Policy is hard, and people will be arguing for years about what the EU’s new twin pieces of new legislation, the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, mean – just as we continue to do with the GDPR.

And now geopolitics has offered the U.S. an opportunity, throwing a spanner in the works.

Stepping back, though, I think you could suggest that there is little or nothing in any of these laws that would create fundamental structural change in the way we experience technology.

28 March 2022 (Berlin, Germany) – Privacy is secondary when it comes to money and power. That’s just how the world works. We just saw it again. Last Friday U.S. President Joe Biden and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced that the EU and the U.S. had struck an agreement in principle on a revamped “Privacy Shield” data transfer agreement. It’s really an “agree to agree” deal. In other words, Biden has forced the EU to compromise in order to reach a deal.

For the last two years it has been “technically” illegal to move any personal data from the EU to the U.S. since EU courts had held that the U.S. did not have “equivalent” data protection laws, in particular to stop U.S. intelligence agencies from looking at data. But data still moves, almost everybody ignoring restrictions. Companies have continued to transfer such information between both regions, and national EU regulators have turned a blind eye.

But most people understood that at a minimum, to be “legal”, moving all data from any cloud service to the EU would be extremely expensive and impractical. And simply be impossible. One example I noted last year in social media: if a German “likes” a New Yorker’s Instagram post, where does that get stored – exactly?

American negotiators sent their European counterparts a new offer last month to secure a revamped Privacy Shield agreement. That’s almost two years after the EU’s top court invalidated a previous legal agreement that allowed everything from social media posts to company payroll to flow freely between two of the world’s largest trading blocs.

But then … Ukraine. U.S. policymaking circles highlighted how the ongoing conflict – and the ability for U.S. intelligence agencies to provide real-time insight to their European counterparts – is a reason why an agreement should be reached, and quickly.

Yes, Brussels and Washington are still at loggerheads over how European citizens’ privacy rights are protected in the U.S., as well as how American intelligence agencies can access foreigners’ data in the name of national security. The talking points will be recognisable to everybody:

• The American side of the debate was that the war in Ukraine shows how fundamental such an agreement is for global security. It highlighted the importance of strong relationships “between like-minded democracies”. And my favorite, the role that intelligence and Big Tech plays in facing very real threats.

• On the European side, policymakers dismissed the link between Privacy Shield and the conflict in Eastern Europe. They said such connections failed to grasp the legal complexities of securing a new transatlantic data transfer pact, which was expected to face immediate challenges from privacy campaigners in Europe’s highest court.

The biggest issue: how to oversee how the U.S. intelligence agencies handle Europeans’ data. The enormous problem: the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling that gave Washington legal cover for keeping documents associated with government surveillance hidden from the public — a key sticking point in the EU-U.S. negotiations. The court in ruled unanimously that the federal government could invoke its state secret privilege, or ability to not disclose material in court on national security grounds, when individuals filed lawsuits against potential illegal surveillance activities.

And the dark side. The underlying problem is that the EU needs security of energy supply and therefore urgently needs to get rid of Russian gas. The Americans have offered to help with that. So it should be no surprise that the Americans are putting pressure on the EU in a quid pro quo not to be so difficult about international data traffic. After all, the Schrems cases are the result of European legislation. And legislation is changeable; you just have to want to. These are EU Court decisions you say? Well, explain to them how the world works. Because I wouldn’t be surprised if the U.S. threatened to stop gas supplies if the EU Court torpedoes the third version of Safe Harbor/PrivacyShield again. Of course, the EU Court has nothing to do with that, but the EU legislator does.

With Putin as its neighbour, the EU has now become the underlying party in US-European relations. Biden knows that and so does von der Leyen. Europe’s quest to rule the world through trade and ethics and tech regulation is now rapidly losing out to the old-fashioned power politics of Russia, China and – yes , the U.S.

For most privacy professionals, Schrems is a compliance problem. But if you have followed my posts over the last 5 years you have “heard” me say that trade conflicts have been fought over our heads for years in which protection of personal data is a serious weapon (yes, data is really the new sand. Not oil. Sand).

