The singer Bing Crosby revolutionised recording technology because he was exhausted from making so many shows. Silicon Valley was the winner.

He enabled a whole U.S. industry to rip off German tech – patent-free.

22 December 2023 — After spending 3 years on Wall Street I went to law school, then came back to The Street to land at the Law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton. How long ago? Well, George Cleary, Leo Gottlieb, Mel Steen and Fowler Hamilton were all still alive and they had their own special wing in the office. Fowler Hamilton often came into the office canteen to get his own coffee.

And I was lucky. My office was next to senior partner Alton Peters (husband of one of Irving Berlin’s daughters) and he had Irving Berlin’s Oscar for “White Christmas” on a special table in his office, with a special light over it. He had great tales about the creative process that Irving Berlin went through to write songs, and he had great stories about Hollywood and the entertainment business. Alton actually had numerous occasions to meet Bing Crosby.

It was years later that I had begun reading the work of Paul Ford (much of that work condensed in his book “The Secret Lives of Web Pages“) and I had the opportunity to meet him at a Wired magazine conference. I am sure many of you have read his articles in The New Yorker, Wired magazine, etc. He is a writer, editor, and programmer. He was one of the first bloggers – he started well before the term “blog” was even coined – and programmed all his own web publishing software himself. His book explains what happens when a web page loads into your browser – from the basic text and headlines to the moment your identity is stolen – in the most engaging, funny, smart, and accessible way possible. It provides a deep historical understanding of how the internet works.

Paul had done an enormous amount of research on the technology for modern tape production which was literally imported into the U.S. from Nazi Germany, which used tapes to share propaganda, and which was improved upon greatly by engineers at Ampex, one of Silicon Valley’s first electronics firms.

And Bing Crosby had a huge role. In the 1940s, Crosby invested $50,000 (an equivalent in purchasing power to about $1.1 million today) in Ampex, then an early developer of magnetic tape for audio recording. He did it, in part, because he used the company’s technology for his radio broadcasts and they needed a way to commercialize it.

Some background

Bing Crosby was the most successful entertainer in the world during the first half of the 20th century. He rose to the top in everything he tried his hand at – records, movies, radio, live performances. He even defined a new cultural tone, which people called “cool”. I once heard a music critic describe Crosby at his peak as the coolest white man on the planet. That’s not a bad way of conveying his appeal. Cool started out as a jazz style, but Crosby turned it into a consumer lifestyle. By the 1950s, everybody in America wanted to be cool.

But Crosby showed how it was done back in the 1920s and 1930s, mastering a panoply of attitudes that emphasized his relaxed, laid-back persona. It shaped everything, from his way of speaking to how he walked and gestured. And especially how he sang.

But few people know how much Crosby’s coolness depended on technological innovation. His impact as a technologist was just as great – maybe even greater – than his influence as an entertainer. At several key junctures in his career, Bing embraced a new technology, and revealed its potential in ways that changed the course of entire industries.

During the 1920s, microphone and amplification technologies made huge improvements, and Crosby understood better than any other vocalist what these new developments meant. Previously star singers had learned to project their voices as loudly as possible – they needed to do this to reach listeners in the back of the theater or concert hall. Bing Crosby changed all that.

Before Crosby (let’s call it B.C.), the more famous you were, the louder you had to sing – because your audience was so large. (Opera still bears the lasting mark of that rule.) But after Bing, the exact opposite was true. For the first time, a skilled vocalist could entertain a huge crowd, but still sing in an understated, conversational manner.

But few singers understood this at first. Most considered microphones as a tool for amplification, not a pathway to a different way of singing. And even those who grasped the potential were often unable to take full advantage of it – doing so required them to re-learn all the basics of their craft, from melodic phrasing to syllabic enunciation.

Crosby showed them how it was done. He learned all the tech behind microphones, how to modulate the tech, etc. In Ken Bassin’s book about the history of technology during this period he notes.

