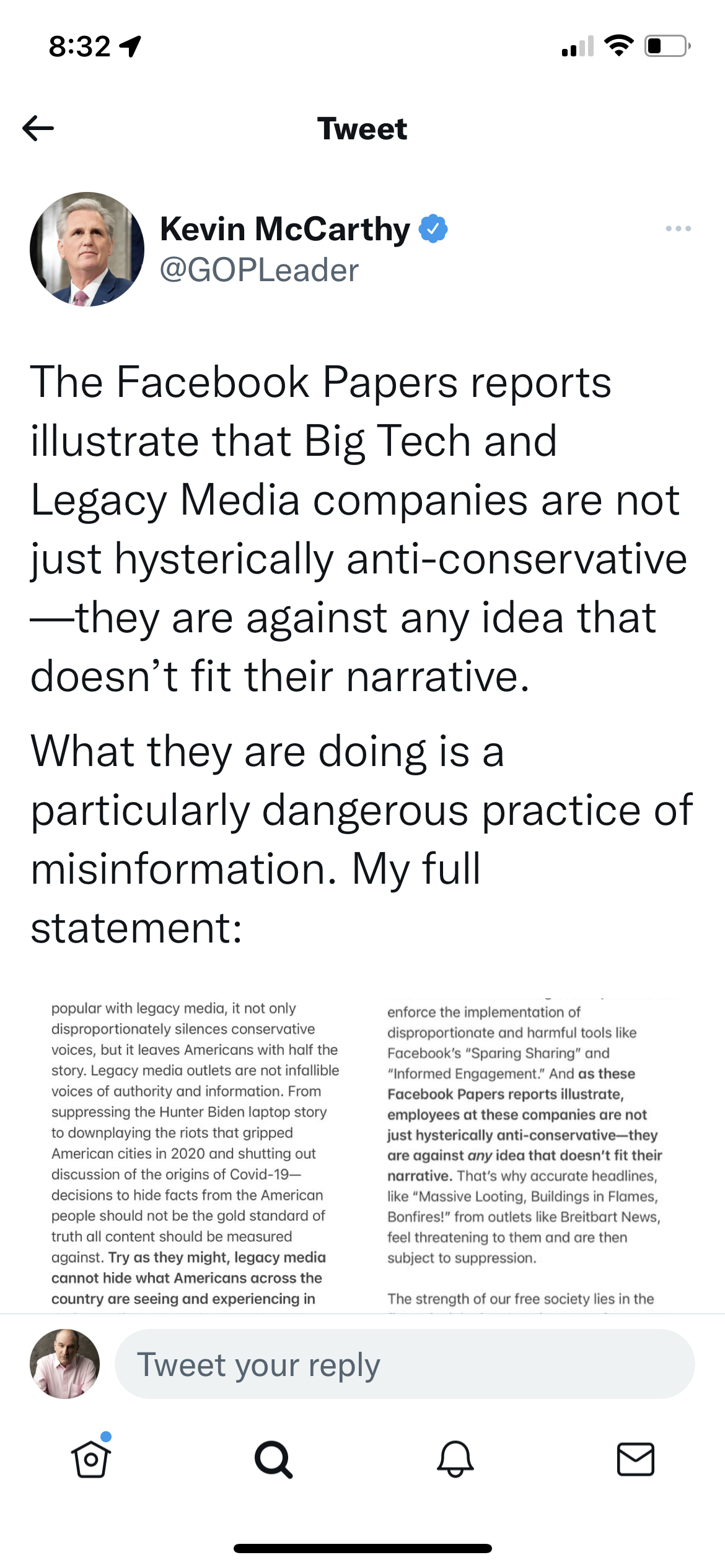

But before you do, here’s what the Republican leader in the House said in response to the Facebook Papers:

He’s basically ignoring the real content and making up his own false content and takeaways to justify his politics. The classic Republican move. How do you “fix” that?

BOTTOM LINE: Yeah, Facebook is too big. But people will tune out due to over-saturation. Any “fixes” that could come from any momentum are going to be extremely treacherous, too. We’re too late. We’ve caught up to what Facebook hath wrought (2012-2020) and Mark Zuckerberg and executive leadership seem to regard that version of Facebook as almost an outdated node of the company. They’ve got a new digital realm to colonize: The Metaverse!

As I noted yesterday: “platformization”. It’s going to be hard to untangle Facebook and all the other platforms from, well, everything else … including the way these platforms have changed us, the way that the architecture and nature of these platforms act on us and how we, even reluctantly or unwittingly, absorb some of their characteristics. That reckoning will be particularly painful and I’m not sure we fully possess the language or countervailing institutions or historical hindsight to start that work in earnest right now.