Munich has always been accused of not quite coming to terms with Hitler’s legacy.

Recent exhibitions demonstrate that the city’s institutions are sensitively reckoning with their fascist pasts.

ABOVE: Hitler leaving Landsberg Prison (40 miles outside Munich). In 1924 he spent only 264 days incarcerated (of a nine year sentence) after being convicted of treason following the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich the previous year. During his imprisonment, Hitler dictated and then wrote his book “Mein Kampf” with assistance from his deputy, Rudolf Hess. Records discovered in 2010 revealed he was given special treatment by the prison’s administration and was allowed 100s of unsupervised visits from followers and staffers, allowing him to build his organisation.

2 December 2021 – The city of Munich became a Nazi stronghold when the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933. The Nazis created the first concentration camp at Dachau, 10 miles northwest of the city. Because of its importance to the rise of Nazism, the Nazis called Munich the Hauptstadt der Bewegung (“Capital of the Movement”). In the postwar chaos after 1918, the Bavarian city and its rowdy beer halls offered the failed Austrian painter and returned soldier an ideal stage and receptive audience for his firebrand politics. Munich was a hotbed of right-wing nationalist opposition to the Weimar Republic, and a logical place for Hitler to co-found his National Socialist Party in 1920.

But for decades after the war the “Bavarian question” always loomed large: Vergangenheitsbewältigung – or “coming to terms with the past”. In those subsequent years, as Munich and other German cities struggled to rebuild their wartime ruins, the daily struggle to survive understandably took precedence over debates on the Nazi era. But once Munich found its feet, critics said the city was less interested than others in exploring the dozen Nazi years. Instead it hitched its historical wagon to the memory of King Ludwig and the historical tradition that went before Hitler.

Only a few Nazi buildings were torn down after the war, stripped of swastikas and eagles and but still in use today. Some argue that, given the shortage of buildings in postwar days, this was a pragmatic step similar to that in other German cities. But historian Gavriel Rosenfeld, in his book “Munich and Memory”, argues the normalisation of Nazi buildings in Munich was emblematic of the prevailing desire to forget the war and, more specifically, the city’s responsibility for nurturing the political movement that produced the wartime destruction in the first place.

But Munich’s history was not my primary reason for this trip (coming shortly before my current trip in the U.S.) It was to visit Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp, opened in 1933, shortly after Hitler became chancellor of Germany. Dachau was initially a camp for political prisoners, the able-bodied prisoners used as slave labor to manufacture weapons and other materials for Germany’s war efforts. However, it eventually evolved into a death camp where countless thousands of Jews died from malnutrition, disease and overwork or were executed. In addition to Jews, the camp’s prisoners included members of other groups Hitler considered unfit for the new Germany, including artists, intellectuals, the physically and mentally handicapped and homosexuals. It was also the training center for SS concentration camp guards, and the camp’s organization and routine became the model for all Nazi concentration camps. It was also home to the Nazis’ most notorious medical experiments.

It was after our two days at Dachau that Zoë Meier, my German staffer assisting in this production, suggested I take in some changes in the Munich art world to see Vergangenheitsbewältigung at closer hand.

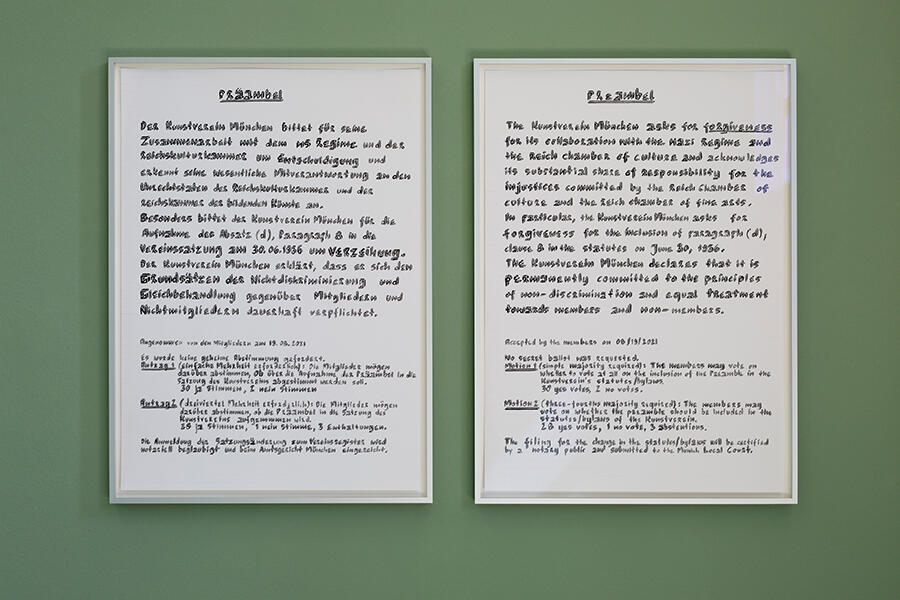

One thing I have learned trolling scores of Nazi and Holocaust archives is that the power of the archive lies not only in its documentation of events that ought to be remembered but also in the records it holds of histories that some might otherwise prefer to forget. While researching her recent show entitled “No River to Cross” (see below) at the Kunstverein München art association in Munich, the artist Bea Schlingelhoff unearthed a document from 1936 which stated that non-Aryans could not become members of the art association. Following the formation of the Reich Chamber of Culture in 1933, which promoted Nazi ideals, amendments like this were common across Germany in 1000s of documents, and in 1000s of situations. Arguably the nadir of this cultural oppression was the “Degenerate Art’”exhibition of 1937, one iteration of which was held in the building where Kunstverein München is now located.