The EU has been able to decide many of these discussions in its favor in recent years. Vestager’s digital package was a deal a blow out EU regulatory dominance. But because of European energy dependence on Russia (and soon America), this could change. We should probably prepare for less power for Europe at the negotiating tables. With possibly more balkanization of data and digital services as a result if Europe continues to stand up for its principles. Europe does not have a very good hand to play.

Ah, the reality of regulation

All industries eventually become subject to some law, some regulation, all of varying degrees. They are subject to employment law, accounting law, workplace safety laws and so on. But some industries are big enough and complex enough that they need their own specific rules. There are specific regulatory regimes around food safety, banking, airlines and cars, and many others, and now tech is getting its own regulations. This is mostly, so far, led by the EU and to some extent the UK, partly because of U.S. legislative gridlock but also perhaps because Europe has a culture of regulation where the U.S. has a culture of litigation. So you have the UK with its Online Harms Bill, covering (mostly) content moderation, and the EU is working on the Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA), which of course follow GDPR from a few years ago. These are big, chunky laws with big, chunky penalties – the DSA/DMA can fine you 10% of global revenue – and they are getting very close; the DMA has just been passed from the amendment stage for final approval.

A lot of these laws will simply codify things that most responsible tech companies do anyway – you must look for CSAM (a set of agreements and rules to organise identity and access management, for example), or you must have a way to report security breaches. Here the main challenge is to create the obligation without too much additional cost, or too much entrenchment of existing market structures, and hence too many barriers to competition.

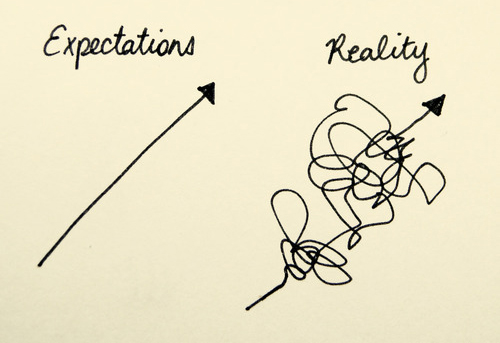

Some of them, meanwhile, continue to ask for things that are physically impossible – for example, the idea that you can have “secure encryption with a back door”. The favourite retort from my techno-mavens is “this is equivalent to asking General Motors to make gasoline that doesn’t burn”. The legislative process is supposed to filter out things like that and generally does, although California’s experience with its “gig worker classification legislation”, intended to class Uber drivers as employees, accidentally banned all freelance work, and shows what happens if the process fails.

But the more interesting cases are those where the law says you must do something that is certainly possible but where it’s not necessarily clear how, or whether that this is a good idea – or, at least, there are significant trade-offs. Almost no one outside Apple (and not many necessarily even inside Apple) supports Apple’s current in-app payment rules, but allowing third-party app stores, or even more, allowing side-loading, would be a major shift in the security and privacy environment on a billion iPhones. These are questions where people have disagreed for a decade, but now, in Europe at least, regulators have picked a side (the extremist side) and Apple won’t have a choice. European iPhones will get more app stores and be less secure – deal with it. Google will have to unbundle its services from Android – deal with it. What does “deal with it” mean, though? It’s all about the detail. How exactly does side-loading work, with what kinds of warnings? How does Airbnb’s appeals process work? What does “consent” mean? Big Tech is already in the planning stages to have different tech and processes available in Europe to avoid all of this.

And the DMA has a great, brand new example of this kind of problem. The one I have used many times in the past is Amendment 127 to the DMA:

Allow any providers of number independent interpersonal communication services [i.e. messaging apps, as opposed to SMS] upon their request and free of charge to interconnect with the gatekeepers number independent interpersonal communication services identified pursuant to Article 3(7) [i.e. big tech companies’ messaging apps]. Interconnection shall be provided under objectively the same conditions and quality that are available or used by the gatekeeper, its subsidiaries or its partners, thus allowing for a functional interaction with these services, while guaranteeing a high level of security and personal data protection

So messaging apps need to interconnect. That sounds good. But what does it mean? Apple knows me by AppleID, a personal email address. Signal knows me by my phone number. Google knows me by a special address I set up to prevent tracking. Facebook doesn’t know me (I do not have an account). You receive a message from WhatsApp user GregBufithis1022. Who is it? Is it me? An attacker? Or someone else with the same name?

