This is a short series not so much about Amazon, Facebook and Google themselves, but rather the America that has fallen into those companies’ lengthening shadows

PART I

Amazon is a country, and we are all its citizens

PART II

The new/not new Facebook leak

PART III

Google changes patent law

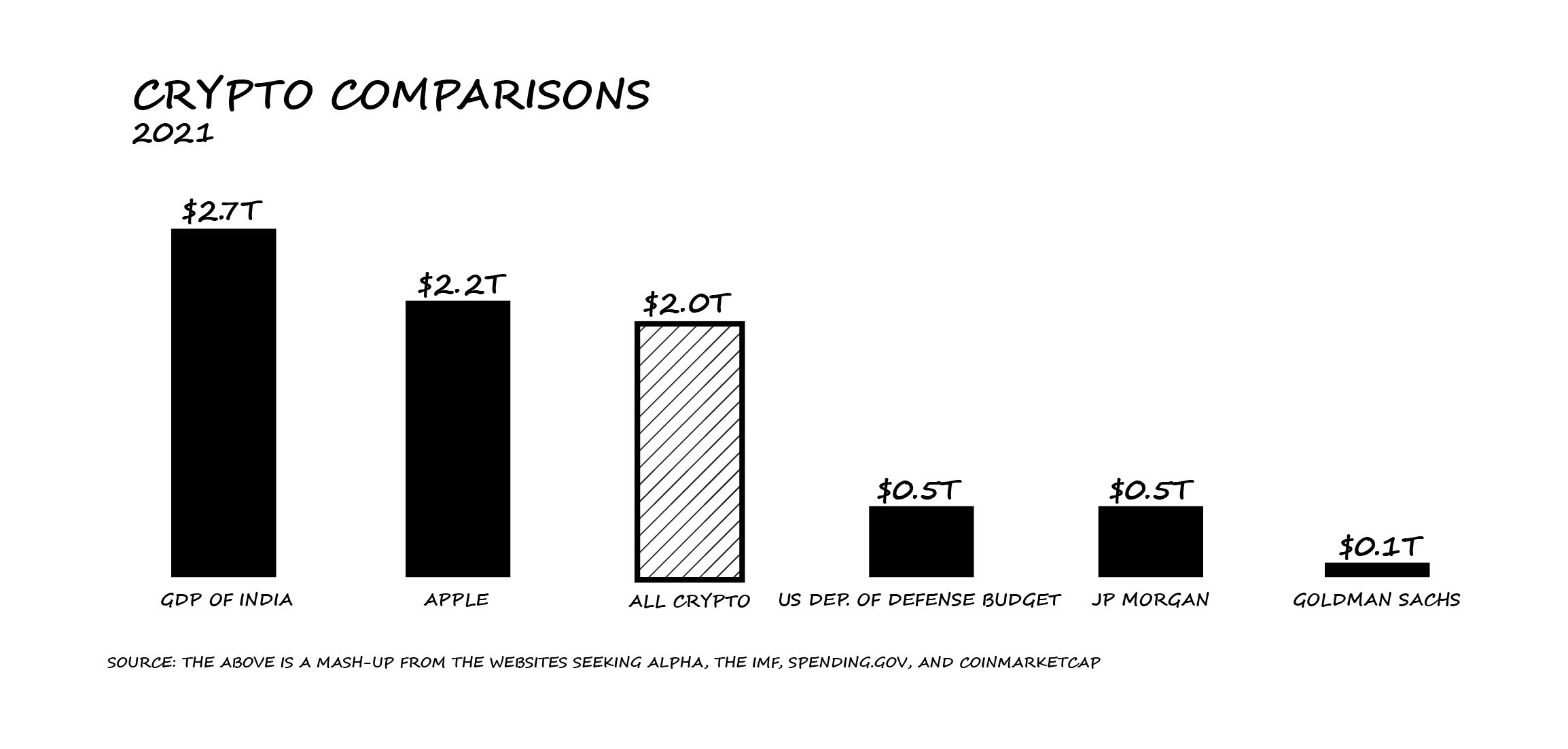

13 April 2021 – Any firm that approaches $1T in value (or exceeds it) has tapped into a basic human instinct. Consuming, signalling, loving, and praying have been the fuel of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google’s ascents, respectively. That the crypto asset class universe has reached $2T taps into two other attributes we instinctively pursue: trust and scarcity. For comparison purposes:

We live in a time where new forms of power have emerged, where social and digital media platforms have been leveraged to reconfigure every conceivable landscape. It is a power shift, really. A power shift from the ownership of the means of production, which defined the politics of the 20th century, to the ownership of the production of meaning. The three “Rs” of the platformed exponential age we live in are new rules, new rights, and new regimes.

