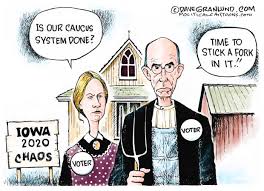

5 February 2020 (Paris, France) – As the news of the chaos that upended the Democrats’ Iowa caucus rolled out and I saw references to “Shadow” and “ACRONYM” my immediate thought was: “Oh, my God: the Democratic National Committee hired the same team that was working on the new “Iron Man” spinoff!” Yes, once again the U.S. has shown itself to be a paragon of well-functioning democracy. A symbol to the world. Time to adopt rock-paper-scissors as the official, more reliable method for selecting the “leader” of the free world.

But as reams and reams and reams of analysis has noted, it bears all the hallmarks of a collision between poorly vetted computer code, inadequately trained volunteers and party officials who waved off warnings from outside experts. A completely untested system. Security experts had warned (and warned) Iowa officials that using an untested unaudited app on unsecured phones was a terrible way to count votes. They didn’t listen. But at least there are paper counts to fall back on. As Jeremy Epstein said (he is a voting security expert who is the vice chairman of the Association for Computing Machinery’s U.S. Technology Policy Committee, and he seemed to be popping up on every news show last night):

Writing reliable software is very hard, and I’d say this is a case in point. Macy’s doesn’t roll out a new cash register the day before Black Friday — you test it out in a limited market and figure out the problems without the pressure.

And it’s not like we haven’t been here before. Remember these?

1. Orca, Mitt Romney’s Election Day app, which was supposed to help volunteers get voters to the polls, but instead was overwhelmed by traffic and stopped working, leaving thousands of fuming voters without rides.

2. In 2008 to Barack Obama’s app, dubbed Houdini, which also crashed on Election Day.

3. It happened to HealthCare.gov – the website that was launched to help people find coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but that failed so badly, it took a team of people from Silicon Valley who quickly and voluntarily left their much cushier jobs and worked seven-day weeks for months to fix it.

There’s a lot to say about the technology – who made it, how it failed, and why it matters – but the first thing to say is that the actual voting process, however flawed the Iowa caucuses may be, went off just fine. People voted; their votes were counted and written down on paper “preference cards,” and those cards were collected for safekeeping in the event of the need for a recount.

But if you do not want to wade through the tsunami of info out there (query: can you wade through a tsunami?) I suggest you just read the Vice investigation, which found that the two-factor authentication was screwed up on the app (which the DNC spent the grand total of $60,000 to build), the app didn’t work on a number of phones (everybody thought it was just a web app with some OS-friendly clothes), it was untested, etc., etc.

And, of course, there is the real dark side. Because misinformation loves a vacuum. When Democratic officials said that results would be delayed while they were vetted, Trump associates pounced, asserting that the contest must have been rigged. It was part of a sustained effort on the right to delegitimize the contest’s winner, which also included a viral article from Judicial Watch falsely suggesting that Iowa had a voter fraud problem. It now seems very clear that legitimacy will be a primary battleground of the 2020 election. Partisans of the losing candidate will be quick to declare widespread fraud on the slightest of evidence, and partisans of the winning candidate will be called to marshal incontrovertible evidence of their victory.

It still baffles me so many Americans still believe they live in a democracy, a Republic and still believe there will be/are full and fair elections. They are blinded and simply do not see what is coming this fall.

But if you really want to understand what happened with Shadow and the failure of the Iowa Caucus app you have to understand how electoral campaign tech work is done and how it funded. So I will turn to Evan Henshaw-Plath. Evan was Twitter’s first employee and I met him years ago at Black Hat. He is a self-described “anarchist, hacker, troublemaker” and has been working on the decentralized web. He has been instrumental in helping me understand our transition from an electric-to-digital-to-networked age: all the “tubes and wires and ether” that created our distributed information and communication technology infrastructure.

Last night he distributed a humdinger of a piece. Take it away, Evan. Oh, and I have a few concluding thoughts in a Postscript after Ian’s monograph:

If you want to understand what happened with Shadow and the failure of the Iowa Caucus app you have to understand how electoral campaign tech work is done and funded. Let me tell you a story to make sense of it.

The caucus app is firebase / react app built by one senior engineer who’s not done mobile apps and a bunch of folks who were very recent code academy graduates who as of a couple months ago worked as a prep cook for Starbucks and receptionist at Regus.