Yeah, it certainly sounds it would be relatively straightforward to imagine how iMessage and WhatsApp could be interoperable, but more of a puzzle to work out what it would mean to send a Snap story to WhatsApp – what does the EU think should happen then? And who gets fined if it doesn’t work? iMessage does not have WhatsApp’s groups model, with group owners and permissions; does Apple have to copy WhatsApp’s feature? Will each app need to have two or three different kind of group? If any messaging app is obliged to accept any inbound messages from any other app, then how do you deal with spam or harassment? How do you obey the DSA’s requirements to moderate harmful content if you don’t control the client? These are not protocols – they’re systems.

Of course, there are always questions – it’s always hard – and generally they can be resolved. But all of this needs work from the regulator – you can’t answer this in five lines at para 127. And there are difficult trade-offs here – even though the last line of the paragraph says that you must weaken privacy and security without weakening privacy and security. Apparently you can pass laws against trade-offs. There is also, paradoxically, a conflict between between innovation and competition. The more that you tell companies everything has to be interoperable to enhance competition, the more you’re saying it all has to work the same way, and removing one vector for competition, not enhancing it. Tech regulation is almost always a trade-off between privacy, competition and product – pick two.

One problem that is definitely not easy to solve, by the way, is encryption: we do not today have any settled way to do end-to-end encryption across different networks. A cynic would say that a demand for interoperability is a ban on encryption, by the back door.

The irony of all of this is that a big part of the theoretical model of something like the DMA is to produce one generalised piece of legislation that covers everything that’s a “market” from Airbnb to app stores to web search, so that you don’t have to spend three years doing a detailed study on each question and instead create general principles that apply to any “market”.

This is a chimera – you might as well say you’re going to write a General Automotive Act that covers every question from parking to airbags to cycle lanes. Policy is hard, and people will be arguing about what the DSA and DSM mean for years, just as we are with the GDPR.

Stepping back, though, I think you could suggest that there is little or nothing in any of these laws that would create fundamental structural change in the way we experience technology. There is no path to creating a third smartphone operating system, nor to replacing ad models with subscription, nor to get all of us to switch from Instagram to something else. Some of these rules will make things slightly easier for some companies, most of them will raise costs for new entrants, and many of them will create more low-level degradation of our experience – more equivalents of cookie banners. But meanwhile, TikTok has gone from zero to a billion users even though “competing with Big Tech is impossible!”.

Just a few quick points on DMA since I am on a roll:

• All the key definitions are being left to delegated acts. Why? Put them in now. And the few definitions now in the act are not aligned with other EU laws.

• The DMA focuses exclusively on contestability and fairness and ignores the impact for consumers, such as on safety, privacy, and security and for the growth and innovation potential. So what you have is an increased risk to consumers downloading insecure apps from non-verified sources. You’ve doubled fraud exposure and safe online marketplaces to promote “fairness”. The designation criteria for gatekeepers should be clarified and extended by additional qualitative parameters coherent with the risk of harm.

• Obligations put on the platforms should be clarified. Generally, more guidance should be given to companies on how they could comply with the DMA.

• The DMA could provide better opportunities for regulatory dialogue and the right to defence – helping both the regulator and the regulated platforms to target the problems. This is the way this stuff works in the real world.