Microphones changed everything. Bing Crosby learned than rather than spraying the balcony with emotion (or using a simple megaphone for amplification) the microphone could be used to make the act of performance more intimate, the singer more vulnerable, so he practiced with different modifications and techniques. Far more vocal subtlety could be transmitted. The dynamics of entertainment allowed for quiet. A different sort of voice found its place on stage and in recordings: the crooner was born.

While others struggled with this technological step-change, Crosby completely rewrote the rule book for popular and jazz singing. We’re still dealing with the consequences today. In fact, you could draw a straight line from Bing Crosby’s “Mary” to Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy”. This created a revolution in the music business.

They called this new low-key style “crooning.” And no crooner was more popular than Bing Crosby. Just consider the number one hits he enjoyed in the 1930s (38) – which climbed to the top of the charts, followed by weeks in that position.

And other singers learned from him, even the greatest. Just compare how Louis Armstrong’s singing evolved between the late 1920s and early 1930s. In Laurence Bergreen’s brilliant biography about Armstrong, he talks about an Armstrong performance when he sings with his wife Lil Hardin Armstrong – but the vocals are so powerful, it sounds like they’re having an argument. But after watching and listening to what Bing Crosby was doing and the “crooning revolution”, Armstrong became one of the most flexible and nuanced singers on the scene and quickly adopted the new microphone “tech”. Bergreen says Armstrong was able to achieve an intimacy in his public performances that it he would not have been able to achieve – and Crosby led the revolution. He quickly understood the potential of the latest technology.

And, of course, there just had to be the “Moral Police”. From Ian Whitcomb’s anthology “The Coming of the Crooners”:

The press had a field day disseminating the attacks on the “crooning boom” by moral authorities. In January 1932 they quoted Cardinal O’Connell of Boston: “Crooning is a degenerate form of singing…. No true American would practice this base art. I cannot turn the dial without getting these whiners and bleaters defiling the air and crying vapid words to impossible tunes.” The New York Singing Teachers Association chimed in, “Crooning corrupts the minds and ideals of the younger generation.” Lee DeForest, one of radio’s inventors, regretted that his hopes for the medium as a dispenser of “golden argosies of tome” had become “a continual drivel of sickening crooning by ‘sax’ players interlaced with blatant sales talk.”

Rudy Vallee was the first famous crooner, and the foremost, but Crosby redefined the field. In the 1930s he recorded “Learn to Croon”. All hopes for the abolition of crooning were dashed by the rise of radio, a crooner’s medium. Crosby became a radio megastar. The other greats – like Bob Hope, Fred Allen, and Jack Benny – each came up in vaudeville, and their pacing reveals their early stage training; they project. Crosby did stints in the vaudeville-circuit theatres, too, but the bemused, pipe-smoking, golfing fellow who drifted in and out of song was born of the possibilities of the microphone.

Just a decade later, Crosby launched another technology revolution in entertainment. And this time he helped create Silicon Valley.

The Apex story

There are a few stories about the strange ways in which music made Silicon Valley possible. But Crosby’s role in the rise of Ampex is the most fascinating chapter in this story. Ampex revolutionized data storage – the cornerstone of the tech revolution – but only because a famous jazz singer felt overworked, and needed a way of pre-recording radio shows that sounded as good as live broadcasts.That singer was Bing Crosby.

Bing was the most popular musician in the world – and it wasn’t just “White Christmas,” which sold more records than any other song in history. He eventually recorded more than 1,600 songs, and more than forty of them reached the top of the chart. But he was just as popular in movies, winning the Oscar for Best Actor in 1944, and getting nominated again in 1945. During that same period, Crosby was tireless in touring and entertaining troops overseas.

But it was his radio show that proved to be too much.

Because of the time difference, Crosby had to do two different live broadcasts – and the network refused his proposal that they pre-record the later West Coast show on 16-inch transcription disks, basically a very large phonograph record. NBC had good reason for this. The sound quality on the disk recordings of that day were noticeably inferior. And the disks were cumbersome to edit – negating one of the major advantages of pre-recorded shows.