They messed up, but here’s the thing, shadow is a company which came out of of the collapse of another electoral tech company, Groundbase ( http://getgroundgame.com ) which has some well known folks in the campaign tech space.

I know about this space because I tried to do my own project, http://affinity.works , in a similar space, and through that work got involved http://opensupporter.org standards process to make data sync between various systems.

What shadow, groundbase before it, and many of the rest of us like affinity and groundwork (similar name I know) all want to do is solve the problems which come up in progressive campaigns. We’re trying to create tools for the organizers.

Shadow made some tools which look useful, their messaging app is similar to hustle and http://getthru.io . Their lightrail app http://shadowinc.io/lightrail is something people really need.

Think of it as a Yahoo Pipes/Zapier but for the specific api’s that we use in progressive campaigning from NGP/VAN, ActionKit, and ActionNetwork.

Lightrail is solving the problem that most people on campaign tech teams have. Mostly the job is wiring up various services, moving the data in to the right spot so the digital and filed teams can be effective.

To understand why shadow exists and how they failed to provide the tools the Iowa Democratic Party needed we need to know how this space works.

The fundamental problem is we’ve got a very broken way we fund campaign tech on the democratic side of the isle in the US. There is tons of money in politics but it doesn’t get used in the way which builds anything sustainable. Here are some reasons why.

Campaigns have a few primary motivators. First is getting votes, you want to win elections, if you’d don’t win, you don’t get to keep playing. To win, you need money, and you need to stay compliant with FEC rules. Break the rules, people don’t vote for you, unless you’re Trump.,

Run out of money and your campaign is done. Just look at the reason given for most democratic presidential candidates dropping out this cycle. They quit when they can’t raise more money.

So, we have tons of money, and money for campaign tech, but it’s very focused on raisin money, keeping track of money, and legal compliance. NGP/Van is very very good at meeting these needs, they’re the centralized company which most democratic politicians use for their campaigns

It’s tech around money / accounting is great, it’s tech around walk lists and mobilizations is ok, it’s tech around movement building is terrible.

Some org’s like ActBlue focus on the one very lucrative part of the stack, collecting small dollar payments with compliance.

ActBlue does that one thing really really well, it’s transformed political campaigns, but doesn’t provide a funding channel for all the other tools we need.

Non-candidate groups often use ActionKit if they’re bigger or ActionNetwork if they’re smaller, or even NationBuilder. The latter became persona-non-grata after working to get Trump elected. MoveOn funded the creation of ActionKit, and the AFL-CIO did it for ActionNetwork.

Thousands of groups use ActionNetwork, but it’s barely viable as a sustainable entity despite providing a very important service. ActionKit was recently rolled in to NGP/VAN because it wasn’t sustainable as an independent entity.

The space is dominated by decision makers who are stuck on a very short term decision making cycle. Structurally there is no space for long term investment, despite everybody stating that this would be good.

In normal tech circles we’d have a bunch of free software libraries and tools we build on together, but the campaign tech space doesn’t have this because decision makers fear our tools will be taken and used by the other side.

This is despite the fact that ‘they’ use totally different standards, tech, and structure of work. Ours works better than theirs, but it’s not saying much.

In the wake of the 2016 election there was a lot of energy around funding better tools. We had folks like @raffi go over to work at the DNC. We had Higher Ground Labs promise money in to the space, they funded Shadow, and many other projects.

Unfortunately they funded it using a startup / incubator model. Giving startup funds to many projects in a cohort and helping them get to an MVP and pitch founders for more money.

After the initial infusion, there was no more money to be had. These projects all failed when they ran out of money. There was no budget to fund development between cycles. The decision makers know nothing about how technology, or its development works.

Most of us gave up on building campaign tech. Thousands of other dedicated technologists who are organized through http://progcode.org and http://ragtag.org are struggling but unsustainable.

Campaign networks like indivisible, sister district, swing left, all use extensive tech but don’t have budgets to fund its development.

I myself am now building @planetaryinc, @slaby is at @harmonylabs, @harper is bouncing around the world being his fabulous self having left the Obama campaign to do a payments startup. @elipariser is doing @civic_signals to fix social media platforms.

The decision makers refuse to use free software, alienating the progcoders/ragtag communities. They also refuse to fund projects between cycles to build reusable platforms.

So what do projects like http://affinity.works and shadow do when they want to keep the lights on? They take one off campaign jobs. Affinity built tools for the Yes on 1631 carbon tax campaign in Washington, and Shadow built a caucus tool for state democrats.

