I suspect each phase of the continuing dismantling of America begins with “In a 6-to-3 vote the U.S. Supreme Court decided …”

3 July 2023 – – The annual term of the U.S. Supreme Court begins, by statute, on the first Monday in October. Court sessions continue until late June the following year. The Term is divided between “sittings,” when the Justices hear cases and deliver opinions, and intervening “recesses,” when they consider the business before the Court and write opinions. Sittings and recesses alternate at approximately two-week intervals.

But it is the month of June on which legal analysts focus – the issuing of final opinions on the major cases the Court has heard that past year. Which all used to be pretty much a “ho-hum” affairs. But now it has become a nail-biting month, with most end-of-term decisions consistently transforming key areas of public life. This year was no exception, with decisions affecting affirmative action in colleges to voting rights to LGBTQ+ equality to the future of Native American tribes.

On top of which the Court has been battling ethics scandals and plummeting public confidence.

But no matter: the 6 rightwing justices who command a supermajority on the nine-seat bench have pushed the limits of constitutional law in the pursuit of their ideological goals.

There are yottabytes being written on how to make sense of these most recent set of decisions. Are they as bad as they seem? It seems to. I have read that “America’s democracy is in more danger now than Americans yet really think”, and “This is what happens you dally with fanaticism”. Yes, so American democracy is now toying with regression of an advanced, severe, almost surreal kind. These decisions are smoking, colossal wrecking balls to centuries of progress.

So it is now bizarre that Americans celebrate their democracy, their Independence Day, on the weekend following the Supreme Court’s release of these colossal wrecking balls. I have some thoughts on the Court’s opinions but not for this post. That will come. But herein just one historical note.

Huh. The current court might as well be the Supreme Court of 1916.

By all accounts, the roots of today’s judicial activism stretch back over 100 years to the appointment of controversial Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, a champion of “sociological jurisprudence”. Brandeis was the first liberal judicial activist to be appointed to the high court. The nomination sparked the first major confirmation fight in American history.

A century ago, liberals — then styled “progressives” – were the ones complaining about judicial activism. Especially after a set of decisions in 1895 that declared the income tax unconstitutional, fatally weakened the Sherman Antitrust Act, and upheld the breaking of the Pullman strike, the Court was accused of having taken sides in the class-based political controversies of the day. The progressives’ favorite example of judicial bias was “Lochner v. New York” (1905), in which the Court held (5-4) that a New York law limiting bakers’ working hours interfered with “liberty of contract”. The progressive campaign against the judiciary came to a climax in 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt, running for president as an independent Progressive, proposed that the people be able to “recall” unpopular judicial decisions.

Wilson, the Democratic candidate in 1912, stood with another set of progressives: those who recognized that the courts could be enlisted for reform purposes, and might even “legislate”. Their goal was not to curb judicial power, but to change judicial personnel. Legal academics like Roscoe Pound and Felix Frankfurter began to turn U.S. law schools into the incubators of the future progressive judiciary.

Brandeis was the kind of lawyer they wanted to produce. He earned the highest GPA in the history of Harvard Law School, a record that lasted for over 80 years (today’s accreditors would frown on the fact that Brandeis never graduated from college). He made a reputation as the “people’s lawyer,” defending small firms against large corporations. Brandeis had a near-obsessive fear of “bigness,” as well as a lifelong admiration for the localism of the ancient Greek polis and small-town, small-business America.

In 1908, Brandeis argued before the Supreme Court in defense of Oregon’s eight-hour day law for women workers. It was an example of “sociological jurisprudence,” arguing the economic and social facts rather than the law. Brandeis conceded the anti-court progressives’ point that the courts acted politically. He chose to accept this fact and make the best of it – “to approach the court as a political body”. Today, his victory in “Muller v. Oregon” is usually seen as unacceptably “paternalist” or “patriarchal,” because he emphasized the idea that society had an interest in healthy women having healthy children. But it became a milestone in progressive jurisprudence. The Court would take a similar approach in “Brown v. Board of Education” when it struck down racial segregation, not on the basis of law or history, but on the findings of social psychology.

