15 July 2019 (Chania, Crete) – Last Friday it was revealed the U.S. Federal Trade Commission voted to approve an approximately $5bn settlement with Facebook over privacy violations. And, as expected, politicians and pundits on Twitter over the weekend reacted viciously:

– “A drop in the bucket”

– “A Christmas present five months early”

– “So meaningless”

– “A victory for Facebook”

– “An embarrassing joke.”

– “Chump change”

– “A thumbs down for consumers”

As I noted in a newsletter to clients over the weekend, the size of this fine is, of course, laughable in the context of FB generating an estimated $25bn of EBIT this year and $30bn in 2020 and net cash of c. $70bn on its balance sheet. A fine of around 2 1/2 months’ of operating cash flow is an encouragement, not a deterrent, to keep stealing and monetizing data from FB and Instagram users. But a bit lost in the anger over the amount of the fine was a quote from several media reports by “a person familiar with the deal” that the settlement will include “proposals to change how Facebook handles and stores user data and what customers know about those practices” as well as “making the company more transparent to the FTC”. We need to see, of course.

And as one of my regular readers pointed out, in theory, it could have been worse. Like 1,000 times worse. Literally. He said:

In 2011 the FTC and Facebook hammered out a 20-year consent decree to resolve a series of allegations that the social media giant violated Section 5 of the FTC Act, which bars unfair or deceptive conduct. For example, the FTC in 2011 said Facebook failed to reveal that third-party apps could access nearly all of users’ personal data, and also falsely promised users that it would not share their personal information with advertisers, but did so nonetheless. Without admitting wrongdoing, Facebook at the time agreed to mend its ways and never again do anything like, say, “misrepresent in any manner, expressly or by implication, the extent to which it maintains the privacy or security of covered information.”

But then, Facebook in 2018 admitted that as many as 87 million users had their personal information improperly shared with data firm Cambridge Analytica. Researcher Aleksandr Kogan allegedly created an app, “This Is Your Digital Life,” designed to collect data surreptitiously from people who took the quiz as well as their friends—information which was later sold and allegedly used by the Trump campaign, among others, to target voters.

Look at the numbers. The penalty for violating a final FTC order is $40,000 per violation per day. So … 87 million times $40,000 a day is $3,480,000,000,000. Per day.

Looking at the FTC “rulebook” on deciding how to calculate the penalty for violating an order, the FTC says it considers:

(1) harm to the public

(2) benefit to the violator

(3) good or bad faith of the violator

(4) the violator’s ability to pay

(5) deterrence of future violations by this violator and others

(6) vindication of the FTC’s authority.

So how (exactly) does that add up to a $5 billion fine for Facebook? It’s hard to say, and so far the FTC ain’t saying. But everybody agrees, Facebook has the ability to pay more. Moreover, Facebook’s stock rose 1.8% on Friday after news broke of the deal, suggesting that the market agreed that the company came out on top.

So why let the company off the hook for $5 billion? Well, another of my reader’s has the answer, he says. It is because the FTC case against Facebook might not be as open-and-shut as it might appear. His firm was tracking the 2011 FTC settlement (his firm represents another social media company) and he said few people paid attention to the 2011 dissent filed by then-FTC commissioner Thomas Rosch – which flagged a potential loophole in the 2011 agreement. Quoting from the dissent:

“While I hope that the majority is correct in their assertion that the consent order covers the deceptive practices of Facebook as well as the applications (‘apps’) that run on the Facebook platform, it is not clear to me that it does. In particular, I am concerned that the order may not unequivocally cover all representations made in the Facebook environment (while a user is ‘on Facebook’) relating to the deceptive information sharing practices of apps about which Facebook knows or should know.”

You can be damn sure Facebook’s legal team (Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher) was vigorously arguing that their client did not violate the order, and that the misconduct by Cambridge Analytica fell outside the scope of the consent decree. So just maybe $5 billion was actually a good settlement for the FTC.

BUT … nobody knows the actual terms of the deal, just the reported dollar figure. And as I pointed out earlier in this post, the media has been quoting “somebody in the know” that says there will be injunctive relief and non-monetary provisions to deter future wrongdoing. Corporate monitor perhaps? Audits of quarterly reports? We await with bated breath.