In my blog posts I often quote Philip Agre, especially his pioneering article from 1994 titled Surveillance and Capture which is about the way computing systems and networks “capture” data. I love the word “capture”, an implication of a measure of violence as these systems force their environment (us) into the modus of data-engines. He predicted that we’d see a permanent translation of the flux of life into machine readable bits and bytes. And without using the word “platform” but in every sense of the word meaning platform, he said this was all due to our growing reliance on data-driven decision systems, systems “that would need ever more data as we move into cyberphysical systems. It will completely overhaul our existing information infrastructures, social structures and political structures – our thirst for data will have no end”.

And it raises one of the things I detest about the Internet and how it has changed our thinking – the inexorable disappearance of retrospection and reminiscence from our digital lives. Our lives are increasingly lived in the present, completely detached even from the most recent of the pasts. And yet we have this enormous global information exchange at our disposal. So much of what we are experiencing now, often considered as “new”, has been addressed in detail in the past. Besides Agre, Nicholas Negroponte and his book “Being Digital”, originally published in January 1995, jumps to mind. His book provides a general history of several digital media technologies, many that Negroponte himself was directly involved in developing. He said “humanity is inevitably headed towards a future where everything that can will be digitalized (be it newspapers, entertainment, or sex) because we’ll get better at controlling those unwieldy atoms, though a lot it will not be in a good way”. He introduced the concept of a virtual daily newspaper (“customized for an individual’s tastes”), he predicted the advent of web feeds, personal web portals and blogs, the development of “mobile communications in your pocket”, and that “touch-screen technology would become a dominant interface with so many uses”.

Even better is Jacques Ellul, the French philosopher and sociologist who had a lifelong concern with what he called “technique” and published three seminal works on the role of technology in the contemporary world. In 1954 he published the first of those works where he detailed his thoughts on the increasing power and concentration of vast structures, both physical (the factory, the city) and organizational (the State, corporations, finance) that would eventually constrain us to live in a world that is “no longer fit for mankind”. We will be unable to control these structures, we will be deprived of real freedom yet given a contrived element of freedom but the result will be that technology will “depersonalize the nature of our modern daily life”. I recently (finally) finished all three works and they need their own post.

I’ll continue this “Big Picture” view at the end of this series but right now a few words on the “WTF?!” week we just had with Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

PART I

Amazon is a country, and we are all its citizens

At the turn of the 20th century, the vast steel works at Sparrows Point outside Baltimore, Maryland paid poverty wages and was so dangerous that it had its own trolley car to carry dead workers to the city’s cemeteries. In the 1930s, when unions made a concerted push to organize, owner Bethlehem Steel fought back hard. “Outsiders have not been necessary in the past,” one of the company’s manifestos urged. “Nothing has happened to make them necessary now.” If you’ve read the history of the labor movement in the U.S. you know this story, and you know it was replicated hundreds if not thousands of times across the country.

What you might not know is that, today, an Amazon warehouse stands on that very spot where the steel works once stood (Amazon received massive tax breaks from the city and the state to build the warehouse). And the online retail giant, like Bethlehem Steel before it, finds itself trying to fend off unions. The recent unionization vote at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama became the most important fight for the American labor movement in decades. Amazon launched a website warning its Alabama staff that with a union involved, it “won’t be easy to be as helpful and social with each other”.

Ironically, in his book about Amazon titled “Fullfillment”, Alec MacGillis tells the story of Bill Bodani who worked for that Bethlehem Steel plant at Sparrows Point I noted above. Unionization did bring higher wages and better conditions for the steelworkers. But then the plant closed sending 10,000 out of work. Years later Bodani got a job – at the exact same spot to work for Amazon. But for less than half the pay, in a job where he didn’t always have time to go to the bathroom.

Amazon repeated the method in Dayton, Ohio after NCR, a major manufacturer of ATMs, and two other major manufacturers, closed up shop and thousands lost their jobs. Amazon raced into the Dayton area to hoover up the remnants of what was once the Silicon Valley of the industrial age – receiving inducements worth over $18 million a year from a city and state desperate for employers. And the employees? They were offered $10 an hour – “the same I was making at a pizza shop almost a decade earlier” said one ex-Amazon employee.

Last week Amazon won that Alabama vote by a sizeable margin, defeating the union. But if you read the Facebook feeds and Twitter feeds of those who were for the union as well as independent observers (which I did for this series) you know that fraud and obfuscation ruled supreme:

• there was a real fear among many employees that they were going to lose their jobs if they voted for the union, and that’s because they felt that Amazon knew everything they were doing, and even how they were voting

• Amazon got a mailbox installed on the Alabama property and insisted that people vote at that box. Employees said the mailbox made it seem as if Amazon itself would directly see the ballots – a move that could deter employees from voting. Plus they put anti-union posters in the bathroom stalls.

• Amazon lied to people about when they needed to turn in their ballots. They told people they had to get their ballots in by March 1st, even though the deadline was March 29th, so many employees did not vote (2,200 voted out of 6,000+ total employees). The assumption was they were they doing that because they didn’t want them to have the opportunity to engage with the union after having attended mandatory captive audience meetings.

The list goes on and the union filed a long series of objections to Amazon’s “egregious and illegal” anti-union tactics with the National Labor Relations Board.

But I should also note many employees said they didn’t need convincing by Amazon and were against unionizing from the start. Amazon pointed to its minimum wage of $15 an hour, double the state’s minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, which is also the federal minimum. The company also highlighted its healthcare and retirement benefits. Workers said they were wary of the cost of union dues and not persuaded that the union would be able to add significantly to their pay or improve benefits. And Alabama isn’t the best place to try to organize, anyway. It has a terrible record for progressive anything and Amazon jobs are easily the best in the area (which doesn’t say a whole lot about what else is available).

If that is what employees really wanted, so be it, but Amazon was basically violating Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (which governs what employers can/cannot do) left, right, center and every other conceivable direction, so it’s kind of hard to tell how many people were swayed by “informational” sessions that were mandatory. Union blocking and busting are rife throughout American businesses and are rarely punished in a meaningful way. We’ll see if this goes anywhere.

Reality? Amazon has been “improving efficiency” by instituting various forms of automation, reducing is warehouse workforce at each of its location by, on average, 16%. Best not to have a union to protect that mob.

Perhaps worse was the story that surfaced during the vote about Amazon workers forced to pee in water bottles because of the way Amazon robotically tracks employee work times and fires its laborers. The main point is that a large, essentially unregulated company creates working conditions which deny employees the right to deal with bodily functions – and Amazon’s mendacious behavior to explain it. Amazon suggested the whole “pee bottle thing” is simply a regrettable status quo, pointing out a handful of times when other companies’ delivery drivers were also caught peeing in bottles, as well as embedding a handful of random comments on Twitter that happen to support Amazon’s views. You can almost hear Jeff Bezos saying “Why aren’t these people blaming UPS and FedEx? Let’s get more people thinking about them instead.” Ah, the ethical posture of exploitation. The U.S. makes a big deal about China’s alleged exploitation of ethnic groups, yet seems okay with the Amazon and other U.S. entities’ behavior. Interesting or hypocrisy?

However, there is more at work here than a union vote and pissing in a bottle. Amazon is perhaps the best example of how America has fallen in the company’s lengthening shadow. Amazon must be examined through the lens of the geography of inequality, from booming cities such as Seattle to ailing ones such as Baltimore. As Amazon has grown before our eyes, so did those fissures that it had been helping to create all along. All those back rooms where officials quietly agreed to tax incentives for Amazon to build warehouses. The coronavirus pandemic has swelled Amazon’s profits and lengthened its shadow still further.

And, oh, the knock-on effects. The Washington Post had a series on the effects of the shut-down of the Bethlehem Steel plant in Baltimore. Two companies demolish scores of unwanted houses in Baltimore and sell the bricks to the developers of staggeringly expensive studio flats in Washington, DC. The great paradox gallops onward: the spread of blight and abandonment in one city, the spread of congestion and exclusion in another only an hour away. One city rushing to demolish three-storey row houses that would cost $1m in the other down the road.

Plus Amazon’s relationship to politics and power. All those anonymous rooms where officials quietly agree to tax incentives for Amazon to put warehouses in their districts. And the spectacle that ensued when Amazon announced it was looking to open a second headquarters, deliberately sparking a desperate battle between cities to woo it (one Atlanta suburb even offered to rename itself “Amazon”). Only later would we find out that Amazon had already chosen the two cities before the “contest” even began. But by throwing out a “tender” that required a most detailed questionnaire the company collected reams of data from 1000s of cities: general demographics, age groups, educational attainment, foreign-born workers, race and ethnicity, school enrollments, etc.