Brandeis became an increasingly prominent political figure after the Muller case. He told Congress that railroads should not be given a rate increase, making the fanciful claim that they could save “a million dollars a day” by adopting the principles of “scientific management.” He defended the environmentalists who challenged the Taft administration’s insufficiently green natural-resource policy, embarrassing the president by showing that he had backdated a report by his Secretary of the Interior. When Woodrow Wilson was elected in 1912, he made Brandeis his principal adviser on matters of economic regulation, especially on the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. When Wilson sought reelection in 1916, he realized that he needed to appeal to the progressive voters who had voted for the schismatic Theodore Roosevelt in 1912. So when Supreme Court Justice Joseph R. Lamar died in January 1916, Wilson nominated Brandeis to replace him.

The Brandeis nomination shocked the Senate and sparked the first serious confirmation fight in American history. The Senate held the first ever extensive hearings on a judicial appointment, because his supporters believed that he would be defeated and needed to make a case for him. That procedure stuck and extensive hearings on judicial appointments have been held ever since.

All of the previous facts I just detailed come from “Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet” by Jeffrey Rosen, a wonderful history of the Court and American politics of that time, and Rosen includes a chapter that shows the influence Brandeis had on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, and Stephen Breyer.

But more importantly, Justice Brandeis’s long legacy can be seen …ironically enough .. in Chief Justice John Roberts today. Brandeis did not just want the Court to step aside and let progressive legislators do whatever they wanted (this was more the position of the other liberal judicial icon, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.). He wanted judges to contribute to progressive reform. He made detailed defenses of progressive policy choices in almost all of his decisions.

I do not think Chief Justice Roberts’s *creative* conservative, regressive agenda would not be one Brandeis would applaud. Those who take the U.S. Constitution and the judicial task seriously certainly have a hell of a lot of work to do if they want to undo that legacy – which, quite frankly, is a fanciful task.

But on this U.S. independence celebration period, let’s take a broader look at American *democracy*, and American history. Because I think the decision by Europeans to colonize what we now know today as North America is perhaps the most disruptive action that the human race has ever undertaken, just given America and its history.

As a writer, as a journalist, you need to try and see beyond the immediate cycles of news. And that’s a real challenge. All of the current stories that seem to have led the news over the past two years – the U.S. Supreme Court decisions, political fracture in Europe and the U.S., COVID rising (again), supply chain disruption (again), economies running amok, now the war in Ukraine – boggle the mind. To take any one of them seriously is to believe that the direction they point is the direction we will go, that we stand on the cusp of a future far, far different from our past. And I do believe that. We are going to break new ground here. In this, George Orwell had it right: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle”.

I watched a lot of the January 6th Capitol “attempted coup” hearings, and I read the entire 385 page final report. Plus I have seen the bizarre political machinations in Arizona and Florida and Texas. It seems to me this is a weirder moment in America than we think. The animating question behind much commentary on the January 6th select committee hearings was “Did it change anything?” and the answer was a resounding “No”. No one believes the Republican Party will stop Trump from the 2024 primary for his actions. If anything, the Republican Party has moved more firmly in Trump’s direction. And even if they do not go with Trump, they all still go with “Trumpian” ideas. All those court cases Trump faces? They will not see the light of day until after the election.

It was actually hard to get people to pay sustained attention to the congressional inquiry into the attempt to steal the 2020 election, even though it revolved around one of the front-runners for the 2024 election. It was an almost Olympian refusal to confront the present. I used to think it’s unlikely that the American political system collapses in the next few years. But how unlikely is it, exactly, right now? Back in January 2021 so many people got so excited about Amanda Gorman’s tone poem at Joe Biden’s Presidential Inauguration, saying “we’re ok, and all is right about the world again”. Silly, silly people. No clue on America’s well-established, long term trends.

It’s why when I have done any deep reading into American history I keep coming back to the diaries of John Adams who wrote when describing the First Continental Congress convened in 1774: “Delegates were strangers, unfamiliar with each other’s ideas and experiences and diversity of opinion. There was no unity of political beliefs”.