For ‘No River to Cross’, Schlingelhoff filled the entire space with differently sized, dark-green rectangles painted across the gallery’s bright-green walls:

These rectangles, the exhibition text explains, are placeholders for the 650 modernist artworks seized by the Nazis from 32 German museums, which were shown and defamed here during the “Degenerate Art” exhibition. By painting the squares in a darker color, the artist also echoes the gaps which appeared on the walls of the pillaged museums.

While many buildings in the city have historical ties to the fascist regime, Kunstverein München bore no marker of its own affiliation until Schlingelhoff installed four permanent plaques on the facade, naming the only female artists that were included in the “Degenerate Art” show: Maria Caspar-Filser, Jacoba van Heemskerck, Marg Moll and Emy Roeder:

Such an exhibit, such actions were unheard of in Munich.The event sold out.

Zoë told me that as with many of Schlingelhoff’s works, the project’s significance extends beyond the dates of the exhibition. Prior to the show, Schlingelhoff also proposed a change to the Kunstverein’s statutes, in which the institution “asks for forgiveness for its collaboration with the Nazi regime and acknowledges its substantial share of responsibility for the injustices committed by the Reich Chamber of Culture”. It passed on a majority vote.

More impressive, the recently founded Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism is another successful example of a Munich institution acknowledging the importance of commemoration. It serves as a locus of remembrance in a city long known as the “capital of repressed memory”. Featuring archival photographs, objects, documents and short films, the museum’s permanent exhibition gives a chronological account of Munich’s role as the city in which the Nazi Party was founded during the Weimar Republic, documenting its reign of terror, the rise of the resistance, the war years and the postwar response. Located on the site of the former Nazi Party headquarters near Königsplatz, which served as an arena for militaristic propaganda rallies, the museum is surrounded by the city’s haunting past. Next to the new building lies a weathered plinth: the sole remains of a memorial dedicated to those who died during the failed Nazi putsch of November 1923.

It also hosted the landmark exhibition “Tell Me about Yesterday Tomorrow” which placed works by more than 30 contemporary artists in dialogue with the museum’s permanent collection, underscoring the complex relationship between historic atrocities and the current rise of the alt-right. Last month the museum permanently installed a work called Memory Loops, an audio work comprising 300 German and 175 English tracks based on transcriptions of historic and recent accounts by victims of the Nazi regime in Munich. On the project’s website, visitors can listen to the different stories by clicking on a map of the city. Conceived as a virtual monument, the work provides a space in which Holocaust victims and their families can commemorate their losses without having to visit Germany again.

And lastly, originally founded as Haus der Deutschen Kunst in 1937, the museum Hitler wanted to showcase German art aligned with Nazi politics and ideals, Haus der Kunst has arguably the strongest connection of any cultural institution in Germany to fascism. The museum has addressed its past in a number of ways, including decades of public debate as to whether the building should be demolished entirely. In 1992, however, the state of Bavaria voted to preserve the institution as a foundation, enabling a series of directors to develop considered formats that constantly challenge Haus der Kunst’s past by way of the museum and city’s recollection and reclamation – and recognition of its horrors.

POSTSCRIPT

As the city where the Nazi Party was founded in 1919 and which Adolf Hitler called the “capital of the movement”, Munich’s links with the terror regime are more obvious than anywhere else in Germany, explaining why the museums feel the responsibility to address this history. However, as contemporary witnesses to the Second World War steadily diminish while racist and anti-Semitic tendencies are on the rise throughout Germany, I hope that these sensitive responses to the country’s dark past, which are more important than ever, can soon be witnessed elsewhere too.

Fostering a culture of remembrance is crucial to the future of our democracies – especially now as autocracy is on the march across Europe, and the world. It creates awareness not only of the historical conditions that have led to exclusion, degradation and destruction, but also of our responsibility for ensuring that these processes – created and influenced by people – do not repeat themselves. Although my pessimistic, cynical core – as it gazes across the globe – sees this as a lost cause. However I can say that seeing these art exhibits does make things come together in unexpected and productive ways, especially for this blog and video series.

But it is difficult. As I sat in the Dachau concentration camp memorial site (without my film crew, just quietly watching and listening to people) I captured a recurring impression: visitors approaching the memorial, using their mobile phones to take photographs that will soon be forgotten in the cloud. It highlights the difficulty of keeping remembrance alive, not allowing historic atrocities to be forgotten.

I will return to this theme next year in another supplemental video to my main film (I am assembling those supplemental videos here). As holocaust remembrance passes through that critical juncture, the inevitable passing of eyewitnesses to disaster, it disperses into every corner of cultural representation. The emergence of “holocaust tourism” is symptomatic of that dispersal. The diffusion of holocaust memory into popular forms of remembrance of which tourism is only one part exceeds any simple pilgrim tourist or concentration camp theme park binary.

I entered this project, this discussion as a bit of an outsider but with almost 15 years experience in war crimes investigations, mostly the Yugoslavian war crimes tribunals. Plus I had 12 years work and training in the field of video and film production. So I know that Holocaust remembrance must be approached simultaneously in epistemic, logical and ethical choices. The question of how to represent the Holocaust through various media and disciplinary tools unavoidably engages with an ethics of representation. Holocaust museums, memorial sites and art exhibits must always negotiate the boundaries between knowledge seeking and voyeurism.