It’s bloody brilliant. The company’s approach to tax avoidance is a veritable Swiss Army knife, with an implement to wield against every possible government tab. Amazon has funneled profits through Luxembourg and avoided paying the U.S. government $1.5 billion. (That stat comes courtesy of an internal IRS report, so it’s not as if the auditors are unaware). The company uses local resources, like emergency medical services and fire departments, but does so essentially for free, because states exempt the company from paying property taxes. And there’s the rub: when Amazon created a second headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, in an already prohibitively expensive housing market, they made a $3 million donation toward affordable housing and then stated that it was up to government to provide solutions, not private citizens and corporations. Left unmentioned was that government at all levels had become less able to carry out its functions as a result of the tax avoidances the company had perfected. And that vaunted “$15 minimum wage hike” it loves to flaunt? Hundreds of thousands of delivery contractors were left out of that raise.

But Amazon is unusual in the range of things that it does. A revealing story in The New York Times about Baltimore and Amazon shows how the city was enmeshed in Amazon from top to bottom: airplanes take Amazon’s shipping, which has eclipsed that of UPS and FedEx put together; workers rush through timed shifts in the local warehouses; players for the Ravens (the National Football team franchise based in Baltimore) have chips embedded in their uniforms that stream their movements to Amazon Web Services; the local government and university are now handling procurement through Amazon Business.

And continuing, Amazon’s huge power comes not just from its wealth, but from its ability to spy on competing products that vendors sell through its site, plus the fact that it hosts some of its own rivals on Amazon Web Services.

Some final thoughts on Amazon

I often think about the habits I perpetrate that stand in contradiction to my values yet I find myself unable to shake. I eat meat when I adore animals; I’m addicted to the dopamine rush of social media yet hate how it hijacks my brain; I rely on Amazon when I know full well the havoc it wreaks. I still read 3-4 books a month and rely on Amazon – so my Amazon dependence has certainly moved into my top problematic slot.

Amazon is the lens through which to understand the growing gulf between rich and poor in America. There is the extreme wealth inequality encapsulated by Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos’s outlandish personal fortune and the modest wages of the vast preponderance of its employees. There is the nature of the work most of them engage in: rudimentary and isolating, out on the edge of town, often with unreliable hours and schedules. It recasts their daily life at its most elemental level.

Bezos? His personal wealth has grown by about $70 billion during the pandemic, to bring his total wealth to $189 billion, a number so large that I find it hard to picture. Apparently other people struggle with this, too. One popular YouTube video asks viewers to imagine his wealth as almost 11 million Toyota Corollas, or as working for $8,000 an hour since the birth of Christ until now (you would still not have as much money as Bezos). After one stock surge in July, Bezos’s wealth increased by $13 billion in one day, a sum close to the GDP of Madagascar with its 26 million people. Nine months into 2020, and six months into the pandemic, Amazon surpassed its 2019 earnings by almost $2 billion.

But at the beginning (well, longer) Bezos fell into that narrative of “Big Tech” we all bought into: that brilliant, quirky, short-tempered, visionary, uncompromising entrepreneur that was popular in a moment when the tech industry claimed to represent a bold, democratizing idealism – well before our drugs wore off and the death of privacy and misinformation ballooned.

What may be most alarming about Amazon is how easily it seems to have converted government to its own purposes. At the local level, Amazon overpowers politicians and oversight committees. The company is beginning to dominate procurement for state and local governments – a $2 trillion slice of the economy that previously supported many local businesses, which have struggled (and largely failed) to keep Amazon off their turf. The company squeezes localities for all they’re worth. The tax breaks and demands for secrecy are breathtaking. These deals go through quickly, with elected officials often hiding negotiations from their own constituents during the process. If you have followed any of these Amazon “leaks” (read: info passed out by pissed off municipal employees) they are littered with code names for new Amazon projects, used by Amazon and officials alike: “Project Granite,” “Project Marble,” “Project Lux,” the unfortunately named “Project Big Daddy.” Politicians present these arrangements to citizens as done deals.

It is abundantly clear that Amazon is all too happy to prey on the weaknesses of an increasingly feudal society, and to exacerbate them. Deindustrialized towns are easy pickings, local businesses don’t stand a chance, labor law is all but useless in twenty-first–century America, and there are hardly any limits on legalized bribery. In many ways, Amazon is the perfect mechanism for exploring modern America, if only because its tentacles may be the last things connecting us all.

Amazon has put a drill into the cracks of American society and won’t stop until it’s extracted everything it can. The history of Amazon is not of a company, but of the country it has helped to reshape.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Tomorrow …

PART II

The new/not new Facebook leak

Last week it emerged that in 2019 you could abuse Facebook’s contacts lookup (find people on FB that you already know) to scrape semi-public information – email addresses and phone numbers, mostly. Someone used this to scrape several hundred million records before Facebook blocked this. Facebook said “Not an issue. We fixed it”.

Just one word : FANTASTIC!