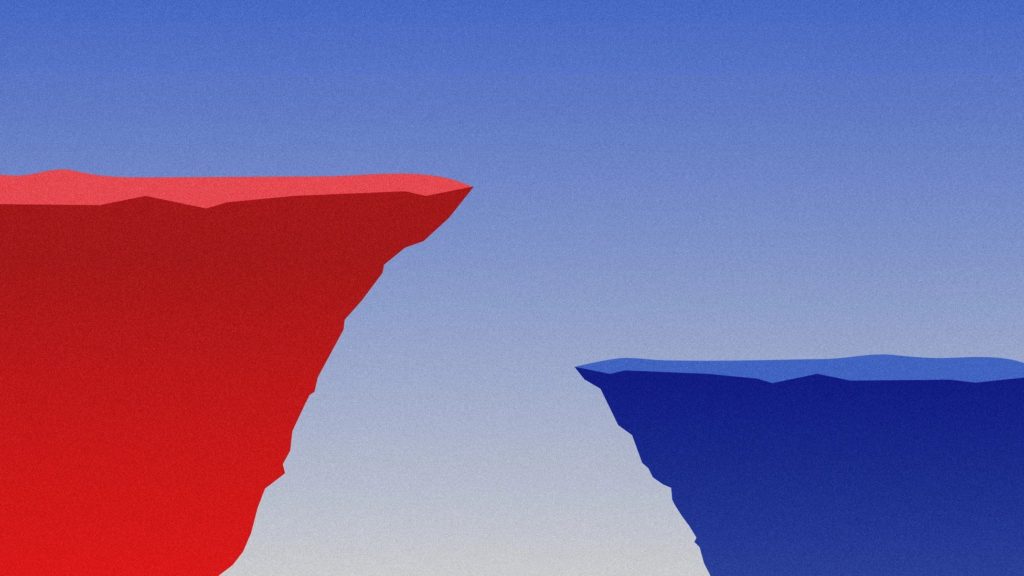

It is why I think we need to stop talking about “red” and “blue” America. What we have, really, is two blocs of fundamentally different nations uneasily sharing the same geographic space. When we think about the United States, we make the essential error of imagining it as a single nation, a marbled mix of Red and Blue people. But in truth, it has never been one nation. More like a federated republic of two nations. To borrow from an upcoming book (I have seen a draft) by Michael Podhorzer: what we have is a “Blue Nation” and “Red Nation”. This is not a metaphor; it is a geographic and historical reality.

Michael Podhorzer, a longtime political strategist for labor unions and the chair of the Analyst Institute of which I am a member, puts out a private newsletter for a very small group. He recently laid out a detailed case for thinking of these two blocs as fundamentally different nations uneasily sharing the same geographic space. I want to share a few of his thoughts and augment with some of mine.

To Podhorzer, the growing divisions between red and blue states represent a reversion to the lines of separation through much of the nation’s history. The differences among states in the Donald Trump era, he writes, are “very similar, both geographically and culturally, to the divides between the Union and the Confederacy. And those dividing lines were largely set at the nation’s founding, when slave states and free states forged an uneasy alliance to become ‘one nation’ – but never became one nation”.

Podhorzer isn’t predicting another civil war, exactly. But he’s warning that the pressure on the country’s fundamental cohesion is likely to continue ratcheting up in the 2020s. It is a multipronged, fundamentally antidemocratic movement that has built a solidifying base of institutional support through conservative media networks, evangelical churches, wealthy Republican donors, GOP elected officials, paramilitary white-nationalist groups, and a mass public following. And it is determined to impose its policy and social vision on the entire country — with or without majority support.

This is not an entirely new thought. As I have noted in many previous posts, scores of serious writers – most especially Lewis Lapham and George Packer – have laid out in detail the structural attacks on U.S. institutions which paved the way for Trump’s candidacy and will continue to progress, with or without Trump at the helm.

