The “it can’t happen to us” moment is happening to us right now. We just don’t feel it yet.

As Ben Franklin said “We gave you a republic … if you can keep it”. And unless a miracle happens this Tuesday, we didn’t. Democracy is on the ballot and unfortunately I think it’s going to lose. And once it’s gone, it’s gone. It’s not something you can change your mind about and reverse.

But whatever happens, it will be momentous.

6 November 2022 (Washington, DC) – And so the sun rose on this Sunday before Election Day. Our clocks, like much of the spirit of the country, feel off. We have gone back an hour, and we worry we are about to be set back in a profound and inescapable way as a nation of rights, laws, democracy, and hope. Mixed in with feelings of disorientation are swells of anxiety and even fear. Many of us scour the news looking for clues as to what might happen – the polls, the early vote totals, what we are hearing anecdotally from family and friends. We grasp at data points seeking to settle the pit in the stomach or to confirm our dread.

But it is important to face facts. Too many Americans refuse to do just that – which is a big part of what got them into this mess. And the facts are what they are. There is a sizable movement in this country that seeks to literally vote out democracy. This movement is fueled by a coordinated campaign on right-wing media. It exploits the frailties of American institutions. It weaponizes lies. And it leverages its fractured technologies to turn the very notion of “the truth” into a partisan attack line. Too many of my American friends are clinging with ten fingernails to the idea that their institutions are robust enough to withstand fascism. They are not.

When I was planning this trip to the U.S., I knew I would be here for the midterm elections on 8 November. I was dreading it. On the plane ride over I had sketched out a pre-election post to distribute today. I felt America had reached its “crossing the Rubicon moment” – the slide into authoritarianism was simply unstoppable. A friend sent me Bill Maher’s weekend commentary (Maher ends each of his 1 hour shows with a commentary) and he used the “crossing the Rubicon moment” to a better degree than I did to explain this week’s vote, so I’ve included it below – both the original video and a few of the best lines from the transcript. His thoughts are my thoughts.

But before you watch/read Maher’s commentary, herein a few of my thoughts to put the short Maher piece in a broader perspective. This is a long post so please bear with. It is a collection of thoughts rather than a clear narrative, part of my book-in-progress entitled “Tales Aboard the Shipwreck Called Civilisation”.

We have forgotten our history – assuming anybody has actually read it. The arc of the moral universe does not bend toward moral progress and justice. Freedom, democracy, liberalism are mere blips on the screen of humanity. Autocracy, totalitarianism and dictatorships have long ruled the roost. And for those tech nerds among us, we made that constant mistake of correlating advancements in technology with moral progress. We metastasized into an army of enraged bots and threats. That blip of tech nostalgia and cheer has long been forgotten.

So it is not hard to see that the world has come to a critical juncture, a point of possibly catastrophic collapse. Multiple simultaneous crises – many of epic proportions – raise doubts that liberal democracies can govern their way through them. In fact, it is vanishingly rare to hear anyone say otherwise.

While thirty years ago, scholars, pundits, and political leaders were confidently proclaiming the end of history, few now deny that it has returned – as if it ever ended. And it has done so at a time of not just geopolitical and economic dislocations but also historic technological dislocations. To say that this poses a challenge to liberal democratic governance is an understatement. As history shows, the threat of chaos, uncertainty, weakness, and indeed ungovernability always favors the authoritarian, the man on horseback who promises stability, order, clarity – and through them, strength and greatness.

How, then, did we come to this disruptive return? Explanations abound, as I briefly chronicled in my “Postscript” to a post I published earlier this weekend. To expand on that “Postscript”, we need to look at:

– the collapse of industrial economies and the post–Cold War order to the racist, nativist, and ultranationalist backlash these have produced

– the accompanying widespread revolt against institutions, elites, and other sources of authority to the social media business models and algorithms that exploit and exacerbate anger and division

– the sophisticated methods of information warfare intended specifically to undercut confidence in truth or facts to the rise of authoritarian personalities in virtually every major country, all skilled in exploiting these developments

All these points are interconnected and collectively help to explain our current state. But as Occam’s razor tells us, the simplest explanation is often the best. And there is a far simpler explanation for why we find ourselves in this precarious state: the widespread breakdowns and failures of governance and authority we are experiencing are driven by, and largely explicable by, underlying changes in technology.

We are in fact living through technological change on the scale of the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, but it is occurring in only a fraction of the time. What we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority, primarily but not exclusively governmental – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one. All of these other features are just the localized spikes on the longer sine wave of history.

Ten years ago I was invited to a presentation and book signing by George Packer who had just published “The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America”. Those of you who read his 2006 book “Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq” know the depth and quality of his work. “Assassins’ Gate” is considered the definitive work about America in Iraq, but as I noted in my review of the book it also describes the prominent place of the war in American life.

In his presentation on “The Unwinding”, Packer provided details supporting his broad hypothesis that the rise of the Internet would lead to the breakup of governments and nation-states, and the emergence of new competitors, thanks to the democratization of consumer choice and the demise of territorial boundaries as a constraint, just as had already begun happening in most private-sector businesses and industries. In his book he explains how technology enabled individuated politics and party fracturing, and how most of the other features of American politics in the last decade had flowed logically from the consequences of the Internet’s emergence. But for various reasons only the conservatives and the far right realised its true potential. And the money shot:

“Until now, conventional wisdom has held authoritarianism to be winning its global struggle with democracy. Instead, it should have been clear before now that we are actually living in a world increasingly dominated by digital technologies, even in war, where territory is largely irrelevant and everyone in fact wants to determine his or her own destiny. Democracy is indeed under attack from authoritarian forces. It always will be. But our domestic combatants will take advantage, too. Because in America the danger will always be from within. It can only survive if those who want it fight back – though in a very different form from what we have come to expect. Like virtually everything else”.

