24 June 2021 – So an army of executives, lobbyists, and more than a dozen groups paid by Big Tech have marched into Washington, DC to try and head off bipartisan support for several bills meant to undo the dominance of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. I summarised those bills in last week’s edition of BONG!

Obviously U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office leaked information about this army as part of the PR effort against the tech companies. I thought the tech firms capable of better on the PR front, though I think this will all take the normal lobbying route: behind closed doors, at lunches and dinner meetings.

As I have noted, the 2020 Congressional report that resulted from all of those tech antitrust hearings were … to be charitable … very rushed, with great chunks of advocacy pasted in without any scrutiny, and with significant errors of fact every few pages (the report is 450+ pages and a very long slog; it’s a dirty job but somebody had to do it). Perhaps the worst example (as pointed out by many pundits who joined the slog) was the claim that tech startup creation has “sharply declined” in the last decade. This is an important claim, and if it was true we would obviously need broad and urgent intervention. But in fact, it was based on a data set that ended in 2011: both nine years out of data and just at the end of the financial crisis. Most of us in tech can agree on very little, but I posit everyone would agree we’re in the hottest market for tech startup creation in history. Every available data point, every relevant data point will tell you that tech startup creation has actually risen by three to four times the last decade. There are scores of other errors in that report but let’s move on.

And so this report has been followed by the proposed tech antitrust bills published last week. Given the background, and the current US political environment, they are aggressive. However, like the report, they contain a mix of real concerns, good ideas, and some pretty questionable logic. A hopeless mess, but looking at it all through a political prism one assumes three of the four main bills will die so that a single main bill can go through with bipartisan support. And given the current thunder, it sounds like the U.S. Congress could successfully kneecap all their tech companies in the process. I don’t think Big Tech can wait for divisions and fighting among lawmakers to kill the legislation (the classic strategy). Because while it is not illogical to bet that Congress won’t get its act together, the bits that would force companies to pull apart their businesses are existential threats to Big Tech. The companies have to fight them.

There are, of course, a myriad of issues. I want to focus on just two, which are the main focus of all this legislation: (1) competition and (2) a definition of data. This later point will bring me to the real culprits (not Big Tech) destroying any notion of data privacy.

COMPETITION

The legislation is framed to declare “if you own a platform you can’t compete on it”. So Apple or Google should not have any products or features that compete with companies on their platforms. Sounds pretty clear, yes? But what if I want to sell a camera app for your iPhone? OK, so Apple can’t include a camera app – or a clock, or an email app, or indeed a user interface or a file system. An Android phone has its own TCP/IP stack (in the 90s Windows did not, and you had to buy one), but other people would like to sell you that if it wasn’t there, so that’s a clear conflict of interest and has to go.

That shows you the very basic misunderstanding at play here – you can’t ban a platform from having “any” feature, service or product that someone else might want to make, because that describes literally every single thing that a platform does. There is, to repeat, a very real problem here. This was the whole Microsoft/Netscape case. You can certainly carve out specific issues, such as Apple Music, or private label on Amazon. But you’ll need to spend a lot more time thinking about how this stuff works and what the word “platform” really means, because this law wouldn’t just ban Apple Music and Google Maps – it would ban iOS and Android.

This is the “bundling problem” that many have written about. This is the centre of today’s argument about what Apple and Google include in their smartphone operating systems, and what Google includes in “search”, and it was the argument 20 years ago around whether and how Microsoft should include a web browser in Windows.

If a company has market dominance, and it adds a feature to its product that is someone else’s entire business, this is inherently unfair. But life is unfair – so does it follow that it’s bad, and that we should we do something about it, and if so, what? People sometimes argue that this is all obvious and easy. Some things are “clearly” essential features (for example, brakes on a car) and some are “clearly” optional, or at least substitutable (a web browser). But this is a fuzzy definition, and changes over time. Turn signals were optional once, and in the mid 1990s PCs didn’t come with a TCP/IP stack. That was a separate product you could buy. Microsoft (and Apple) added one, and that became an anti-trust question – people proposed very seriously that this required intervention and that Microsoft should offer a choice for your network stack, and your file system, and indeed everything on top of the kernel.

Fun fact for you tech historians: in the 1980s, if you installed a word processor or spreadsheet program on your PC, they wouldn’t come with word counts, footnotes or charts. You couldn’t put a comment in a cell. You couldn’t even print in landscape. Those were all separate products from separate companies that you’d have to go out and buy for $50 or $100 each. So, readers: are those now “essential” or “optional”?