This was a quick tool which was put together without sufficient funding. See, building tech is expensive. We can see from the budgets that the Iowa Democratic Party only paid $60k to shadow, and the Nevada party paid $58k.

It might feel like a lot, but it really isn’t given how much this stuff costs to build. It’s why the app wasn’t well tested or scaled well. The team was a few enthusiastic recent code school grads and one experienced engineer. This was their side project they built to get funding

There is no way they could succeed. The problem is structural, the way we’re funding campaign tech is wrong. We need it to be based on open source technology, we need a community of companies, parties, and third party groups funding it. It needs to have funding between cycles.

There needs to be much more money in order to sustain things. The Obama and Clinton campaigns spent tens (maybe hundreds) of millions of dollars on tech but it was building tech which was mostly thrown away.

We’ve got a few vendors that last between cycles, but all the techies who work on campaigns go back to normal startups.

A couple days after Obama was re-elected the political staffers walked in to the tech floor of the Obama campaign HQ and wondered where everyone was. They’d all be laid off, @harper had found them jobs in industry & everybody faded back in to tech companies.

From a staff of hundreds, a handful went to work at the White House or OFA, but for the most part that knowledge was all lost.

We’re treating our campaign tech teams like we treat the field organizers, and it’s not working. It doesn’t work for the field teams either, that’s why they unionized.

If we want to prevent disasters like the Iowa caucus app or the failure to do effective social media campaigning in 2016, we need to change the way we fund, build, and employ the campaign workers, techies included.

What should have been done? The app shouldn’t have been built. This didn’t require an app. There are lots of ways to submit and verify vote counts without needing a custom app. At least they kept the paper backup.

The sexy desire to have an app is something we should avoid.

Focus on the problem, not the solution of an app which sounds cool. The Iowa Democratic Party shouldn’t have asked for an app. The media shouldn’t have hailed it as futuristic, we shouldn’t demand immediate electoral results, and shadow shouldn’t have tried to build it.

You could have done a system with google docs and having multiple people send in pictures of the tallies at each polling place. Or any number of other solutions which requires less software. There’s a whole field of lean startups dedicated to solving the problem with less code.