This, then, is a discussion of what the new technological realities mean for the future of power and its control through governance, especially in America. But I do not have the space (or you probably do not have the patience) for a full blown discussion of technological determinism. But suffice it to say technologies themselves are not inherently authoritarian – or otherwise ideological – and current digital technologies certainly are not. These technologies are what we make of them. But to some degree, we also are what these technologies make of us – or, more precisely, once we make them, they then make the world that shapes our thoughts, actions, and lives. While the dominant technology of any era shapes not just what people do but also how they conceive of the world around them, it can be used quite cleverly to dictate the paths that people ultimately choose.

Hence the unique gifts of the Trump Mob, and the sway of right-wing media, and the cynical calculations of conservative politicians, have been able to use the changing demographics of the United States and the mis-development of the world more broadly, to take all the economic vicissitudes of the last decade and reshape them to their advantage – the liberal contingent always kept on its back foot.

Look, history is contingent, and the sand pile we live on could shift or collapse at any moment as each new event, like another grain, is added to it. Yet these shifting sands rest upon deeper tectonic plates that shape the overall unfolding of American history for at least the last 40 years – something I will address further on in this essay.

Just as in previous technological transitions, all social constructs currently taken largely for granted are changing: the structure of the family and gender relations, the place in our lives of religious belief, the nature of the economy, the distribution and geography of political power, the definitions and interrelations of social classes, the bases of self-identity, and the sources and existence of truth and reality themselves. The Protestant Reformation, whose “true and enduring radicalism,” in the words of historian Alec Ryrie, lay in “its readiness to question every human authority and tradition” was made possible in large measure by the information technology revolution of its day – the invention of the printing press – and unleashed conflicts and violence that eventually led to the emergence of the modern nation-state as the means for containing it. We are experiencing a similar upheaval today, with widespread challenges to authority and tradition posing direct threats to nations and governing systems. Nor should it surprise us that all this has induced violent backlash and extreme polarization.

This technological explanation at first may seem impersonal, deterministic, and therefore depressing. But it is none of those things: We are living through a historical earthquake. Countries, government, democracy – at least, as we now know them – are all collapsing. That, we cannot change.

Truth has simply disappeared. “Truth is gold” is something I constantly hear. Well, if so, that means you can melt it, bend it, flake it, fake it, or pound it into dust. Reality, in today’s world, is something you knead. Social media and our mobile phones have made us stupid – allowing us to skate over the surface of life, touching things lightly but never getting caught in the real essence of what is going on, and why. And the ogres amongst us know this, and they have mastered language and culture. I often hear that literary and political culture, or even just plain truth-telling, is in itself a bulwark against all of this. But the facts don’t bear out the hypothesis. Literary culture is certainly no remedy for totalitarianism. Ogres gonna ogre. Rhetoric is as liquid and useful for the worst as it is for the best. The humanities, unfortunately, belong to humanity. And you can’t put that genie back in the bottle.

I am not going to bore you with a litany of past authors and references that predicted where we’d be today, almost preordained plans of our development.

But I will quote two prolific people whose work I have read in their entirety: Hannah Arendt and Jacques Ellul. Arendt was a German political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor who became an American citizen in 1950. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century. Ellul was a French philosopher and sociologist who had a lifelong concern with what he called “technique” which predicted the dominant role of technology in our contemporary world.

Hannah Arendt, in The Origins of Totalitarianism (published in 1951), describes the susceptibility to propaganda of the modern masses who would become “atomized”, subject to modern social processes that would create groups and defined identities, destroying a common whole and so would be “obsessed by a desire to escape from reality because in their essential homelessness they can no longer bear its accidental, incomprehensible aspects, and stress of survival”. They seek refuge in “a man-made patterns of relative consistency, of comfort, that would bear little relation to reality”. I thought about this when I watched Trump, the all-American demagogue, and his far right enablers, who easily caused their followers to abandon common sense, to abandon reality, and let Trump be their their guide to the world around them. His defeat won’t change that. It’s now too embedded in their psyche.

Jacques Ellul published three volumes which explained his thoughts in detail, explaining “technique” and the dominant role technology would play in the contemporary world. In the introduction to the first volume (1954) which I think is the best volume. He notes two overarching concepts:

“Technique constitutes a fabric of its own, replacing nature. Technique is the complex and complete milieu in which human beings must live, and in relation to which they must define themselves. It is a universal mediator, producing a generalised mediation, totalizing and aspiring to totality. Technique will be the Milieu in which modern humanity is placed.

Technology will increase the power and concentration of vast structures, both physical (the factory, the city) and organizational (the State, corporations, finance) that will eventually constrain us to live in a world that no longer may be fit for mankind. We will be unable to control these structures, we will be deprived of real freedom – yet given a contrived element of freedom – but the result will be that technology will depersonalize the nature of our modern daily life, and we shall not realize it. And it shall take forms that we cannot even today predict but that will change our Social Milieu. We will morph. We will adapt”.

But today’s technology … all of these many, many, many applications, however varied … share a certain core characteristic, most fundamentally, in that they are disaggregative. The essence of digitization is the breaking down of everything into its information component. Information is massless and occupies no space. It reduces complex systems, constructs, and interrelationships to their simplest units – which we can think of as ones and zeroes, ons and offs, signal or silence, existence or nonexistence – which can be broken apart, transmitted, and recombined to create meaning. Or no meaning. Or manipulated meaning. This characteristic compresses time, reduces cost – and renders place meaningless.