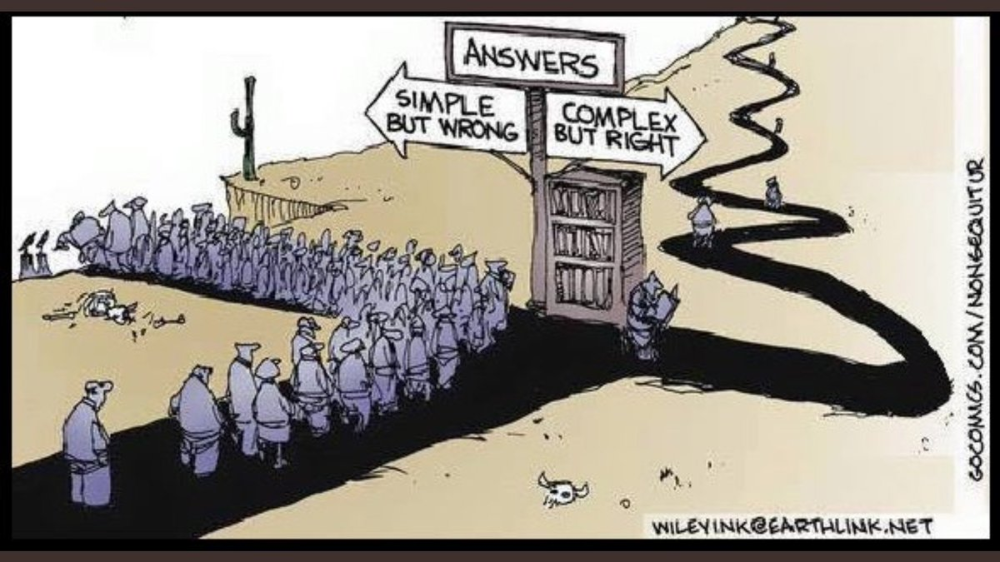

There’s no question that there are business practices all over large tech companies that are bad for competition and should be regulated. This is all coming. However, there are also business practices that are bad for individual competitors but good for the consumer and often indeed good for broader competition. And more fundamentally, there are many decisions that are deeply bound up in trade-offs between the product, privacy, competition, ease of use, profitability, innovation, portability and many other things. If you want to solve the problems, you need to understand why they exist and accept that there will be complexity. We understand that education policy, energy policy or healthcare policy are complicated and full of trade-offs, and that the only people who think it’s simple and easy have their fingers in their ears. Unfortunately, those people wrote some of these bills.

DATA

Let’s start with a given: no company wants to make it easy for you to switch to a competitor, and many regulators are exploring data portability requirements of some kind, from making it easy to export your photos from Facebook, to moving business operations data between enterprise software tools. So one of these bills would require covered platforms to make APIs to let you export your data to another tool in some reasonably standardised way, and give the FTC a mandate to regulate that.

But what is “data”? The legislation provides no definition. Just three quick points:

– If you have spent any time coding or any time learning about the pipes, wires and tunes that make up the internet then you know much of this “data” is very specific to a given software company’s product and infrastructure (and its relation to millions of other users). The practical value to anyone else might be quite limited. Two competing products might create data from customer inputs in unusably differently ways. That’s how markets work – something apparently unknown to members or Congress and their staffers.

– More importantly, who owns that “data”, exactly? If I “like” your Instagram photo, is that “like” my data or yours? How much of “your” data is yours to export? And just how will this work? Well, we just do not know. The bill that covers this crucial area is a staggering … 15 pages long. It punts all the questions to the FTC, which is supposed to just work this all out. So we have a law that says you must make X portable, without defining X, but no worries because the regulator will figure it out. This looks like another great “Lawyer Relief Act”. Lawyers across the U.S. must be salivating.

– But the most important kind of data is not addressed: network effects. If I want to compete with Instagram, I don’t just need your photos – I need your entire social graph and all your friends activity. Well, listen, sweetheart, you’re my friend but that’s MY damn data and not yours to give. So if I want to compete with Google search, I don’t just need your search history. I need raw search and click data for millions of users which I’ll get … where? Oh surely Google will provide it. That’s where the real competitive value of data lies, and that’s not addressed here at all.

There is an entirely new set of data plumbing in the world

I suppose the big take-away in what I have outlined above is that the harsh glare of scrutiny on big technology giants might force them to tweak their business operations a bit (more or less). But I suppose they’ll fight, gnaw and bend because they realize how much of their present and future business depends on both keeping the regulators at bay, and keeping the folks that want their services happy.

But data and privacy? Hoo, boy. That’s another issue and that’s going to be a tough road. You are talking about an industry that has turned user data into money via pixels for practically all of its life. And right now the entire framework, where user data is beamed into the cloud and thence into the greedy maw of optimization code, is being utterly re-architected. This is a generational change whose ramifications extend way beyond mere advertising: everything from your physical movements to your health data to your behavior will be subject to an entirely new set of data plumbing.

I’ve been writing about this new set of data plumbing, and readers who follow “Ad Age” or “AdvertisingWeek” (or attend any of their webcasts and other programs) know this as well. Especially if you attend the annual Cannes advertising conference (or to give it its full honorific, the “Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity”). It’s been running all of this week (virtual, alas). Cannes Lions is what I like to call “The Conference of the World’s Attention Merchants”. Because over the last decade the festival has evolved to include not only more brand clients but also, due to media fragmentation, an expansion into tech companies, social media platforms, consultancies, entertainment and media companies — essentially the entire attention ecosystem. It’s why over the years full sessions have been developed to discuss all of the legal and regulatory aspects of data privacy and databases and data silos which have included sessions on the GDPR plus a myriad of other data privacy “issues” (and how to get around them).

