9 June 2019 – The French government has amended Article 33 of the Justice Reform Act to prohibit the use of data analytics on judicial behavior. The new law specifically prohibits:

The identity data of magistrates and members of the judiciary cannot be reused with the purpose or effect of evaluating, analysing, comparing or predicting their actual or alleged professional practices.

This change is in opposition to a number of legal tech companies that are currently analyzing data about current practicing judges to identify trends in behavior. The new law prescribes five years of imprisonment for violators, though it is not entirely clear how this law will be enforced, and many judges fully admit there are numerous ways to get around it. Plus, as many have said “prove to me I arrived at my answer via statistical modeling, and not plain old fashioned research and informed opinion?”

The decision, understandably, rocketed around the U.S. and the UK legal media markets and social media. This technology is already in use in both countries. Several U.S. judges, reacting to the ban, Tweeted they would love to see a statistical analysis of their decisions in order to better monitor their performance.

A good summary of the issue can be found in Artificial Lawyer where you will also find some very good reader comments. A number of U.S. legal media sources have noted the change was reportedly a compromise between judges who wanted their names redacted from opinions when published online, and those who felt the public had a right to them.

That is somewhat correct. But after an extensive legal career in the U.S. and having lived and worked in France on-and-off for 18+ years I can say that really does not capture all of what is going on. You have to understand that the French legal system is rather different from the one in the U.S. and UK. Yes, France has many legal technology vendors that use artificial intelligence for the quantification of legal risk. Many model the judicial decision-making process to present a whole package of decisions that could and would affect a given file. These risk quantification solutions are collaborations between lawyers and mathematicians and there is, in some cases, more than 20 years of research work.

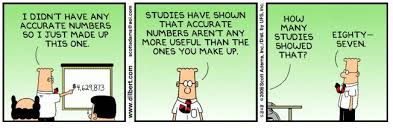

But there is push back because statistics are often seen as rather crude instruments with well-known biases, and, in this case, at least in France, they would give inaccurate views.

I will make a few points. And I though I might seem to be way too expansive when I refer to “the French” I do provide my own experiences, as well as the pro and con views of my French colleagues.

The U.S. love affair with analytical technology

For many French there is a feeling that in the U.S. all discussions on law, politics and culture have been steadily absorbed into the discussion of business. There are “metrics” for phenomena that cannot be metrically measured. Numerical values are assigned to things that cannot be captured by numbers. Economic concepts go rampaging through noneconomic realms: economists are our experts on happiness. Where wisdom once was, quantification will now be. Quantification is the most overwhelming influence upon the contemporary American understanding of … well, everything.

I have certainly written about this before. It is enabled by the U.S. idolatry of data, which has itself been enabled by the almost unimaginable data-generating capabilities of the new technology in all fields. Techno-financial automatism has replaced thoughtful reflection, has taken the place of political decisions. The tech nerds among us make the constant mistake of correlating advancements in technology with moral progress. No. The distinction between knowledge and information is a thing of the past, and there is no greater disgrace than to be a thing of the past.

David Paineau, in his upcoming book on statistical evidence in the law, says knowledge is a stone-age concept, that we’re better off without it. Our preference for eyewitnesses over statistical evidence is nothing but a reflection of our crude prehistoric concern with knowledge.

But to the French this is not about knowledge but about probability. As a long time French legal colleague notes:

Our brain is locked inside its bone case in the dark and it receives impulses that are somewhat prejudiced by genetics towards some form of certainty out of the history of survival. Our whole massive system of working with sensory input is a matter of learning to guess the levels of probability of what we might know. I am not enamoured with these statistical methods.

But there is also an opposite feeling. Another colleague noted:

It is a pity that the government is obscure, because this type of study just banned could have revealed dysfunctions or areas that could have been improved as a result. I know that artificial intelligence and analytics affect an increasing number of sectors and the legal field will not be spared. But I am not in favor of attempts to replace judges with algorithms or “predictive justice” as in the U.S., given all the stories of how it fails and leads to massive injustice.

And said another:

Look, even in France, law firms use companies that promote legal technologies that can analyse millions of court decisions per second, which makes it possible, for example, to assess the probability of success of a litigation action. And these technology companies also build models of judicial behaviour on certain issues or in response to different legal arguments. With such information, law firms optimize their strategies in court.

The present action … the banning of the publication of statistical information on judges’ decisions … was clearly aimed at the legal technology companies that specialize in analysing and predicting the outcome of disputes as I noted above. But it is just one move of many previous efforts to make court decisions less easily accessible to the general public, or to allow greater transparency in the sector. There is this general need for anonymity (or fear) among judges that their decisions may reveal a too large deviation from the expected standards of civil law. That their “human subjectivity” will be revealed. As the Artificial Lawyer article (referenced above) points out:

Judges in France had not reckoned on NLP and machine learning companies taking the public data and using it to model how certain judges behave in relation to particular types of legal matter or argument, or how they compare to other judges. In short, they didn’t like how the pattern of their decisions – now relatively easy to model – were potentially open for all to see.