But it also points out a theme I have addressed in previous posts: the tension between the two understandings of our age’s underlying technologies: these technologies are built on network economics, which tend to scale, and thus lead to monopolization and concentration (hence the death of data privacy). But at the same time, networks are inherently disaggregating, decentralizing, and manipulative.

It certainly fits America – constantly morphing and adapting. But in the short history of mankind, the short history of nationhood, it is a very strange place. Fundamentally it has always has been a nation of madness. Mostly good madness – but madness still. The people who would build that nation must have been mad to seek “where there be dragons” – to cross storm-riven seas, arrive on the shores of this wild and magical land, and embrace the idea of living in the haunted wilderness to have the chance – just a chance – of shaping something new. Something removed from the mental and physical confinements of history. A good friend, Jack McKew, says in his forthcoming book:

In that time of wilderness, each one of us here was a zealot of some cause — a zealot of gods, commerce, ideas, quests, adventures. We came here running from things, or toward others. And this strange amalgamated zealotry was somehow integral to our survival, the good and bad forces that shaped us in their conflict. A core belief that old rules didn’t apply. That the frontier could be pushed ever outward. That we could survive against the odds. And that always, always, the sins of the past could be overcome by achieving a righteous future.

Agreed. We embraced the idea of fate when it drove us, pulled us toward success – but we were just as quick to cast fate aside when she was a cruel mistress who defined us against our will. The smallness of these last 6 years has been the hardest to define but most of my American friends told me it was “a crushing prison”, or words to that effect. The smallness of perspective, of vision, of horizon. Americans seem particularly blind to smallness, immune to the feeling of contraction as it drew in upon itself.

Many countries in the world are reviving and revamping technology-enabled systems of control and authoritarianism, or are dabbling with varieties of populism and charismatic leadership with autocratic tendencies. As I noted in a long post earlier this year, that is society’s “default”. Democracy is hard, not flashy, and it’s getting harder to show its dividends because the world grows more unequal, and because compromise is hard. In America, it’s hard and it’s so much easier to just take things over and not listen or negotiate or understand how the revolutionary rights and ideas in the founding documents of the nation can be best achieved. So much easier to succumb to the seductive calls of ill-gotten power than to constantly strive toward ideals that sometimes seem impossible to achieve.

Yes, we thought America had stepped back from the edge in 2020. But the edge was not a fixed point, and it constantly eroded, crumbling away beneath its feet. The plutocracy is entrenched, the autocracy becoming more so. And that’s the one central theme: the stickiness of plutocracy and authoritarianism. The individual leader may be ditched but not the system of power. The perpetuation of the status quo is assured.

Because those who in America who want to entrench autocracy know how technology will help. They know that today’s technologies not only destroy any notion of “authoritativeness” but also have a profoundly destabilizing effect on all forms of “authority.” As Eric Schnurer, a writer for Foreign Affairs magazine, put it so well:

“Of course, new technologies generally undermine incumbents and the existing distributions of power. But the distinctive feature of the Internet era has been the rapid disintegration of all forms of authoritativeness—especially the authority of objective reality. Alternative realities are the reality of the digital era: Second Life, forerunner of the metaverse, provided people with an alternative universe, alternative identity, and alternative economy. Augmented and virtual reality are the next logical and technological step that will make it harder and harder in the years ahead to distinguish fact from fantasy, truth from fiction, real from fake, “alternative facts”- in Kellyanne Conway’s memorable phrase – from factual facts”.

Despots, would-be or actual, depend on the destruction of truth and objective reality to undermine or discredit all other sources of authority, so that they may rule by force. In contrast, the current technological regime, in undermining all authority, including all incumbent structures of power, is as much a state-destroying force as a state-fortifying one.

Even Donald Trump, despite generally being viewed as authoritarian, encouraged vigilantism both before and even during his presidency in ways that actually promoted the undermining and dispersal of the state’s monopoly on “legitimate force.” It would be naive to see the privatization and democratization of force as something uniquely promoted by Trump, however. Indeed, this process has only gathered strength and speed since he left office. A major goal of what passes for “conservatism” today is the weakening of the state in virtually all of its forms and the return of its powers to private, and individual, hands: a sort of violent libertarianism.

And so the far right gutted The Republic and built their vetocracy – in which we all expect to get everything we want, including blocking anyone else who wants something different. Anti the “common good”. As “reality” has become more and more personalized, the right and necessity to protect that reality against alternative realities has become more compelling. Trump’s encouragement of his supporters to armed insurrection was merely a reflection of the coming “democratization” of force. It is a forewarning of the future of government of “legitimate force”.

NOTE TO MY READERS: if you have the time read “The Future of Violence” by Benjamin Wittes and Gabriella Blum. Soon we’ll all have our own drones, WMDs, or worse. The current threat in Americas, they argue, is not really a centralized “authoritarianism.” It is a dispersed reality and a nearly universal intolerance of everyone else’s. All of this is incubating within a social framework shaped largely by communications channels constructed specifically to encourage anger, disagreement, and the spread of rumor and falsehood, because these propagate most readily and thus generate the most revenue for their owners.

Unfortunately, the companies that channel our use of these technologies in this way are just a part of the economic changes rending the fabric of day-to-day reality for millions. As the digital economy displaces the analog, the value of the weightless surpasses that of the tangible, and the virtual supersedes the terrestrial, the old economy is fading, its industries, jobs, and communities with it. People rooted in the older economy are enduring the destruction of everything they have known and cared about. As a result, they are angry. And so easily manipulated – politically and socially. The old hard-won, broadly distributed middle-class economy is collapsing, its breakdown exacerbating the festering resentment already described in countless books and essays leading up to this election.