POSTSCRIPT

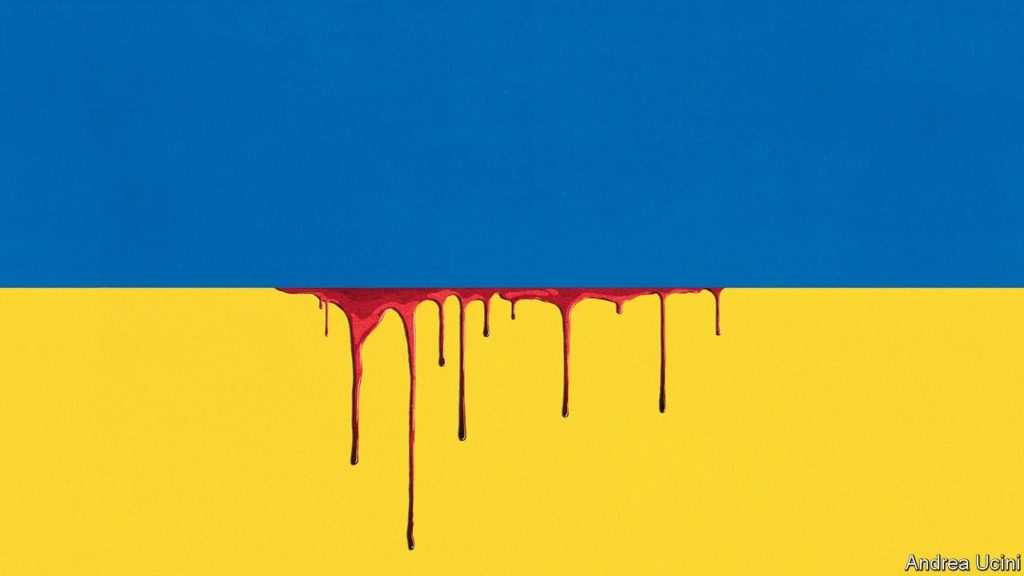

Roman Kushnaryov is a Ukrainian HR specialist, still based in Lviv, Ukraine despite its horrific bombardment. His speciality is finding candidates for application development, custom software development, and mobile application development. He posts on Linkedin and Facebook and he and I have had some conversations. Now he is doing everything he can to find remote work for his friends and clients. Over the weekend he shared the following:

“I hear so much whining on LinkedIn (mostly from Russians) that LinkedIn is for professional posts only. Please look at this footage:

The above is Irpin. A town next to Kyiv, our capital. A place where many professionals built or bought their houses. Houses where they worked during the pandemic. You could see their posts on LinkedIn about their job, about their achievements and promotions.

Now, because of the Russian invasion, they are either killed or had to leave their homes.

So, when you see a post on LinkedIn from someone complaining that it is a professional network, share this video with them. This is now, this is happening, this is the real world. People from Irpin, Bucha, Chernihiv, Kyiv, Hostomel, Sumy, Kharkiv, Kherson, Mariupol, and many other Ukrainian towns and villages would love to go back to posting something about their profession on LinkedIn but they can’t because of the Russian invasion.

We, Ukrainian professionals from LinkedIn, had to join Ukrainian Armed Forces or territory defense or volunteers who support our army, so we can win our country back.

That has now become part of our professional portfolio.

As I noted in an earlier piece in this series, the United States doesn’t have even the vaguest memory of anything like a modern total war. It’s most recent wars were, of course, devastating for many of those who served – but were an outsourced affair that changed daily life for most Americans not one jot. The U.S. is involved in something like half a dozen conflicts at any given time, and most Americans can merrily live their lives without realizing it.

Part of the reason why the European reaction to the Ukraine situation has been so intense, apart from the obvious geographic proximity, is that the collective memory of what the Ukrainians are now enduring lives on in the European mind. Americans just see some unpleasant news in a country far away that most know little about; Europeans see echoes of their own recent history in today’s news and recognize a demon they thought they’d banished forever.

America is fortunate that it can live in “The Matrix”, removed from the reality of the world. It has the luxury of not needing to notice, allowed to go about their lives thinking their usual thoughts and having their usual conversations.

It is a rare thing to live through a moment of huge historical consequence and understand in real time that is what it is. Putin has redrawn the world – but not the way he wanted. At some point hard realities, no matter how unpleasant or unwelcome in America’s comfortably distanced lives, will pierce through.