It is clear that there must be limits to the data that information technology companies can be allowed to collect on individuals. But for critics of this new law, judges’ decisions made public are “public data” and their use should not be restricted in this way. If a legal case is already in the public domain, any person who so wishes should have the right to carry out a statistical analysis of the resulting data in order to answer questions they may have. After all, how can a society dictate how citizens are allowed to use and interpret data if that data has already been made available to the public by a public body such as a court?

“And in the U.S. court system, if you have any information that would help

your opponent, you have to give it to them”

“We’re going to listen to the Americans about running legal systems?!”

Not lost on anybody, especially the French, is the performance of Trump’s authoritarian theater which continues to assault America’s justice system, disintegrating the people and processes that are the foundation of the nation’s administration of justice. Over the weekend I had dinner with a French legal colleague who just returned to Paris after a two-year stint in New York at his firm’s U.S. office. He had the opportunity to attend Legaltech plus a Sedona conference and a few other legal practice workshops. He was amazed no speakers (or even attendees) at any event wanted to talk about Trump and his abuse of the U.S. legal system (“no politics; we are here to sell”). He said all they wanted to talk about was “legal innovation”, legal analytics and all the advanced technologies such as machine learning and natural language processing to clean up, structure, and analyze raw data from millions of case dockets and documents. And when politics and the legal system did come up at a technology conference it was only about:

At a Sedona event he was “highly amused”. Many of the law firms at the event were squawking about the need for “meet & confer” and improving the justice system to make it less adversarial … the same firms he encounters out in the “real world” still making it a blood sport.

So for him:

Oh, the hypocrisy. Any American criticism about the French ban on judicial analytics I dismiss. They are telling us how to run a legal system?!

But I tried to turn him around to see the benefits of such judicial analytics, that it could be helpful to see a judge’s possible mediocrity. Perhaps even make it possible to identify potential corruptions by judges, such as a judge who is more generous than his colleagues in certain types of cases. I am told by a few involved in the effort that it was the intent to “psychologically force” judges to always go in the same direction. But then might you have a judgment biased by standards of judgment that are not necessarily justified?

And I told my colleague the reality is large companies and firms can afford (and will use) this type of data analytics to their advantage to influence a judgment decision, which really should not be possible, since it makes justice even more unequal, fracturing it even more, especially between the rich and the poor. Forget about the Americans. They are lost. And no, not entirely across the French system to “improve” justice. Even the Americans will admit algorithmic bias has made their system septic.

But on a subject as important as justice (note I have removed my almost-ever-present cynic’s hat), it would be beneficial for the French legal system to do its own in-depth study to define the role of AI (even if it is an abuse of language) and deep learning in the contributions they can make.

And if you look hard at this, it is not a question of banning AIs from predicting judges’ behavior, but of banning AIs from predicting and statistics relating to a given and identified judge. But therein also lies the judges’ issue. Their fear is the data will not be pseudonymised and it will lead to justice control authorities detecting cases and judges that need to be monitored more closely.

The future of AI in French Law

Daniel Chen of the University of Toulouse Capitole in France has looked at the credibility of certain decisions rendered by court judges. His focus has been that automatic learning will learn from decisions already made in courts and tribunals, make analyses and make improvements on those containing human bias. But, once again, big data, automatic learning and artificial intelligence may try to steal the spotlight from French judges.

In the U.S. predictive forensic analysis promises to increase the fairness of the law, finding inconsistencies in judges’ behavior. By predicting judicial decisions with more or less precision, depending on judicial attributes or procedural characteristics, it evens the playing field. Automatic application may identify cases where judges are most likely to allow additional legal bias to influence their decision-making.

In particular, low predictive accuracy can identify cases of judicial indifference, when the characteristics of the case (interaction with judicial attributes) do not have a judge in favour of one outcome or another. In such cases, prejudice can have a greater influence, implying the fairness of the legal system. And the problem is more and more U.S. judges are venturing into the vast world of politics and other areas that could influence their judicial decisions, only one element that would be a cause of judicial biases. And no surprise: behavioral biases are more likely to occur in situations where judges are closer to the subjects of law.

At the end of the day, despite all the tired jokes about France, the French ban on judicial analytics is still about measurement and power – the two themes that began this post. There isn’t a profession in the world that wouldn’t impose such a ban on measurement and analysis of this sort about themselves, if they could get away with it.