And not only has the foundation collapsed underneath most people, so has what was left of the social safetly net. As with all such economic transitions, the existing methods of “social insurance” – which over time emerge to mitigate the risks and unfairness of each “new economy” – are being destroyed along with the other social arrangements that spawned and underpinned them. In prior transformations, these were the extended family, the village, and civil society; today, it is the welfare state that originally evolved to counter the worst depredations of the Industrial Revolution. Of course, the constriction of the welfare state only further undercuts its popular support, weakening existing governments worldwide.

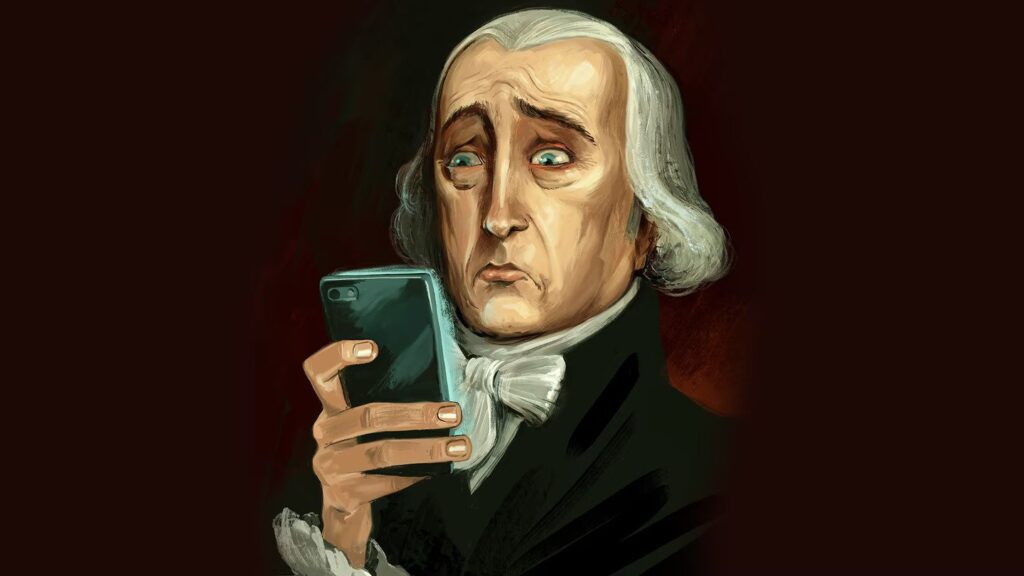

And so America is living James Madison’s nightmare. Yes, the Founders designed a government that would resist mob rule. They didn’t anticipate how strong the mob could become.

NOTE TO MY READERS: A few summers ago, and during the COVID lockdowns, in anticipation of writing this book, I re-read Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” along with all of the Federalist Papers as well as a history of the U.S. constitutional convention. All assigned readings back in my university days as a wasted youth, given new meaning in my dotage. The quotes below are from various Federalist papers.

James Madison traveled to Philadelphia in 1787 with Athens on his mind. He had spent the year before the Constitutional Convention reading two trunkfuls of books on the history of failed democracies, sent to him from Paris by Thomas Jefferson. Madison was determined, in drafting the Constitution, to avoid the fate of those “ancient and modern confederacies,” which he believed had succumbed to rule by demagogues and mobs.

Madison’s reading convinced him that direct democracies – such as the assembly in Athens, where 6,000 citizens were required for a quorum – unleashed populist passions that overcame the cool, deliberative reason prized above all by Enlightenment thinkers:

“In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.”

To prevent factions from distorting public policy and threatening liberty, Madison resolved to exclude the people from a direct role in government:

“A pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction”.

So the Framers designed the American constitutional system not as a direct democracy but as a representative republic, where enlightened delegates of the people would serve the public good. They also built into the Constitution a series of cooling mechanisms intended to inhibit the formulation of passionate factions, to ensure that reasonable majorities would prevail:

“The government cannot endure permanently if administered on a spoils basis. If this form of corruption is permitted and encouraged, other forms of corruption will inevitably follow in its train. When a department at Washington, or at a state capitol, or in the city hall in some big town is thronged with place-hunters and office-mongers who seek and dispense patronage from considerations of personal and party greed, the tone of public life is necessarily so lowered that the bribe-taker and the bribe-giver, the blackmailer and the corruptionist, find their places ready prepared for them.”

The people would directly elect the members of the House of Representatives, but the popular passions of the House would cool in the “Senatorial saucer,” as George Washington purportedly called it: the Senate would comprise natural aristocrats chosen by state legislators rather than elected by the people. And rather than directly electing the chief executive, the people would vote for wise electors – that is, propertied white men – who would ultimately choose a president of the highest character and most discerning judgment. The separation of powers, meanwhile, would prevent any one branch of government from acquiring too much authority. The further division of power between the federal and state governments would ensure that none of the three branches of government could claim that it alone represented the people.

Madison predicted that America’s vast geography and large population would prevent passionate mobs from mobilizing. Their dangerous energy would burn out before it could inflame others.

Of course, at the time of the country’s founding, new media technologies, including what Madison called “a circulation of newspapers through the entire body of the people,” were already closing the communication gaps among the dispersed citizens of America. The popular press of the 18th and early 19th centuries was highly partisan – the National Gazette, where Madison himself published his thoughts on the media, was, since its founding in 1791, an organ of the Democratic-Republican Party and often viciously attacked the Federalists.

But newspapers of the time were also platforms for elites to make thoughtful arguments at length, and Madison believed that the enlightened journalists he called the “literati” would ultimately promote the “commerce of ideas.” He had faith that citizens would take the time to read complicated arguments (including all of the essays that became The Federalist Papers), allowing levelheaded reason to spread slowly across the new republic.