But the real data privacy devils … the companies few pay attention to … are the many smaller and mid-sized companies that most of us have never heard about. Whether it is app developers surreptitiously selling information to third parties, data breaches at retailers (and their digital platforms), or data-brokers with security systems that have more holes than Swiss cheese, these companies will continue to be the cause of most headaches in our digital lives. And they are the group more likely to take liberties with data and privacy.

The best example is the story that surfaced last week (I am sure you saw it) about the electric utilities resetting the smart thermostats inside residential homes in Texas in response to the rising demand for electricity due to record-breaking heat. This story is a harbinger of our future: what at first seems like some minor convenience and even a seemingly good deal becomes a major problem for those who don’t spend time reading the complicated terms of service documents — which is to say, just about everyone. In this case, if a customer signed up for an offering called “Smart Savers Texas” from a company called EnergyHub (which is owned by Alarm.com, a seller of security services), they could be entered into a sweepstakes. But in exchange, they gave permission to EnergyHub to control their thermostats during periods of peak or extreme demand.

This is only one, small part of that new data plumbing reset. Yeah, we dread the future controlled by big technology companies. HA! Child’s play. We ultimately suffer most at the hands of what I call “non-technology” companies that now have access to our private data and control over our lives. And at the top of the list are companies that have always been hostile to their customers: telephone companies, electric utilities, insurance companies, for-profit hospital systems, big airlines, and other such organizations. They will only use “smart data” to amplify their past bad behavior.

Dark patterns (covered in exquisite detail here and here) around offers like “Smart Savers Texas” make it virtually impossible for you and me to really discern what we might be signing up for. After all, no one sifts through the pages-long “Terms of Service” agreements. And I certainly don’t mean to pick on this one company – this “unclear” behavior is part of the entire digital ecosystem. Try getting out from under a contract at a health club or canceling your subscription to The New York Times. Good luck.

In this digital age, these seemingly simple tasks have only gotten harder. What happened in Texas is among a rapidly growing list of incidents that make many pause about embracing the “Smart Home”. The safety of our “connected devices” is increasingly unclear, a mantra I have drummed repeatedly. I have little trust in Amazon’s ability to police its digital shelves. What if the device we are buying is fake or is sending data surreptitiously to an overseas destination? There have been scores of stories about seemingly innocuous apps that collect personal data and sell it to anyone willing to pay. And that is just the tip of the iceberg. It is increasingly important to pause and consider: is cheap really cheap, or is there a bigger price to pay in the long term?

Apple has introduced AppTrackingTransparency (ATT), which will force apps to seek permission to track us and our activity across apps. But that’s just Apple’s opening salvo to grab a piece of the advertising market which it has failed to gain in several previous feeble attempts. And it doesn’t do enough. It can’t. That would hurt Apple. It doesn’t do anything about “first-party” tracking, or an app tracking your behavior on that app itself. Moreover, ATT is prone to “notification fatigue” as users become so accustomed to seeing it that they just click through it without considering the choice. And, just like any other tracker-blocking initiative, ATT may set off a new round in the cat-and-mouse game between trackers and those who wish to limit them. There are already ATT work-arounds.

But that’s the challenge. The pressure of protecting your digital sanctity is falling on consumers, not those who profit from it. Even Apple’s efforts shift the workload to ordinary people, and many of us are just not equipped to handle the cognitive load or don’t understand the impact. It is a point I have raised before: the technology industry played the regulators for suckers pertaining to an individual’s rights on how data is collected and used. The implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies did turn it around and they know it is too late to impose that proper structure so they will make sure any new laws that seek to redress that issue work in their favor. Regulators seem happy so long as the “Terms of Service” explain what companies would do with your data. And not in plain language, but in opaque legalese.

Ah, the digital world. The creators of this wonderful technical infrastructure we live in are certainly under social and legal pressure to comply with certain expectations, but those expectations can be difficult to translate into computational and business and social logics. So it requires a healthy interdisciplinary team of legal scholars, business mavens, computer scientists, cognitive scientists, and tech geeks to understand data privacy. Very few technology conferences do that because their purpose is merely to sell services and products to show you how to “comply”, not explain how the real world works. It’s best to leave them in “The Matrix”.

And “data protection”? It’s just not possible. Data is in perpetual motion, swirling around us, only sometimes touching down long enough for us to make any sense of them. We use data, these numbers, as signs to navigate the world, relying on them to tell us where traffic is worst and what things cost and what are friends thinking and what our friends are doing, or placing an Amazon order and letting Amazon “logistic” the delivery of the package, or getting our mobile photo albums in order, or checking how close that sushi restaurant is, or what hotel is … oh, etc., etc., etc.

And because we do this, data has become a crucial part of our infrastructure, enabling commercial and social interactions. Rather than just tell us about the world, data acts in the world. Because data is both representation and infrastructure, sign and system. As the brilliant media theorist Wendy Chun puts it, data “puts in place the world it discovers”.

Restrict it? Protect it? We live in a massively intermediated, platform-based environment, with endless network effects, commercial layers, and inference data points. The ship has sailed.

One Reply to “The big technology giants and antitrust posturing. Plus, the data privacy devils you don’t know.”