But I was comforted (if that is the appropriate word) to find out he and I were on the same page as to what was causing the enormous strain on the country’s ripped and mythical cohesion: “Trumpian” electoral dominance of the red states, the small-state bias in the Electoral College and the Senate, and the GOP-appointed majority on the Supreme Court to impose its economic and social model on the entire nation—with or without majority public support. As measured on fronts including the January 6th insurrection, the procession of Republican 2020 election deniers running for offices that would provide them with control over the 2024 electoral machinery, and the systematic advance of a Republican agenda by the Supreme Court, the underlying political question of the 2020s remains whether majority rule – and democracy as we’ve known it – can survive this offensive.

Politico had a long piece that defined modern red and blue America as the states in which each party has usually held unified control of the governorship and state legislature in recent years. By that yardstick, there are 25 red states, 17 blue states, and eight purple states, where state-government control has typically been divided. Measured that way, the red nation houses slightly more of the country’s eligible voting population (45 percent versus 39 percent), but the blue nation contributes more of the total U.S. gross national product: 46 percent versus 40 percent. On its own, the blue nation would be the world’s second-largest economy, trailing only China. The red nation would rank third.

Podhorzer offers a slightly different grouping of the states that reflects the more recent trend in which Virginia has voted like a blue state at the presidential level, and Arizona and Georgia have moved from red to purple. With these three states shifted into those categories, the two “nations” are almost equal in eligible voting-age population, and the blue advantage in GDP roughly doubles, with the blue section contributing 48 percent and the red just 35 percent.

All of that has led to the flurry of socially conservative laws that red states have passed since 2021, on issues such as abortion; classroom discussions of race, gender, and sexual orientation; and LGBTQ rights, is widening this split. No Democratic-controlled state has passed any of those measures. Not raised by Podhorzer but critical (I think) in understanding how far this will go is by looking at the experience of Jim Crow segregation – an important reference point for understanding how far red states might take this movement to roll back civil rights and liberties. Not that they literally would seek to restore segregation, but recent red state rhetoric (it is impossible to name all the conservative leaders that espouse this) is that that they are comfortable with “a time when states had entirely different laws” that they created a form of domestic apartheid. As the distance widens between the two sections, there are all kinds of potential for really deep disruptions, social disruptions, that aren’t just about our feelings and our opinions.

The Supreme Court decision last month effectively ending race-conscious admission programs at colleges and universities, and its decision in favor of a Christian web designer in Colorado to refuse work based on religious objections will both have a far-reaching impact on other minority groups and could open the door to a slew of cases seeking to further chip away at civil rights protections in the US. across the country. More on both of those cases in a subsequent post.

And if you read my essay from 2016, the growing separation means that after the period of fading distinctions, bedrock differences dating back to the country’s founding are resurfacing. And one crucial element of that is the return of what Podhorzer calls “one-party rule in the red nation.”

Jake Grumbach, a University of Washington political scientist who studies the differences among states and who will publish a long piece this coming fall, details how conservative Republicans have skewed the playing field to achieve a level of political dominance in the red nation far beyond its level of popular support. Undergirding that advantage, he argues, are laws that make registering or voting in many of the red states more difficult, and severe gerrymanders that have allowed Republicans to virtually lock in indefinite control of many state legislatures, and at least 10 new Congressional seats. He says “they have really stacked the deck in these states because of this democratic backsliding”.

The core question that Podhorzer’s analysis raises is how the United States will function with two sections that are moving so far apart.

I’ll close this section with this:

It’s clear the Trump-era Republicans installing the policy priorities of their preponderantly white and Christian coalition across the red states will not be satisfied with just setting the rules in the places now under their control. The MAGA movement’s long-term goal is to tilt the electoral rules in enough states to make winning Congress or the White House almost impossible for Democrats. Then, with support from the GOP-appointed majority on the Supreme Court, Republicans could impose red-state values and programs nationwide, even if most Americans oppose them. Or as Podhorzer concludes his piece: “The MAGA movement is not stopping at the borders of the states it already controls. It seeks to conquer as much territory as possible by any means possible”.