What would Madison make of American democracy today? Madison’s worst fears of mob rule have been realized – and the cooling mechanisms he designed to slow down the formation of impetuous majorities have broken. The polarization of Congress, reflecting an electorate that has not been this divided since about the time of the Civil War, has led to ideological warfare between parties that directly channels the passions of their most extreme constituents and donors – precisely the type of factionalism the Founders abhorred.

The executive branch, meanwhile, has been transformed by the spectacle of a Tweeting president, though the presidency had broken from its constitutional restraints long before the advent of social media. During the election of 1912, the progressive populists Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson insisted that the president derived his authority directly from the people. Since then, the office has moved in precisely the direction the Founders had hoped to avoid: Presidents now make emotional appeals, communicate directly with voters, and pander to the mob.

Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms have accelerated public discourse to warp speed, creating virtual versions of the mob. Inflammatory posts based on passion travel farther and faster than arguments based on reason. Rather than encouraging deliberation, mass media undermine it by creating bubbles and echo chambers in which citizens see only those opinions they already embrace.

We are living, in short, in a Madisonian nightmare. From the very beginning, the devices that the Founders hoped would prevent the rapid mobilization of passionate majorities didn’t work in all the ways they expected. After the election of 1800, the Electoral College, envisioned as a group of independent sages, became little more than a rubber stamp for the presidential nominees of the newly emergent political parties.

The Founders’ greatest failure of imagination was in not anticipating the rise of mass political parties. The first parties played an unexpected cooling function, uniting diverse economic and regional interests through shared constitutional visions. After the presidential election of 1824, Martin Van Buren reconceived the Democratic Party as a coalition that would defend strict construction of the Constitution and states’ rights in the name of the people, in contrast to the Federalist Party, which had controlled the federal courts, represented the monied classes, and sought to consolidate national power. As the historian Sean Wilentz has noted, the great movements for constitutional and social change in the 19th century – from the abolition of slavery to the Progressive movement – were the product of strong and diverse political parties.

Whatever benefits the parties offered in the 19th and early 20th centuries, however, have long since disappeared. The moderating effects of parties were undermined by a series of populist reforms, including the direct election of senators, the popular-ballot initiative, and direct primaries in presidential elections, which became widespread in the 1970s.

More recently, geographical and political self-sorting has produced voters and representatives who are willing to support the party line at all costs. After the Republicans took both chambers of Congress in 1994, the House of Representatives, under Speaker Newt Gingrich, adjusted its rules to enforce party discipline, taking power away from committee chairs and making it easier for leadership to push bills into law with little debate or support from across the aisle. The defining congressional achievements of Barack Obama’s presidency, the Affordable Care Act of 2010, was passed with no votes from Republican members.

NOTE TO MY READERS: Gingrich deserves a whole post and how he helped decimate American democracy. As he saw it, Republicans would never be able to take back the House as long as they kept compromising with the Democrats out of some high-minded civic desire to keep congressional business humming along. His strategy was to blow up the bipartisan coalitions that were essential to legislating, and then seize on the resulting dysfunction to wage a populist crusade against the institution of Congress itself. His idea was to build toward a national election where people were so disgusted by Washington and the way it was operating that they would throw the ins out and bring the outs in.

Gingrich recruited a cadre of young bomb throwers – a group of 12 congressmen he christened the Conservative Opportunity Society – and together they stalked the halls of Capitol Hill, searching for trouble and TV cameras. Their emergence was not, at first, greeted with enthusiasm by the more moderate Republican leadership. They were too noisy, too brash, too hostile to the old guard’s cherished sense of decorum.

And Gingrich and his cohort showed no interest in legislating. “Forget your committee work”. He cancelled all of the education sessions that his members needed to know what their committee was about, the issues the committee addressed, etc. He told them “take care of your district, use all of your free time to go home and be visible, attend events. We’ll manage the legislative process from here. Your job is purely political”.

Exacerbating all this political antagonism is the development that might distress Madison the most: media polarization, which has allowed geographically dispersed citizens to isolate themselves into virtual factions, communicating only with like-minded individuals and reinforcing shared beliefs. Far from being a conduit for considered opinions by an educated elite, social-media platforms spread misinformation and inflame partisan differences. Indeed, people on Facebook and Twitter are more likely to share inflammatory posts that appeal to emotion than intricate arguments based on reason. The passions, hyper-partisanship, and split-second decision making that Madison feared from large, concentrated groups meeting face-to-face have proved to be even more dangerous from exponentially larger, dispersed groups that meet online.

One last side note for this section.

In 1947, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, and Oskar Morgenstern drove from Princeton to Trenton in Morgenstern’s car. The three men, who’d fled Nazi Europe and become close friends at the Institute for Advanced Study, were on their way to a courthouse where Gödel, an Austrian exile, was scheduled to take the U.S.-citizenship exam, something his two friends had done already. Morgenstern had founded game theory, Einstein had founded the theory of relativity, and Gödel, the greatest logician since Aristotle, had revolutionized mathematics and philosophy with his incompleteness theorems. Morgenstern drove. Gödel sat in the back. Einstein, up front with Morgenstern, turned around and said, teasing, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Gödel looked stricken.

To prepare for his citizenship test, knowing that he’d be asked questions about the U.S. Constitution, Gödel had dedicated himself to the study of American history and constitutional law. Time and again, he’d phoned Morgenstern with rising panic about the exam. Morgenstern reassured him that “at most they might ask what sort of government we have.” But Gödel only grew more upset.