Crosby needed better recording technology. And in 1947, a stranger from Northern California made the trek to Hollywood with a big box that not only solved Bing’s dilemma, but set the wheels in motion for a whole host of later innovations.

What Jack Mullin did at MGM Studio that day is almost like a magic trick. He set up a live performance behind a curtain, and then followed it with a playback from his magnetic tape recorder. The audio quality was so true-to-life that many listeners couldn’t tell the difference. A private demonstration was arranged for Crosby at the ABC Studio on Sunset and Vine.

Crosby knew immediately that this was a huge breakthrough. But the price of a single Ampex 200-A machine was $4,000 – more than many people paid for a home back then. In fact, the average median family income in the US that year was just $3,000. But Crosby wanted to buy 20 of these machines. He offered to pay 60% of the money up-front.

Thus, a few days later, a letter arrived in the Ampex office with a Hollywood postmark. Inside was a check from Bing Crosby for $50,000.

ABOVE: an Ampex tape from 1960. I could not find one from the 1940s.

The whole story begins with a mystery about Nazis.

Long before he became chief engineer for Bing Crosby Enterprises, Jack Mullin was a major in the US Army Signal Corp, who spent a lot of time listening to Nazi radio broadcasts during World War II. Unlike his colleagues, Mullin was puzzled by the classical music he heard coming out of Germany – it sounded like live performances by orchestras, but somehow he doubted that the Berlin Philharmonic was really giving a concert so late at night.

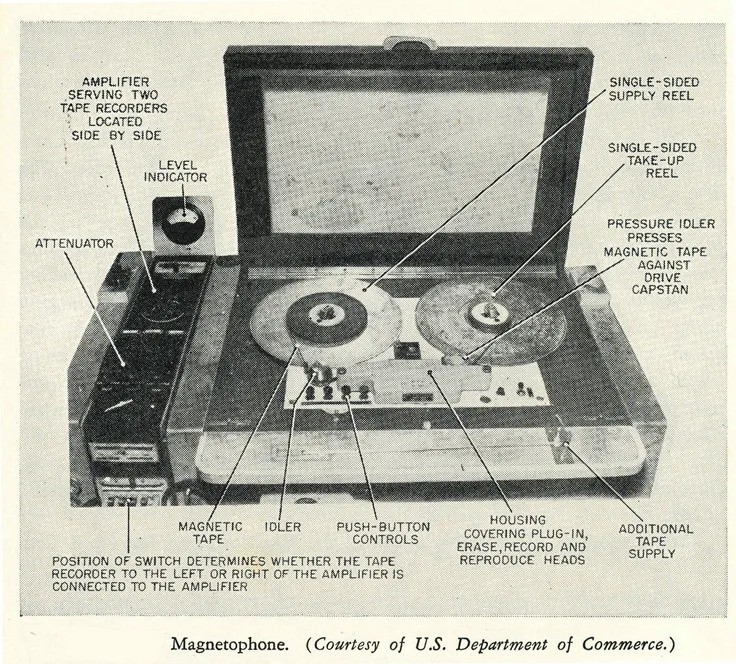

After the end of the war, he solved the mystery. The army sent him to Germany to document their electronics technology. The Second World War had just ended. Americans were picking over the technological remains of German industry. One of the things they discovered was magnetic tape; the Nazis had been using tape recording to broadcast propaganda across time zones. It was a remarkable invention. Previous sound-recording technologies had used wax cylinders or discs, or delicate wires. But magnetic tape was remarkably fungible: it could be recorded over, cut and spliced together. Plus it sounded better. This device, known as the Magnetophon was even used by Hitler to pre-record speeches, which could later be broadcast on the radio as live announcements.