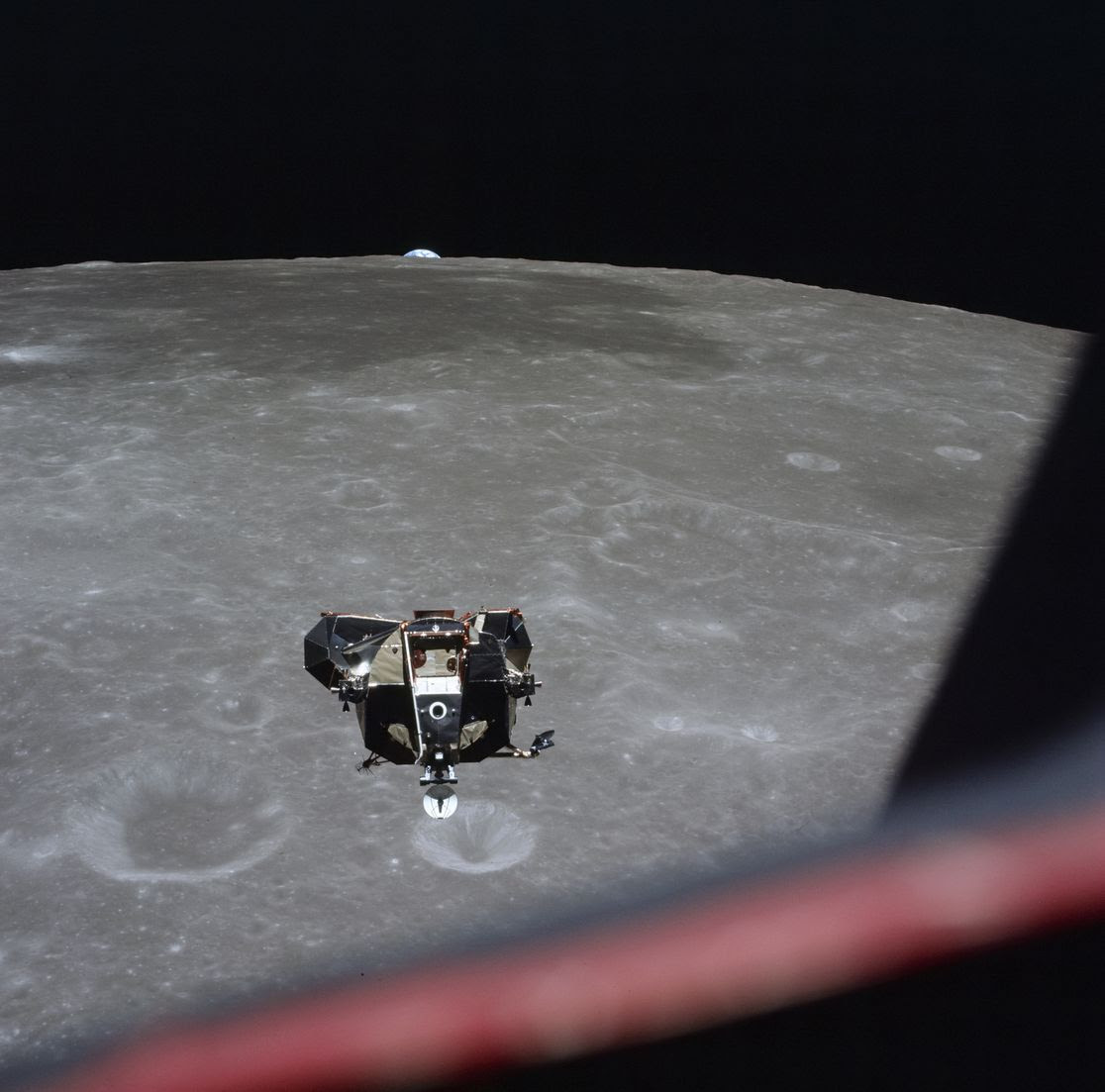

On July 21, 1969, the lunar module approaches the command module, with Earth visible behind the moon. [Photo by Michael Collins, pilot of the command module, from the NASA Apollo photo archive]. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC. Armstrong became the first person to step onto the lunar surface six hours later on July 21 at 02:56:15 UTC; Aldrin joined him 19 minutes later. They did not stay long.

The Apollo space program was the capstone of an era in which Americans took it for granted that the federal government could and should solve big challenges. It was one of America’s defining moments. Engineering, heros and awe – all in one package.

But not since then has the U.S. tried something as ambitious or as expensive. Yes, Americans still take risks and solve problems, but they don’t look to the federal government to do it. Back then, the federal government, enmeshed in the space race and Cold War, spent twice as much as private business on R&D. Today, business spends three times as much as the federal government. We now equate risk-taking and innovation not with moonshots, but with venture capitalists, pharmaceutical labs and internet entrepreneurs.

Much of this comes from my current read “The Moon” by Oliver Morton. The book ranges through science, history, politics, art, science fiction, speculation and more besides. An account that is not only rich in facts, but leavened with fiction, for the author seems to have read widely in the literature of science fiction to show the interest, ideas, and fantasies people have had about our nearest companion in the solar system. To show how the moon has been perceived by humans over the centuries, he draws on Renaissance paintings, Victorian works, music, Robert Heinlein’s novels, and transcripts of conversations between Apollo astronauts and Mission Control in Houston. Quite frankly it is accessible, informative, and entertaining — first-rate popular science reporting.

It is one of several books I am reading to prepare for the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. And even though I am on my (large) rock in the middle of the Mediterranean, this weekend I’ll be celebrating with mates from the Astrophysics Group of the University of Crete, at Crete’s “pretty-impressive-for-a-small-island” Skinakas Observatory.

It was all ideological. When Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space on April 12, 1961, the newly inaugurated President Kennedy needed a way to reclaim leadership from the Soviet Union. He asked his vice president, Lyndon Johnson, to devise a space program that promised dramatic results, and that the U.S. could do first, according to John Logsdon in his book “Race to the Moon”:

The answer came back: “go to the moon.” On May 25, in a speech before Congress, Kennedy set a goal that before the decade was out, the U.S. would put a man on the moon and bring him home safely.

Kennedy never stopped worrying about the price, first pegged at up to $9 billion for the first five years. He suggested to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that they combine efforts to defray the cost. Khrushchev demurred. Liberals complained that the money could be better spent on anti-poverty programs, conservatives that it should go to defense. Yet for Congress, at least initially, price was no object. The U.S. budget was in rough balance and the Soviet lead in space was viewed as an existential threat.

No one believed this more fervently than Johnson, as Senate majority leader, vice president and then president. In his memo to Kennedy advocating a lunar landing, Johnson wrote: “If we do not make the strong effort now, the time will soon be reached when the margin of control over space and over men’s minds through space accomplishments will have swung so far on the Russian side that we will not be able to catch up, let alone assume leadership.”

Johnson embodied the New Deal ethos that the federal government could, and should, accomplish big things, as it had with the Tennessee Valley Authority and Grand Coulee dam during the Depression, the Manhattan Project during World War II, and the Interstate Highway System starting in the 1950s. Says Roger Launius in his book “Apollo and the Great Society”:

Johnson, a New Dealer, viewed the Great Society as an extension of that, and Apollo as part of the Great Society. The space program would have economic benefits. Huntsville, Alabama and Houston, Texas are space hubs thanks to Johnson’s use of space as a spur to Southern economic development. NASA outsourced much of Apollo’s development to private contractors, which both earned the program support and spread its benefits. Technology developed for the space program spurred advances in computers, miniaturization and software, and found its way into scratch-resistant lenses, heat-reflective emergency blankets and cordless appliances. It inspired thousands to pursue careers in science and technology. Doctorates awarded in engineering and physical sciences tripled from 1960 to 1973.

But then it ended. As the lunar missions wound down in the 1970s, budget deficits and inflation were eating away at the economy. President Nixon, less passionate about space than his predecessors, issued a policy statement in 1970 declaring: “Space expenditures must take their proper place within a rigorous system of national priorities.” Federal R&D declined, priorities shifted: health now accounts for 30% of the total budget, up from 5% in the 1960s. Funding for basic research has been relatively stable, but the development part of R&D collapsed, reflecting the bipartisan view that government resources are best directed to areas where the profit motive doesn’t operate.

And so space travel is increasingly left to profit-driven entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. Yes, Presidents still invoke the spirit of Apollo (President Obama called for an Apollo-scale investment in renewable energy and a “moonshot” to cure cancer; President Trump has said he wants to return to the moon, and then go to Mars).

But as Greg Ip, Science editor for the Wall Street Journal, noted on his blog over the weekend:

These grand visions lack Apollo’s unifying motivation of the Cold War, the clarity of its target, and the New Deal faith in big, ambitious government. The intensifying U.S. rivalry with China is sometimes called a new Cold War, but it’s being waged with private investment such as in 5G telecom networks, not public projects.

Yep. We can solve ‘X’ – provided it is a technical challenge. But you need to throw money at it and manage how it is spent properly. But today more of our problems are social – and you can’t solve social problems that way.