Eventually, as Morgenstern later recalled, “he rather excitedly told me that in looking at the Constitution, to his distress, he had found some inner contradictions and that he could show how in a perfectly legal manner it would be possible for somebody to become a dictator and set up a Fascist regime, never intended by those who drew up the Constitution.” He’d found a logical flaw.

Morgenstern told Einstein about Gödel’s theory; both of them told Gödel not to bring it up during the exam. When they got to the courtroom, the three men sat before a judge, who asked Gödel about the Austrian government.

“It was a republic, but the constitution was such that it finally was changed into a dictatorship,” Gödel said.

“That is very bad,” the judge replied. “This could not happen in this country.”

Morgenstern and Einstein must have exchanged anxious glances. Gödel could not be stopped.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “I can prove it.”

“Oh, God, let’s not go into this,” the judge said, and ended the examination.

Neither Gödel nor his friends ever explained what the theory, which came to be called Gödel’s Loophole, was. It was year’s later that notes in Gödel’s files and diaries showed he had conjectured how a well-organised faction could take control of the government.

For pundits and political consultants, every election carries portents of a realignment between the two major political parties. Even midterm elections, which almost always have the same result — gains for the “out” party — are earth-shaking events, interpreted as a verdict on the president’s leadership. This week’s midterm elections are the same. But there is a long game involved, and I shall try to be brief.

The midterms of 1994 were seen as an especially crippling setback for the Democratic Party, as Republicans took control of Congress and installed gaseous Newt Gingrich as Speaker of the House — the first Republican Speaker in forty years. Yet just two years later, Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne Jr. came out with a book forecasting a new progressive era, with the title They Only Look Dead. In an afterword for the book’s 1997 edition, Dionne wrote that the 1996 reelection of Bill Clinton “confirmed what 1992 hinted at: that the conservative era that began with Richard Nixon’s election in 1968 is over.”

But others (especially Lewis Lapham and George Packer) had seen hints in 1992 that something else was afoot. That was the year Nixon’s former speechwriter Patrick Buchanan challenged incumbent president George H.W. Bush in the Republican primaries, speaking in New Hampshire of leading a pitchfork rebellion. At the GOP convention in Houston that summer, he gave a strident “culture war” address that Texas columnist Molly Ivins memorably quipped “probably sounded better in the original German.” Yet Buchanan was always more of a pundit than a political leader, and by 1997 he was alarmed by Gingrich’s “collaboration” with Clinton. Buchanan despaired for his party. “The Republican Party is today in a crisis of the soul, unable to decide who and what it is,” he wrote in his syndicated column.

We know now that the extremism and rhetorical incontinence modeled by Buchanan and Gingrich in the 1990s represented the true id —and the long-term future — of the Republican Party. Both men were harbingers of the hardline partisanship of the Bush-Cheney administration in the early 2000s, which by 2016 metastasized into Trumpism, and which now seems to have a fifty-fifty chance of leading the United States into an accelerating slide toward autocracy — or at least the kind of extended, sadistic smite-the-abortionists-and-homosexuals crusade that Buchanan was calling for.

There were many who saw it coming: they looked beyond the partisan pendulum swings. There was no permanent majority in Congress and no lasting partisan realignment. But something fundamental was shifting. A concerted assault on those who favored an expanded, inclusive democracy took hold during the Reagan years. The political system had become friendly to business interests, wealthy cranks, professional liars, and a working alliance between closet racists and open ones. The journalist William Greider described it in his 1992 book Who Will Tell the People?: The Betrayal of American Democracy, which opens with the arresting line: “The decayed condition of American democracy is difficult to grasp, not because the facts are secret, but because the facts are visible everywhere.”

The two parties, in Greider’s view, were collaborating in a slow, grinding debilitation of citizen power and participation. The Republicans were concocting a “rancid populism that is perfectly attuned to the age of political alienation—a message of antipower.” The Democrats were a hollowed-out party, operating “mainly as a mail drop for political money.” Greider reported that when the Democratic National Committee wanted to organize a celebration in 1992, DNC staffers realized the party had no working list of its membership — rich donors, yes, but not party “regulars” serving at the county and precinct levels. While the National Rifle Association claimed to have about 2.5 million dues-paying members at the time, and the AFL-CIO had about 14 million, the Democratic Party was no longer that kind of “active membership” organization. Since then, online fundraising has broadened the donor base for Democratic (and Republican) candidates considerably; still, the participation of most people aligned with the Democratic Party goes no further than casting an occasional vote, often without enthusiasm.

How is it possible that the Republican Party, with each turn of the screw, has made itself more malicious, conspiratorial, gun-crazy, and cultish, and yet still manages to run neck-and-neck with the Democratic Party? The very idea that a corrupt nabob was able to take full control of the supposedly Grand Old Party, and that he got elected president in 2016 — you want to shake your fist at the Democrats and yell, “Can’t anybody here play this game?”

There is no doubt in my mind that GOP will attempt a brazen antidemocratic scheme in the next presidential election in which they use their legislative power in a key state or two to overrule the majority choice of the voters. There are 300 election deniers running at the state level in positions that determine how election counts are determined.

The possibility is real because so many Republican-leaning legislatures were gerrymandered after the 2010 census, while the Democrats slept. There are 435 House seats up for grabs but due to gerrymandering only 59 are deemed “competitive” by Politico. In states like Wisconsin and Michigan you can’t get rid of the Republican majority; it’s voter-proof.