ABOVE: a German Magnetophone from World War II

Mullin returned to California, after the war, with two of these tape recorders, and plenty of tape, along with instruction manuals and schematic drawings. His goal was to create his own tape recording equipment with American parts. On May 16, 1946, Mullin gave a demonstration of German Magnetophons at the NBC Studio in San Francisco. The buzz it created soon led to the launch of Ampex.

The tape recorder may not seem like a high tech device, but tape storage existed before disk storage, just as disk storage happened before cloud storage. And they all trace their origins to Thomas Edison, whose invention of the record player and motion picture were actually solutions to data storage problems. Few people today understand how advances in data storage have always been linked to music and movies. Long before personal computers appeared on the scene, the entertainment business funded these tech innovations. Even in recent time, streaming tech was bankrolled by music and movies.

Crosby is a major figure in this story, perhaps the most important of all.

Ampex, launched in San Carlos, California in 1944 is the key connecting point between music storage and data storage. That tiny startup, according to Silicon Valley historians Peter Hammar and Bob Wilson, was involved directly or indirectly in the launch of “almost every computer magnetic and optical disc recording system, including hard drives, floppy discs, high-density recorders, and RFID devices, and Bing Crosby made that all possible with that initial investment”.

ABOVE: an Ampex two-track, four-track, and sixteen-track recorders

Crosby himself moved to Silicon Valley in 1963, buying a home in Hillsborough for $175,000. (The house stayed in the family and was recently sold for $14 million). According to his son Nathaniel, Crosby and his wife Kathryn didn’t want to raise their children in Hollywood. A few months later, they moved to an even larger house on the other side of town.

By any measure, Bing Crosby’s life was an amazing success story. And he understood the financial upside enough to become a West Coast distributor for both Ampex and 3M magnetic tape. But if he had taken equity positions in Silicon Valley startups, instead of just financing them as a customer and distributor, he might have become the godfather of high tech – and the Crosby family would be on the Forbes billionaire list today. Maybe even at the top of the list.

Just consider some of the long-term results of the magnetic tape revolution in entertainment – not even including what this storage tech did for personal computing. After the introduction of magnetic tape, radio and TV shifted from live entertainment to pre-recorded shows.

That’s now the model for almost everything you watch on a screen, from Netflix to YouTube. Crosby’s advocacy of tape made it possible to edit music and broadcasts – which was almost impossible previously. You could even call him the originator of cut-and-paste. Sound quality improved dramatically with the introduction of magnetic tape. The whole high fidelity revolution grew from this starting point.

The videotape recorder was developed at Ampex (by Ray Dolby), thus facilitating the widespread dissemination and preservation of film and television programming. Even today we “push play” to start online videos – much like the first users of Ampex tech.

Many other ingredients of entertainment that we now take for granted came out of the tape revolution – encompassing everything from the ridiculous (the laugh track on TV shows) to the profound (multi-tracking in the recording studio).

I like to imagine what else Bing Crosby could have done in Silicon Valley in the 1960s and early 1970s, if he hadn’t been spending so much time on the golf course. Crosby wasn’t afraid to make risky investments. In 1948 he became a major investor in Minute Maid, which introduced concentrated frozen orange juice to the mass market. He was also one of the owners of the Pittsburgh Pirates, and made various oil and real estate investments on the West Coast.

Under slightly different circumstances, he could have established the venture capital model that now pays most of the bills in his old Hillsborough neighborhood. Bing had the vision – he had proven on two momentous occasions that he understood how tech could change the world. He also had cash to invest, and was now on the scene in Silicon Valley to put it to work.

Why didn’t he do so? Paul Ford thinks “he was just too cool”. You need to be more intense to end up like Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates. But Crosby was out playing golf and joking with his friends, when he wasn’t flying down to Hollywood to make a movie or TV appearance.

And truth be told, Bing Crosby didn’t need more money or a tech empire. But we might all be better off, if people with his cool cultural acumen had made the key decisions on tech platforms. He made singing more nuanced and aligned with people’s feelings. Wouldn’t it be great if he had done the same thing with Silicon Valley?

The legacy

Bing Crosby had an estimated net worth of $200 million at the time of his death. Yes, we associate him with the ever-popular holiday classic “White Christmas”, a key part of the U.S. emotional regression that occurs every Christmas. A good chunk of his income came from album sales, concerts, movies, and TV shows. But his wealth was due not so much to his song catalog but his brilliant investments.

And I know that Crosby is also remembered as a sometimes-brutal father, thanks to a memoir by his son Gary. But less is remarked upon is Crosby’s role as a popularizer of jazz, first with Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, and later as a collaborator with, disciple to, and champion of Louis Armstrong.

And hardly remarked upon at all is that Crosby, by accident, is a grandfather to the computer hard drive and an angel investor in one of the firms that created Silicon Valley.

And some side notes

The Ampex sign – which stood over Redwood City since the early 1940s – was a Silicon Valley landmark, but was taken down in 2018. At the time one Silicon Valley pundit noted:

“My God! Horror! What would happen if somebody bought the house at 367 Addison Ave. in Palo Alto and decided to tear down the outdated garage where Bill Hewlett and David Packard started Hewlett Packard?”

And Ampex still exists as a smaller company focused on various kinds of recording. But the company is not what it was; for some time, it was a major manufacturer of equipment in America, a key player in early Valley history: as tape recording caught on, along came computers with stored programs. Magnetic tape was an improvement, in many regards, over punched cards or paper tape; it could more readily store data and programs and play them back. From the roots put down through Ampex came a revolution in data storage.

Tapes were still awkward beasts, however – a tape is essentially a long piece of string. If a piece of data is at the end of the string, you have to spin the tape until you get to the end. As anyone who grew up on old machines that used cassettes to store programs knows, with tape the basics of computing – storage, retrieval – take what, to modern sensitivities, feels like an eternity.

In the nineteen-fifties I.B.M. developed a research project to create the RAMAC, for Random Access Method of Accounting and Control. Roughly the size of a washing machine (and that was just the disk), RAMAC was a set of platters that held about five megabytes of data—about as much data as is in a single longish MP3 today. Behold the glory of this majestic device:

NOTE TO MY READERS: This was, of course, the first hard drive. If you really want to get into this, read “Magnetic Disk Storage: A Personal Memoir” by Albert S. Hoagland, who worked on the RAMAC. He notes the Crosby connection, and in fact goes into detail on how the singer’s unusual professional needs led to tape recording and revolutionised the recording industry.

And so there is a direct link in the Silicon Valley understanding between Bing Crosby’s crooning and the rise of the hard drive, which was designed as an improvement over magnetic tape. Or, to put it into an equation: microphones + crooning + Nazis + radio + fifty thousand dollars = Silicon Valley.

So RAMAC was victorious for awhile, and although you’ll still find tape for data storage, the world belongs to the hard drive. But only for now. S.S.D.s – solid state disks, banks of memory – are taking over. The link to the Nazis and magnetic tape is slowly breaking apart.

Crosby’s career was built on technology, and he used technology to become a master of artifice: to sing as if he were sitting next to you, even if he were in California and you were in New York. He was an investor with a clear motive – a desire to stop recording live – but the ancillary benefits of tape, which could be rearranged with a razor blade, were useful to him as well.

And it was a pattern of his life: he also invested in fast-freezing technology, and hence became chairman of the board and chief promoter of Minute Maid. When the company went public, he rang the bell at the Stock Exchange. “White Christmas” and orange juice and bad parenting are the memories he left, along with countless songs – and some damn shrewd investments.

His artifice was a means to an end. And perhaps the best story of all? Once while editing his show on tape Crosby asked for a joke to get a different reaction – for a past laugh to be spliced in. Thus, in addition to setting in motion the technologies that brought about the information revolution, he also indirectly created the laugh track.