And as a European I would be remiss in not mentioning the perspective from Europe. Which is more of a foreign policy view, not a domestic politics view, but tied to U.S. domestic politics and America’s sense of itself being a *democracy*. The great paradox in the world today is that the “dumb simplicity” of America’s self-perception is both obviously bogus and fundamentally true. The story that America tells about itself and its “exceptionalism” is both the source of many of its foreign-policy disasters and the necessary myth without which much of the world would be a more brutal place.

But the dumb simplicity of America’s interventions is often infuriating and obtuse, or even disastrously naive and destructive. And yet if America stops believing in its myth, if it scurries back into the safety of its continental bunker, having decided it is now just another normal nation, then a cold wind might start to blow in places that have become complacent in their security. When the dumb simplicity is removed, the complexities of the world start growing back.

And it is a never-ending loop. The dumb simplicity of the idea means that the U.S. will continue going around the world offending people and annoying them. It will continue to make catastrophic mistakes, causing much more than offense, overreaching, and being resisted by rival powers. And it means that the U.S. will carry on pulling back when it realizes its myth has bumped up against a different reality.

It is in full form in Ukraine. Here is a country that is not in NATO, not covered by an American security guarantee, and without almost anything of central importance to the U.S., and yet is able, so far, to resist Russian colonization in large part because the U.S. has decided that it is in the West’s interest for Russia to fail. For Ukraine to carry on surviving, the West, led by the U.S., cannot step back from this calculation, or from America’s idea of itself.

Because despite the war being in Europe, involving European powers, with largely European consequences, America remains the essential partner for Ukraine. For most of Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and Britain, in particular, the reality that Ukraine would likely already be lost were it not for American military support has only proved the intrinsic value of living in an American world order. For others, including the French, such dependence is now a source not only of shame, but of long-term vulnerability. America might care enough to supply Ukraine today, but with Donald Trump limbering up for his second shot at the presidency, it doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to picture a time when this is no longer the case.

And that is were French President Emmanuel Macron – despite his foibles, his mis-steps, the “just-what-in-hell-does-he-want?” cloud he spews over all of us – has it right when he warned: whichever American president is in office when this is finally all over, Russia will remain – its preoccupations, fears, interests, and myths the same as before.

Europe is thus trapped between an immediate calamity on its doorstep and the whims of an unhappy American electorate. The question is not whether the U.S. will still be capable of defending what was once called the “free world” under a future Trump presidency, but whether it will any longer have the commitment to do so.

To many American policy makers, it is axiomatic that the U.S. is a force for good in the world, an indispensable power. America, unlike the British empire that came before it, supposedly embodies universal values, and it follows that what is good for America is good for the world. Yes, the U.S. might fall short of its values from time to time, and yes, it might occasionally have to do the dirty work of a superpower but, at heart, it is better than other superpowers — both current and former — because it is driven by what is good for everyone, not just for itself. Ukraine helps confirm this belief.

But that is pure myth. That myth, that idea is circular, powerful, and useful. It infuses the American order with a moral purpose as well as a justification, and in doing so drives the country to both greatness and calamity. It is an idea that convinces U.S. leaders that they never oppress, only liberate, and that their interventions can never be a threat to nearby powers, because America is not imperialist.

This fallacy, however, lies at the core of its most costly foreign-policy miscalculations. George W. Bush really did believe that he could liberate Afghanistan and Iraq, and that such liberation would be good for everyone, if only they could just see it. Even the intervention in Vietnam was partly driven by this idea. American power was necessary to protect the Vietnamese from communism, which in turn was necessary to protect the world from communism.

Yet, regardless of the totalitarian horror of the Taliban and Saddam Hussein, the American centurions that toppled these regimes came to be seen as oppressors, just as they were in Vietnam. Equally, the arrival of American forces was not seen as benign by the powers bordering these countries, whether Pakistan or China or Iran. No amount of money or troops could ever convince these countries that their national interest was the same as America’s. What’s more, in each of these wars, the U.S. could never care as much as the neighboring power, for whom there was never an option to cut and run. In each case, geography trumped interests.