The possibility is real because the Republicans stacked the U.S. Supreme Court with their loyal lawgivers, and as the Court reconvenes this fall, they will take up “the independent legislature theory” by way of Moore v. Harper, a case out of North Carolina that could allow legislatures to skew election rules, with no judicial oversight. The possibility is real because the Republican Party uses power everywhere it gets it, while the Democrats strike responsible poses and preach moderation and say, “We’re better than that.”

If the normal mechanics of democratic elections are thrown on the scrapheap in 2024, the Republicans will be culpable, but the Democrats will be complicit. The Democratic Party keeps waiting for the Republicans to go too far, assuming it will then reap the benefits. But somehow the party that in its earliest days referred to itself as “the Democracy” has been passive and tentative in defending democracy. They’ve been unwilling to address the structural reasons Republicans hold onto power without majority support from the electorate. The Democrats’ aged leaders have spent their lifetimes focused on getting legislative compromises passed and looking for “business-friendly” microsolutions, thinking they will be rewarded for it. They don’t seem capable of understanding that different times—with a more radicalized, propagandized, and implacable opposition—require different tactics.

That’s the breakfast-table rant, anyway. Progressives, populists, and leftists have been arguing this way for a long time. Yet the Democratic Party elders — and their consultants and big funders — loathe and distrust the progressives, populists, and leftists in their ranks. The argument for a pugnacious party defending democracy and the economic interests of workers, fueled by grassroots organizing energy, goes nowhere.

Extremism and rhetorical incontinence represented the true id — and the long-term future — of the Republican Party. Michael Kazin’s recent study, What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party, gives us a deeper understanding of how difficult it is — and has always been — to move this party. I have not finished Kazin’s book but in the “cheat sheet” given to book reviewers such as myself, the publisher includes these quotes from the book:

“When Democrats made a convincing appeal to the economic interests of the many, they usually celebrated victory at the polls”.

Yet there is so much riding on that word “convincing” that it’s hard to find the explanatory value. What emerges from the story he tells seems to be something more fundamental and perhaps more complicated.

It took a remarkably long time for the Democratic Party to lose the South. FDR’s reelection in 1936 marked the first time most African Americans in the North voted the same way as whites across the South:

“African American districts in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that had never backed a Democratic nominee for president before voted for FDR by a landslide of 70 percent. The ‘party of Lincoln’ has rarely been competitive among Black people in the state again.”

While this transition was occurring, the Democrats were also racking up solid support from union members. Union membership doubled to eight million in the two years after 1936. By the end of WWII, and on through the AFL-CIO merger in 1955, union membership was at its historical peak, with about 35 percent of wage-earners represented. The New Deal had resulted in a Democratic Party that was “a grand coalition of heterogeneous parts.”

How is it possible that the Republican Party has made itself more malicious, conspiratorial, gun-crazy, and cultish – and yet still manages to run neck-and-neck with the Democratic Party?

The long game. It does not inspire confidence that the Democratic Party spent so much time, under Clinton and again under Obama, wholly absorbed in projects to invent a “softer Reaganism”, thinking the voters would reward them for being “smarter” or “nicer” as they sought to end “welfare dependency” and spoke in reasonable, even tones as the “adults in the room.”

Democrats lost the South because Republicans cynically inflamed racism, yes. But many wounds have been self-inflicted, and many treatments shunned. It was in the labor movement where you’d hear the slogan “Black and white, unite and fight!” — yet as Kazin details the Democrats lost interest in supporting unions with better labor laws, pushing for industry-killing trade laws instead. To keep at least a few rural states in the Democratic coalition, the party needed to tap into authentic American economic populism – but that language was horrifying to Democratic funders and consultants.

Not to Republicans who had been running with their manipulated populism for years. From stacking the courts and overturning Roe to enriching the oligarchy and empowering an electoral minority, the right has played the long game and won. It took most of us far too long to fully comprehend that Trump’s presidency represented a qualitative uptick in the determination and capacity of the right to impose minority rule. Forty years of Republican anti-tax, anti-regulatory, anti-government ideology and governance; backlash against the election of the nation’s first Black president; fear of demographic change; the growth of a far-right, all-encompassing media environment; and long-standing, deeply rooted patterns of white and Christian supremacy set the stage for his election.

The struggle in which the world is now enmeshed transcends individual nation-states. It is not so much a “clash of civilizations,” in the sense that Samuel P. Huntington famously framed it, but rather one between cultures – an emerging digital culture different from anything we have known until now, and a culture reacting against all of this. The latter is not simply an ironically global antiglobalist movement. Pace Huntington, it encompasses a wide range of historical cultures – fundamentalist Islam, the Christian traditionalism of nationalist movements across the West, and the Eastern Orthodox authoritarianism of Vladimir Putin, as well as the nonreligious (though similarly sex-obsessed) ideologies of China and North Korea.

In short, 9/11, the Capitol insurrection, China’s suppression of Hong Kong and designs on Taiwan, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine are all expressions of the same global reaction. It is a reaction against liberalism, rationalism, and modernism, exacerbated by the extreme disaggregation, individualism, and relativism the digital revolution has thrust upon our analog world.

But that revolution is equally subversive of Enlightenment culture and everything it has represented: liberalism, individual autonomy, democracy, free markets, rationality, and the essential belief that all of these lead humanity toward not chaos but rather a collective and higher Truth, a Greater Good. As George Packer noted in his 2013 book “The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America” :

“This culture has not been without its fair share of criticism already, and not just from reactionaries: capitalism, for its relentless degradation of non-commercial, non-material, and non-individualist values; liberalism, for its undermining of community, consensus, and constraint; even modern science, for its reductionism and relativism. Today’s increasing alienation, hyper-democracy, intolerance and “bully” culture, abrogation of all authority, collapsing of all categories, digitization and commoditization of everything from human wellbeing to the entire natural world, and the negation of meaning—all raise the question: Are these simply the logical, indeed inevitable, outcomes of scientific rationalism, liberal democracy, and market economies?”