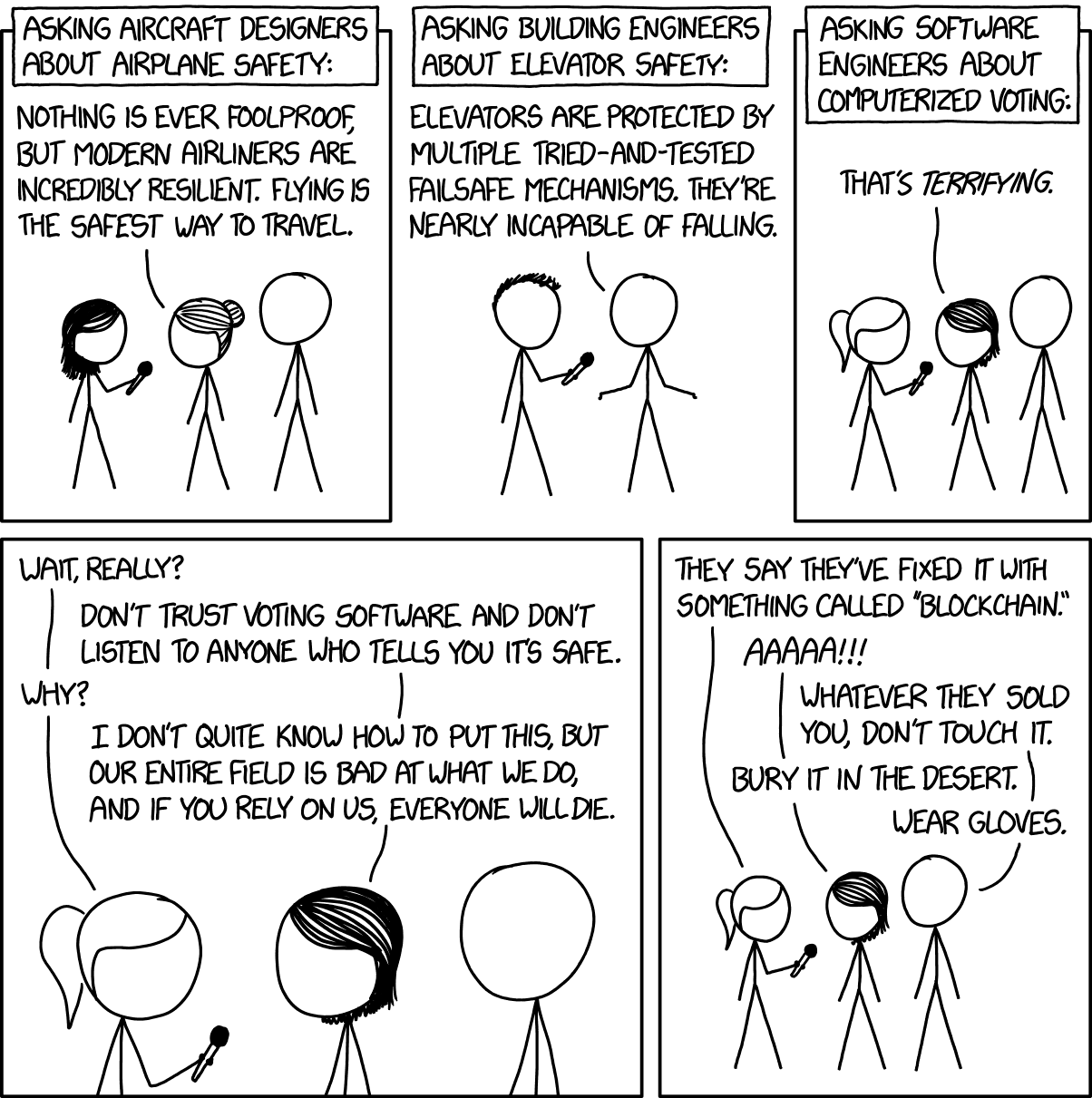

Folks like @mattblaze and @EdFelten, and many others have documented why digital voting systems are a broken concept. There is is no way to do it securely. Use paper, use people, verify, audit, make it transparent to all the campaigns. Force the media to wait for results.

POSTSCRIPT

Not to beat a dead horse but we are living in an era of what political scientists describe as “strong partisanship and weak parties” — or, alternatively, as “negative partisanship.” The electorate is polarized into opposing camps, but their emotional impetus is driven by hostility to the other party rather than trust in their own.

The Republican Party’s solution to this predicament? Fashion itself as a cult of personality devoted to Donald Trump.

The Democratic Party’s solution to this predicament? A series of technocratic fixes intended to increase its own legitimacy. But the Iowa caucus is the latest indication that the effort is collapsing.

One of the oddities of the 2016 presidential race is that, while the Republican Party was taken over by an outsider initially viewed as dangerous and unacceptable by its party elite, it was the Democratic Party that concluded its nominating process had failed. Supporters of Bernie Sanders repeatedly applied his trademark phrase — “rigged” — to explain a primary they clearly lost. Complaints about “rigging” began with an agonizingly narrow Sanders defeat to Clinton in the Iowa caucus four years before. They continued throughout the contest, with every routine snafu — in Nevada, New York, and the possibility that party superdelegates would provide Hillary Clinton the winning margin — held up as more evidence of the conspiracy.

And now the Democrats face extinction – of their own accord. The party instituted a number of changes intended to inoculate itself against accusations of rigging. In Iowa, the Democratic caucus instituted new rules, “mandated by the DNC as part of a package of changes sought by Bernie Sanders” and “designed to make the caucus system more transparent.” The new rules required reporting several different sets of numbers from every precinct. And the incorporation of complex technology.

As Jonathan Chait noted in his blog last night:

Anybody who has witnessed or participated in a grassroots progressive organization – especially one in the digital age – has seen this intricate, rules-based method democracy in action. Monty Python lampooned the tendency in Holy Grail. (“We’re an anarcho-syndicalist commune,” a peasant explains to the impatient King Arthur. “We take it in turns to act as a sort of executive officer for the week, but all the decisions of that officer have to be ratified at a special biweekly meeting by a simple majority in the case of purely internal affairs, but by a two-thirds majority in the case of more major …”).

Well, watch the whole clip. It is marvellous:

As Jonathan notes, in the end, the Iowa Democratic caucus will probably report accurate results.

But the corrosive damage to the legitimacy of the system will remain. What ought to terrify Democrats is that the process is only beginning. It will be, by design, more elongated than their process in 2016, but last night Democrat party leaders acknowledged they will have less and less influence over its outcome. So far, the attempts the party has made to stave off challenges to its legitimacy have only exacerbated them.