For Ukraine, America is and will remain a force of liberation. Yet, it is not unreasonable for the rest of Europe to worry that history may repeat itself. What if Ukraine is not Greece or South Korea — where American might guarantees somebody else’s freedom — but Afghanistan where it tried, failed, and eventually gave up? Ukraine, too, has a country on its border that has decided on a policy that cannot be brought into line with America’s. Neither carrots nor sticks are likely to change Russia’s fundamental assessment of its interests.

Even the current U.S. administration is under no illusion that so long as Russia remains in conflict with Ukraine, even if Moscow is stuck and unable to achieve its goals, it will always be able to rain down missiles on Kyiv, making it almost impossible for the West to restore a settled free, democratic Ukraine, just as Iran was always able to destabilize Iraq, Pakistan likewise in Afghanistan. What then?

And that is what Ukraine fears – and others in Europe expect. In the end, what really matters is which story America believes, and for how long.

The Fourth of July in the U.S. is usually a day of community, celebration, and joy. It is the country’s national birthday party – the commemoration of a Declaration of Independence that changed “the course of human events.” It is a day of star-spangled banners and national pride – and of course the requisite hot dogs, fireworks, and parades.

But today, this year, the unity of that nation, its destiny, its self-confidence, the self-evidence of its truths are being pulled apart by forces of such strength that many wonder whether that nation, “so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” Is there reason to celebrate this Fourth, or is a more fitting response to mourn what once was and what is currently in jeopardy?

This last U.S. Supreme Court term will be remembered as the moment a cynical and anti-democratic movement, decades in the making, reached its zenith, empowered by bad faith and opportunism. Now the cabal lords its power over a broken political system from a perch of increased influence and lack of accountability. This is power politics by unelected actors, appointed largely by men who lost the popular vote for president. Its path was paved by Mitch McConnell’s Machiavellian exploitation of the deaths of two justices. He was a master of shamelessness with a single purpose – to accomplish via judicial appointment what he could never have achieved through democratic means.

The damage he and his hard-right radicals have wrought touches all aspects of society, from abortion rights to commonsense gun control to the environment to the evisceration of the separation of church and state. What we have are the ruins of what many took for granted as our constitutional rights. And nothing suggests these justices are anywhere near sated.

And the obvious. The justices tried very hard, for a very long time, to cultivate a perception that they existed on an elevated, erudite plane far above the petty concerns that occupy elected politicians. They said the court’s work was wholly separate from considerations like public opinion. Even when they had to take up a case with political implications, they approached it only as a question of legal scholarship, not sullied by ideology or policy preferences.

That image is all but dead.

When history looks back on the term that just ended, what stands out the most may not be any one ruling, but rather its place in the trend — long-simmering, but quickly accelerating — toward seeing the court for what it is: the single most powerful weapon in U.S. politics. At every turn, the court looks more like run-of-the-mill, outcomes-driven, raw-power politics.

And the stench. Wealthy GOP donors with interests before the court paid for luxury vacations for Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, who didn’t disclose those gifts. The justices’ reaction hasn’t helped. Alito, borrowing a page from any decent political operative’s playbook, tried to get ahead of the story, pre-butting ProPublica’s investigation with a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

And confirmation hearings? A circus. Start the clock on that trend wherever you want — Robert Bork, Thomas, Merrick Garland. But we’ve ended up in a place where the Senate treats the process like the prize fight it is — not neutral intellectual pursuit, as it was once framed. As recently as the Obama administration, Supreme Court nominees got broad bipartisan support. That’s not coming back.

You can even see it in the court’s writing. Last week’s affirmative action rulings were highly charged and highly personal — a far cry from dispassionate legal interpretation. The dissents were bristling.

And reality check: the court hasn’t become political. An institution with this much power to decide inherently political issues — from voting rights to campaign finance law to matters of life and death, what the federal government can and can’t do, limits of the First Amendment, even who gets to be president — is, and has always been, a political institution. Perception is finally catching up to that reality.

But relax. Tomorrow, celebrate with the Americans … and go out and eat a hotdog.