My answer? Yes:

So, what, then, of democracy? It will not survive at least in the form we know: In this brave, new, disaggregating and individuating world, where you can make your own realities and construct your own communities, you do not have to be part of anything with which you disagree. So why should you have to submit to the will of the majority? Soon, you will not: you will simply join a different community, culture, country, or .com (or different ones for different purposes), in which everyone shares your values and identity. This is not democracy or society as we have known them, but it would be highly democratic and social. It would be a world in which we would find a way to satisfy human needs.

It would be a long-term future, in short, of greater prosperity, sustainability, security, freedom, community, and meaning – but not one for the common, greater good. Perish the thought.

Whether we attain that level is not important because we shall not avoid catastrophic collapse, the subject of my book which this essay (somewhat) outlines.

And I leave you with this thought. I have been deep down a rabbit hole for this essay, this book, seeking to apply what I know, what I have read, over these last few years. One key, one kernel, one core takeaway is that (we) as human beings seem on the whole quite poorly equipped by language and its corollary artefacts, entities and systems of ordered cognition to engage or constructively shape the vast and complex political systems we inhabit, that we have created.

There is a mischievous property in all of these information and communication (although not always explicitly technology-inflected) systems of governance and knowledge. Every assertion of control and teleological abbreviation as leverage comes at a cost, the generative ripple of yet more complexity, more disruptive doubt. Analysis functions similarly, one step removed.

The Bill Maher Commentary

Bill Maher, the comedian and host of “Real Time”, has little hope for the future of America if the Republican Party sweeps the midterm elections Tuesday as polls have predicted. In the following video he noes “Democracy is on the ballot and unfortunately it’s going to lose. And once it’s gone, it’s gone. It’s not something you can change your mind about in reverse.”

Many of his usual fans on the left have accused the “Real Time” host and comedian of swaying too far to the right in recent months, criticizing Democrats and “kissing up to” the GOP. But in the “New Rules” segment on his HBO show Friday night, Maher laid on the doom, gloom and, frankly, fear pretty heavily if – or when – the Democrats take a beating in the midterm election just a few days away.

“I know I should probably tell you to vote in what honest to God is really the most important election ever,” he began. “So, OK, yes, you should vote and it should be for the one party that still stands for Democracy’s preservation. But it’s also a waste of breath because anyone who believes that is already voting and anyone who needs to learn that isn’t watching, and no one in America can be persuaded of anything anymore.”

The House hearings over the January 6 Capitol insurrection seem to have changed nobody’s mind, he pointed out. “After all the hearings, the percentage of Americans who thought Trump did nothing wrong went up three points,” he said. “That’s America now. It’s like trying to win an argument in a marriage. Even when you’re right, it still gets you nothing.”

He then laid out his prediction for not just the outcome of the election, but of the days, months and years to follow.

“Republicans will take control of Congress and next year they’ll begin impeaching Biden and never stop. They’ll impeach him for getting out of Afghanistan and getting into Ukraine, for inflation, for recession, for falling off his bike. It won’t matter and it won’t make sense,” Maher said. “But Biden will be a crippled duck when he goes up against the 2024 Trump-Kari Lake ticket,” he said, referring to the former local Phoenix news anchor poised to win election as Arizona governor next week.

“And even if Trump loses, it doesn’t matter,” Maher continued. “This timem he’s not going to take no for an answer because this time he will have behind him the army of election deniers that is being elected in four days.” The host was referring to the almost 300 GOP candidates on the ballot this year “who don’t believe in ballots, and they’ll be the ones writing the rules and monitoring how votes are counted in ‘24.”

“This really is the crossing the Rubicon moment when the election deniers are elected, which is often how countries slide into authoritarianism, not with tanks in the streets, but by electing the people who then have no intention of ever giving it back,” he said. “The Republican up for Wisconsin governor just said if he’s elected, Republicans will never lose another election. This is how it happens. Hitler was elected, so was Mussolini, Putin, Erdogan, Viktor Orban. This is the ‘it can’t happen to us’ moment that’s happening to us right now. We just don’t feel it yet.”

Maher partially blames technology and, yes, Fox News for the spreading of conspiracies and outright lies for the decline in people’s understanding of what a democratic government is supposed to look like – and everything they’ll be losing if it is gone.

“Democracy’s hard. Athens didn’t have to deal with Fox News or the smartphone that made everybody stupid and they only lasted 200 years,” Maher said. “I’d like to say a little farewell to some of the things that really did make America great that now we’re going to lose forever. Like the peaceful transfer of power, the jewel in our crown, that thing that so many other nations couldn’t pull off that we always did. Oh well. The Bill of Rights — when there is no accountability at the ballot box, there are no actual rights.”

It will be an entirely different way of life for many, he said, because “our elections will just be for show like in China and Russian.”

“I wouldn’t count on that one lasting,” he added. “I wouldn’t count on freedom of religion lasting. And the other shock troops of the Trump takeover of the Republican Party are all quasi-religious entities who want a Christian government. Oh, and the FBI might be replaced by an army of Proud Boys under the leadership of Michael Flynn. Even something like pot, will it stay legal? It probably depends on whether Snoop Dogg calls Trump brilliant one day. That’s how things will be decided, not by the rule of law.”

In conclusion, Maher urged everyone to vote. “But I’ve always been a realist. I’m afraid democracy is like the McRib – it’s here now, it’ll be around for a little bit longer, so enjoy it while you can.”

Watch the entire “New Rules” segment below: