[ Pour la version française, cliquez ici ]

[ Für die deutsche Version klicken Sie hier ]

Para la versión en español, haga clic aquí ]

Random musings in our unrelenting horizonlessness world

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

– E.O. Wilson, The Social Conquest of Earth (2012)

Captain’s Log, Star Date 2020 : our Age of Rona, Leninist teens on TikTok, the real fabric of our society, creativity, how we get lost in technology, American (un)exceptionalism … and our “Zeitgeist”

(with an enormous gratitude of debt to my editor, Charles Christian, and my media team: researchers Catarina Conti and Chloe Demos; the graphic artist/video team of Salvatore Costa and Marco Vallini; and my CTO Eric De Grasse

I. Our Age of Rona

II. We are lost in the technology

III. The dispersion of creativity, Part One: the coronavirus lockdown has accelerated the Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces

IV. The dispersion of creativity, Part Two: digitization accelerates the Cambrian Explosion of platform capitalism

V. Facebook, Google and … the end of Big Tech?

VI. TikTok

VII. America is a bizarre show

VIII. My concluding thoughts : “This is our Zeitgeist”

21 December 2020 (Chania, Crete) – Every year, for the last five years, my last post for that year has been “52 things I learned in [year]” – an attempt to reduce a firehose of “content” (as writing and video and photography is now called) received over 52 weeks.

But this year I decided to publish a working draft of my second major monograph: a collection of sketches of various lengths (“screengrabs” as it were) of thoughts and ideas percolating in my mind in our Age of Rona. A bit of self-discovery. As to my research and methodology, please see my Postscript.

I. Our Age of Rona

The feeling that civilization might end was only discussed amongst a few. And it was probably way too extreme, even for a cynic like me. My American and European cohorts had a blind assumption of relative stability. Shit was feeling a bit crazy in the beginning, but that fear of not knowing what tomorrow could look like had really not been there, at least in my lifetime. And our daily routines had added elements. I bleached my incoming snail mail, I wore (still wear) surgical gloves at the grocery store, I am ever vigilant over my space between fellow humans (and walking through their spaces) worried about transmission via “droplet spread”. And in the beginning I bought 100 cans of tuna, 50 packages of Orville Redenbacher popcorn, and 50 rolls of toilet paper.

I watched my neighbors become remote workers, and homeschoolers – all at once. Mass school closures meant that many new remote workers face the competing challenges of full-time work and full-time childcare. It has led to scores of “Remote Control” workshops where parents got expert advice on managing multiple tasks and warding off chaos.

In Brussels, I served on neighborhood care teams distributing food and comfort to those who were no position to venture out.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a challenge perfectly crafted to feed on our every societal and informational weakness. From the American perspective it was worse: health insurance, inequality, federalism, leadership, Trump, individualism, social media, broadcast media – all the shortcomings of every one of those elements felt built to exacerbate this crisis.

And this enemy had no side. Whatever/whoever your enemy or your country’s enemy has been, there was always a very clear character that brought you grief. That’s how our reality show works. It’s maddening, but we’ve all learned to process everything like this. This coronavirus was clearly none of the above. There was no “us” versus “them”.

What was equally maddening was the “we are all in this together” mantra was bullshit. It was wrong. Not true. And that was due to an unequal global footing, different degrees of isolation and surveillance, as well as increased government control. The border was forever tightening around you, pushing you ever closer to your body. The new frontier was the mask. The air that you breathe has to be yours … alone.

The pain of social distancing and isolation isn’t negligible, but neither is it lethal, and “sheltering in place” counts as a privilege, even a luxury. For those working on the frontlines in hospitals, or delivering food, or performing any of the essential jobs that the ruling elites hardly noticed before, every day is an endless confrontation with the risk of contagion.

And we were (still are) troubled, depressed, confused. We want constant updates. We need a constant flow of new information. It’s how everything has wired us over the past few decades. We’re exploring the charts and reading the posts. We can find something new every minute of every one of these days, yet, none of it really makes a difference. But, we’re sitting at home and need those dopamine fixes, even more, to get us through the day. We are not patient. We need an answer and an update … NOW!

I worked my way through all the twisted paradoxes. Because it was a time of paradoxes and contradictions. The coronavirus leaps out of some animal into some reservoir host, across into humans, through world markets, and gets spread by our most dynamic bits of modernity. That’s a paradox. It’s tiny, 120 nanometers. It brings down the world economy, which is one of the biggest things that we know. That’s a paradox. And then, there’s this paradox: we need “to act collectively”, but we also need “to take individual personal responsibility”. So it really is very much a strange time of paradoxes that we’re trying to navigate.

And that required navigating impenetrable graphs and dubious advice. Because this coronavirus, with its health, social, scientific and economic impacts, has made the content production engine of this world go into overdrive, leaving most of us struggling within an infodemic. Unreliable information also adding anxiety as it ultimately leads to contradictions, doubts, and lack of trust.

But I was prepared. And I had immeasurable help on the science from people like Randy B. and S. Churchill and the teams at the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Center to work me through the science. Because we are in an age of atomized and labyrinthine knowledge. Many of us are forced to lay claim only to competence in partial, local, limited domains. We get stuck in multiple affiliations, plural identities, modest reason, fractal logic, and complex networks.

But many of us do not get stuck, and right now none of can afford to get stuck. Yes, as difficult as it is, we must be interdisciplinary. We must focus. We must take all those pieces, shards, ostraca, palimpsests, barrage of news clips and web sites screaming by us and determine what we think is key to know and internalize it.

This coronavirus has forced us (once again) to see that there really is no division between the “hard” sciences” and the “soft” sciences. Our move to take traditional disciplines and fragment them into 1,000 autonomous domains is misguided. To understand, to cope with this coronavirus and what will become the “new normal” (a dubious term but it will need to suffice for this post) we need to deal with the complexity of this new territory. We are forced to become interdisciplinary. The French philosopher, Marcel Gauchet wrote:

Specialization, fragmentation of knowledge will resoundingly lead to superficial generalization by the media, and everyone will be fixed in fragmented competencies. It will lead to the entrenchment of the elites and it will lead to universal ignorance and most probably universal corruption, that will lead to a populism with all of its aberrations.

For most of time, Earth was a safe and stable home for our world.

Well, ok. Not quite. As Dr. Chris Donegan corrected me (a chap who tags himself on Linkedin as a “Skeptical Empiricist”, who keeps my posts honest, and who has a day job as a seasoned investor and advisor focused on IP-rich private companies) :

Not so fast. In fact, safety and stability are posted WW2 illusions created by Western style public health measures, vaccination and penicillin. The norm of life is “nasty brutish and short” to paraphrase Hobbes. As for complexity: one thing that everyone learns when they go down the PhD rabbit hole of science specialism is that the more they learn the greater their awareness becomes of their own ignorance. The current fantasy of AI as a panacea to big data rich problems is a continuation of the delusion. The governments of most developed nations formed their models in the 18th or 19th centuries. Very few are fit for purpose in the 21st. But bureaucracies don’t simplify themselves.

But over the last century, our world has been advancing exponentially in technology but remaining stagnant in wisdom. We are rapidly gaining tremendous powers but still behaving like short-sighted primates. The voice of wisdom is there, but it’s being trampled over by political parties, religions, and nations too mired in blind conflict to lift their heads up and see the bigger picture. Our world is so, so stubborn about growing up.

I am still struggling with this stuff. I have much to learn. So far all the complex/interlocking dynamics exposed show a basic absurdity at the heart of our global society. It is not a system aimed at satisfying our desires and needs, at providing humans with greater amounts of physical utility. It is instead governed by impersonal pressures to turn goods into value, to constantly make, sell, buy, and consume commodities in an endless spiral and ignoring the effect of that system on the “normal human”.

Because containing the spread of the coronavirus is about more than practicing good hygiene. On trial is a whole global system of profiteering and its structural laws and incentives. What the pandemic has revealed is not just that companies are out to get rich – a story as old as time – but specifically our unprecedented degree of global interdependence in the year 2020.

The coronavirus seeks only to replicate. We seek to halt that replication. But as Martin Wolf, columnist for the Financial Times, noted:

Unlike the virus, humans make choices. This pandemic will pass into history. But the way in which it passes will shape the world it leaves behind. It is the first such pandemic for a century. And it comes to a world that – unlike in 1918, when the Spanish flu hit – has been at peace and enjoys unprecedented wealth. We should be able to manage it well. If we do not do so, this will be a turning point for the worse. Making the right decisions requires that we understand the options and their moral implications.

I am a realist and I am a cynic. To me that means we’ll need to decide who will bear the costs of those choices – and how.

And of course COVID is just part of a much bigger issue. New evidence keeps mounting that the Anthropocene has truly arrived:

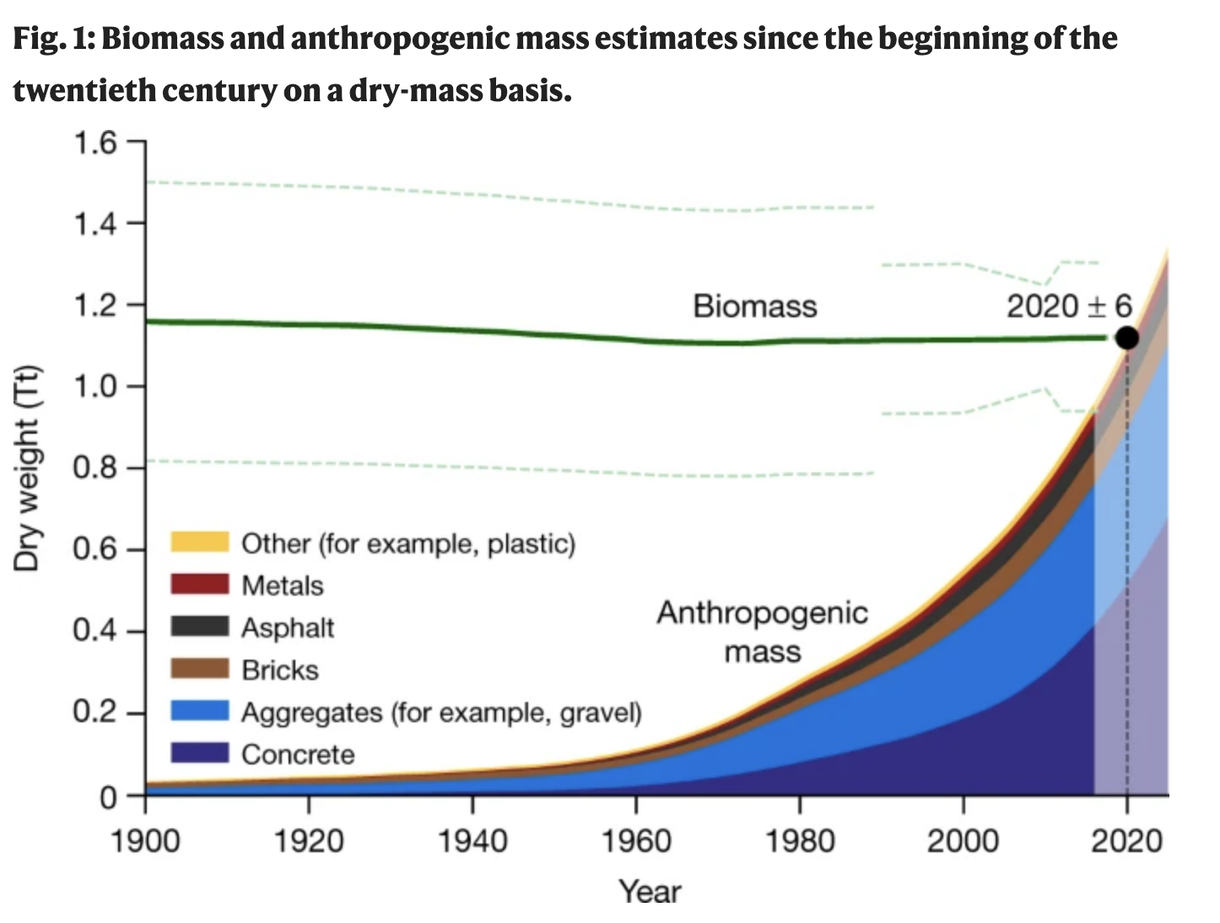

The combined mass of human-made objects now exceeds the mass of natural objects on Earth, according to Emily Elhacham and colleagues. The mass of plastic, at 8Gt, is double that of animals.

We live in an inherently unstable system: everyone is connected but no one is in control. The world is always in overdrive, with a relentless acceleration in human development over the past two centuries. We are living longer, producing more, consuming more, devouring energy and space on an unprecedented scale – and generating waste and emissions in tandem. This pandemic was “nature’s revenge” on our voracious species.

Will we prevail? Nah. Much of the glue holding modern societies together is alarmingly fragile, and triggers like September 11th and this pandemic can shatter the facade “we are all in this together”. With devastating consequences that we are only just beginning to understand. I opened this piece with a quote from the evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson from one of my favorite books which he published in 2012, The Social Conquest of Earth:

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

As he details in his book, although kin psychology lies at the foundation of genetic ingroups, humans form factions around anything and simply being a member of a group is usually enough. This is called the “minimal group paradigm” and it is one of the most well-established findings in social psychology – research has shown that even beliefs about whether hotdogs are sandwiches can generate discrimination. Our instinct to assemble and join insular, protective groups is so ancient and powerful that it is unlikely we will ever arrest it, and despite the more sinister ramifications that result from forming coalitions, we probably wouldn’t want to even if we could.

Also, in my COVID series, I often quote Gaia Vince (a long-time Twitter connection of mine), usually her book “Transcendence: How Humans Evolved Through Fire, Language, Beauty, and Time” and she notes:

Humans do not operate within their ecosystems in the same way as other species, even other top-level predators. We don’t have an ecological niche, but rather we dominate and alter the local—and now, global—ecosystem cumulatively to suit our lifestyles and improve our survival, including though habitat loss, introduction of invasive species, climate change, industrial-scale hunting, burning, planting, infrastructure replacement, and countless other modifications. It means that while other species do not naturally cause extinctions (except in rare circumstances, such as on islands), humans currently threaten 1 million of the world’s 8 million species.

We are a part of the biosphere and as we blunder into ecosystems we must be mindful of the greater systems that we are all a part of. A tweak to one part of the network can have far reaching consequences (good or bad) for us all. Our species has, in an instant of planetary time, become a potent planet-scale destroyer.

All of this reminded me of my comfort living and writing from a remote part of Greece, a bit mysterious at times and even a bit impenetrable at times, but awesome – made of earth, air, fire and water. It breathes. Here you can get a bit nearer to the stars and the ether.

It also reminded me of those of us living in urban areas and how the city is a lie that we tell ourselves. The crux of this lie, as noted by Sam Grinsell (a friend, who is a historian of the built environment at the University of Antwerp in Belgium who knows Wuhan, China which became the epicentre of COVID-19) has noted we separate human life from the environment, using concrete, glass, steel, maps, planning and infrastructure to forge a space apart. Disease, dirt, wild animals, wilderness, farmland and countryside are all imagined to be essentially outside, forbidden and excluded. This idea is maintained through the hiding of infrastructure, the zoning of space, the burying of rivers, the visualisation of new urban possibilities, even the stories we tell about cities. Whenever the outside pierces the city, the lie is exposed. When we see the environment reassert itself, the scales fall from our eyes.

It’s also why I marvel when art or artefacts or footprints from our Palaeolithic period are suddenly exposed, hidden for 850,000 years, always found in some remote part of the world.

That sense of remoteness, of distance from and hiddenness, are merely a side effect of humanity’s planetary domination: the only places where traces of the deep past remain are places we haven’t built over or crushed underfoot. There could be Neanderthal remains all around where I’m writing this (Paris), but those traces, if they ever existed, are long and permanently lost. We find evidence mainly in caves and because they’re the only places where remains haven’t been washed away by time and tide and shifting glaciers. This is the same reason the far past continues to make news: we are constructing knowledge from scraps and fragments, and big new discoveries have the potential to rewrite the human story.

II. We are lost in the technology

When we talk about technology, we get trapped in a spiral. We lapse into magical thinking, unable to navigate a web of complexity, blind to simple solutions, staring down broken systems. And to understand you need to start with some very basic stuff: the architectural principle of using multiples of perspectives and multiples of dimensions which is the only means to investigate and collate data.

And it means looking at all types of sources such as Aaron Frank’s 3D map data study which shows the technology infrastructure for the 21st Century (click here).

I am thankful for the help I have had these last few years to compare tech notes with Thomas Behrens, Allen Woods, David Knickerbocker, Nick White, Peter Stannack, Dr. Chris Donegan, Ned Farhat and Armin Roth as I went down the rabbit hole. All have taught me anything really new is still too close to the engineers to be simple or reliable.

Each generation sees the technological advances of the previous era – no matter how near – as antiques of an ancient world. People like to think the world has truly changed only in their own time. But the feeling of witnessing a spectacular acceleration that rejects outright all past centuries, relegating them to an undifferentiated backwater incommensurable with current experience, is not solely the privilege of children who grew up with the internet and see the gigantic computers conceived after World War II as antiques no less foreign to contemporary life than the powdered wigs of the eighteenth century or the quadrigae of the Circus Maximus.

Our institutions of governance and law and commerce mostly originated during the 18th century Enlightenment. As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, linear thinking and logic (Cartesian and otherwise) are no longer suitable for this connected and complex world. Yes, we have gone through many evolutions and revolutions, each different. We have been able to discern some patterns from the past – but they will not serve us today. Our shift to an electric-digital-networked age is unique. Distributed information and communication technologies have converged, creating a societal infrastructure like no other we have experienced. We are unprepared.

“Tech” has all of this complexity, but we’re having to work this out a lot more quickly. It took 75 years for seatbelts to become compulsory, but tech has gone from interesting to crucial only in the last five to ten years. That speed means we have to form opinions about things we didn’t grow up with and don’t always understand quite so well as, say, automobiles and supermarkets.

Before I retired, I had the good fortune to work in what once were three discreet technology areas: cyber security, digital and mobile media, and legal technology. I spent a total of almost 40 years across those worlds, although I came late to legaltech – spending only about 12 of those 40 years on the legaltech floorboards. In years gone by these were discreet areas.

They are no longer discreet but continue to overlap, though most of the practitioners in each discipline seem stuck in their respective silos, rarely venturing out to learn/understand the other two. Those that do make it out of their silo only make superficial contact with their “neighbors”.

But as I have noted in many previous posts, the modern human (and especially the modern technologist) moves through all three of those myriad, overlapping spheres. They are forever entangled. It is because we live in a world of exponential companies, fundamentally different in characteristics to industrial age ones.

To borrow from hydraulics, it’s the compression ripple writ large. Traditional sector classifications (developed to categorize the industrial economy) make no sense. What is included in the bucket of “information technology sector” are companies serving the modern economy across food, power, transport, health, security, logistics, etc., etc. by harnessing modern capabilities (i.e. “information technology”). The thing that the “IT” sector has in its hands are exponential, rather than extractive, technologies. And while old-economy companies are trying to integrate technology into their business, for new-age companies technology is their business.

It’s why the big deals, the big events of 2020 … the NVIDIA/ARM deal, the TikTok imbroglio, the Apple “Time Flies” event, etc. … are all overlapping, all entangled.

All of our systems have become more sophisticated and more ubiquitous – general data collection, embedded mobile device sensors, cameras, facial-recognition technology, etc. We are experiencing what data analysts call “phase transition” from collection-and-storage monitoring to “mass automated real-time monitoring”. Much more importantly, though, they are bringing about this change in scale, so these tools also challenge how we understand the world and the people in it.

Plus, this degree of surveillance … and it is surveillance … will continue to emerge, and not simply because the technology is improving. As Jake Goldenfein (a law and technology scholar at Cornell University who covers emerging structures of governance in computational society) notes in his forthcoming book:

“Instead, the technologies that track and evaluate people gain legitimacy because of the influence of the political and commercial entities interested in making them work. Those actors have the power to make society believe in the value of the technology and the understandings of the world it generates, while at the same time building and selling the systems and apparatuses for that tracking, measurement, and computational analysis.”

But the big knife we have wielded, to kill our own data privacy? Convenience. We think we want our data to be private, or that we can choose our degree of privacy. Shoshana Zuboff and Jamie Bartlett both use the phrase “a reasonable quid pro quo” : we make a calculation that we will trade a bit of personal information for some valued services. Simply put … we scream “PRIVACY! yet vent our spleen and all our personal data across the social media Milky Way, and use every technological devise we can to ease our convenience.

Danny Hillis provides some perspective. In a long-form essay on Medium titled “The Enlightenment is Dead, Long Live the Entanglement”, he notes that in the Age of Enlightenment we learned that nature followed laws. By understanding these laws, we could predict and manipulate. We invented science. We learned to break the code of nature and thus empowered, we began to shape the world in the pursuit of our own happiness. With our newfound knowledge of natural laws we orchestrated fantastic chains of causes and effect in our political, legal, and economic systems as well as in our mechanisms. He says:

Unlike the Enlightenment, where progress was analytic and came from taking things apart, progress in the Age of Entanglement is synthetic and comes from putting things together. Instead of classifying organisms, we construct them. Instead of discovering new worlds, we create them. And our process of creation is very different. Think of the canonical image of collaboration during the Enlightenment: fifty-five white men in powdered wigs sitting in a Philadelphia room, writing the rules of the American Constitution. Contrast that with an image of the global collaboration that constructed the Wikipedia, an interconnected document that is too large and too rapidly changing for any single contributor to even read.

We are so entangled with our technologies, we are also becoming more entangled with each other. The power (economic, physical, political, and social) has shifted from comprehensible hierarchies to less-intelligible, incomprehensible networks. And we cannot fathom their extent. And virtually nothing is private.

It is a power shift, really. A power shift from the ownership of the means of production, which defined the politics of the 20th century, to the ownership of the production of meaning.

For me, I have never been satisfied with just having vague notions of how all these converged distributed information and communication technologies worked. I needed to do a deep dive, to understand. You may not need to comprehend the precise details of how modern algorithms and these intermediated, platform-based environments work, but you need to know how to assess the “big picture”. You need to arm yourselves with a better, deeper, and more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon.

It is not easy, but it can be done. Just look at AI. It took time to develop a framework for deconstructing algorithmic systems but we did it, creating three fundamental components: (1) the underlying data on which they are trained, (2) the logic of algorithms themselves, and (3) the ways in which users interact with the algorithms. Each of these components feeds into the others. We learned the intended and unintended consequences of algorithmic systems.

And just a general observation about machine learning (ML). Last month Google’s DeepMind announced “Alphafold”, which uses ML to work out the likely structures of complex folded proteins. I covered this … as well as Deep Mind’s incredible history … in depth two weeks ago so I shall not repeat myself.

But we are also seeking huge numbers of boring old-economy companies automating internal processes with pieces of ML that have very quickly become generic commodities. Businesses are shifting their AI priorities not just to strategic applications but “grunt work” tasks … digitizing documents, automating invoices, monitoring inventory, making beer, etc.

We seem to have two tracks in ML. Somehow ML is both rocket science and tractors.

Plus we are getting some real brainpower to analyze all of this, such as the brainiacs which designed an AI database to make past AI failures visible (click here).

I am fascinated with the shift from technology writing in the late 1980s to today. In the 1980s, when I was working on Wall Street, I had to follow all this stuff and the content was product centric: “how-tos”, opinion pieces about the speed of processors or the quirks of software. The “Big Picture” story was about the cost or complexity of managing an enterprise system or network.

Today, the focus of technology writing is more varied. And it is daubed or immersed in socio-politico broth. What’s happened between the late 1980s and the quite remarkable 2020s is that technology has become more than how to connect a printer to a personal computer or ways to reduce the cost of adding a new user to the corporate network. More than half a century after the digital shift began, individuals are looking at the world and finding it is a datasphere.

It . is . astounding :

• The multi-touch smartphone, launched 10 years ago with Apple’s first iPhone, has conquered the world, and it’s not done getting better. It has, in fact, become the new personal computer. But it’s a maturing product that I doubt has huge improvements ahead of it. Tablets rose like a rocket, but have struggled to find an essential place in many people’s’ lives. Desktops and laptops have become table stakes, part of the furniture.

• Ambient computing, the transformation of the environment all around us with intelligence and capabilities that don’t seem to be there at all, is moving so fast we’ve turned over our homes, our cars, our health, and more to private tech companies, on a scale never imagined.

• We are increasingly relying on machines that derive conclusions from models that they themselves have created, models that are often beyond human comprehension, models that “think” about the world differently than we do. We are building models beyond understanding.

In his series on machine learning, Adam Geitgey explained there are generic algorithms that can tell you something interesting about a set of data without you having to write any custom code specific to the problem. Instead of writing code, you feed data to the generic algorithm and it builds its own logic based on the data. It’s how machine learning was furthered by creating an artificial neural network that models in software how the human brain processes signals. Nodes in an irregular mesh turn on or off depending on the data coming to them from the nodes connected to them; those connections have different weights, so some are more likely to flip their neighbors than others. Although artificial neural networks date back to the 1950s, they are truly coming into their own only now because of advances in computing power, storage, and mathematics. The results from this increasingly sophisticated branch of computer science can be deep learning that produces outcomes based on so many different variables under so many different conditions being transformed by so many layers of neural networks that humans simply cannot comprehend the model the computer has built for itself.

Yet it works, albeit in fits and starts – one step forward, three steps back. It’s how Google’s AlphaGo program came to defeat the highest ranked Go player in the world, and Alphafold worked out the likely structures of complex folded proteins.

NOTE: AlphaGo was trained on thirty million board positions that occurred in 160,000 real-life games, noting the moves taken by actual players, along with an understanding of what constitutes a legal move and some other basics of play. Using deep learning techniques that refine the patterns recognized by the layer of the neural network above it, the system trained itself on which moves were most likely to succeed. Next year I’ll write a post on how Alphafold worked out the likely structures of complex folded proteins.

Clearly our computers have surpassed us in their power to discriminate, find patterns, and draw conclusions. That’s one reason we use them. Rather than reducing phenomena to fit a relatively simple model, we can now let our computers make models as big as they need to. But this also seems to mean that what we know depends upon the output of machines the functioning of which we cannot follow, explain, or understand.

Plus one thing, from the Dark Side, which I dropped from this draft and will save for next year because it needs a more complete discussion: how venture capitalists have deformed capitalism. They are part of this “second economy” that has become organized around a group of new companies whose business, like the trading monopolies of the eighteenth century, is the transformation of the capitalist system itself. And once again, their commercial ventures are so far-reaching that they promise to subsume the political system. They saw the internet as a “new-found-land” whose inchoate expanse has been coded into property using legal concepts directly descended from those with which America was founded. They possess political power greater than most heads of state. And the old caveats apply once more. This “second economy” serves elites almost exclusively, and yet again, it is chiefly financialized.

Nothing new here, really. I’ll write about George Luk’s book The Menace of the Hour, which was published in 1890 but set in 1988. He offers a prophetic glimpse into America’s terrifying future, depicting a country where democracy has been corrupted into an oligarchy controlled by the great “Rings” of industrial monopolies. The book’s cover:

Yes. There is lots and lots out there. You owe it to yourself to look, to see the “Big Picture”.

III. Dispersion of creativity, Part One: the coronavirus lockdown has accelerated the Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces

One of the biggest, ongoing changes in media … accelerated by the coronavirus lockdown … has been the Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces. Over the last 5-8 years we have been learning so much about the dynamics of digital places and semi-spatial software, and the mega-leap in video and film production. This will drive incredible evolution in design and content patterns over the coming months and years.

There has been a tectonic shift to “new new” social media. When I joined Twitter and Linkedin 15 years ago (the first one I have used for the firehose of news, the second for more thoughtful chats) I wanted, more than anything, to communicate directly with key sources I depended on for my writing and, in fact, all my media work. I needed feedback on the pieces I wrote. I had a chat with Charles Arthur, the freelance journalist and former technology editor at The Guardian newspaper (author of the monumental Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet; I highly recommend it – puts a lot of today’s tech battles in perspective) and he noted:

Screenwriters get to go to meetings and hang out on set, playwrights can watch an audience respond to their words up close and in real time – but writing is a lonely business that can involve spending many days, weeks and months in isolation crafting something that will be consumed privately and elsewhere by strangers.

I am by profession a lawyer, a writer, a journalist, a media producer – and in my wildest dreams, a historian. As a lawyer I began my career working for clients in the technology, media, and telecom (TMT) sectors. I stayed in those sectors. It drew me to my own video and film production work, and although retired so I could write more, I still produce a bi-monthly newsletter for my TMT clients while my media team continues to produce bespoke videos for those clients.

When I first began creating videos and films, my storyboards … the graphic organizers that consist of illustrations or images which are displayed in sequence for the purpose of pre-visualising a motion picture, animation, motion graphic or interactive media sequence … were my narrative building blocks, and I used those same techniques in writing.

Since being on both Twitter and Linkedin I’ve had conversations with scores of people (many strangers) who have suggested research avenues I had not considered. I have had a ringside seat to watch investigative journalists at their best. All that plus streams of marvellous posts on art and culture, and wonderful science. Ok, I must fully admit I also enjoyed the videos of stupid drunk men failing to leapfrog barbecue grills.

This social media shift can be attributed to two things in particular. The first is the development of wonderful curation tools. Like many of my media cohorts, I don’t “read” Twitter or Linkedin or any mainstream social media anymore. I use APIs like Cronycle and Factiva that curate the whole social media firehose so I only receive selected, summarized material that pertains to my research or reading need.

The second is even more important. The idea of my company, Luminative Media, came from conversations with my media cohorts who are developing the “new new” social media: the growth of independent creatives building franchises around their talents, where I (and a growing tribe) now spend our social media time, away from the main firehose of social media. Most are paid newsletters. Platforms such as Patreon and Substack (or Kanopy for short movies) have created a tremendous opportunity to go direct to audiences with content relevant to their specific interests, unmediated by large organizations and social media platforms and their horrible cost structures.

But really, if you look back at the development of digital media since the turn of the millennium, artists have been writing, and circulating their writing, like never before: essays, criticism, manifestos, fiction, diaries, scripts, and blog posts have charted a complex era in the world at large, away from mainstream social media, weighing in on the exigencies of our times in unexpected and inventive ways.

This is all part of the “Passion Economy”, people monetizing what they love. The global adoption of social platforms like Facebook and YouTube, the mainstreaming of the influencer model, and the rise of new creator tools has shifted the threshold.

I follow the business model of Benedict Evans, Kevin Kelly, and Ben Thompson (I only mentioned those three; many use this model) which is the “True Fans” vision where a blogger creates a base of 100 (or even 1,000) subscribers paying $100 a year for her/his musings.

Kevin and Ben and Benedict and folks like Charles Arthur and Helen Lewis are in the stratosphere with 10,000 to 25,000 paid subscribers. But they also have a category for free subscriptions, which is “blog lite”.

I am a weeee bit lower on the ladder with just over 1,200 paid subscribers, mostly in the TMT and cyber industries. The bulk of my subscribers … 25,000+/- … get “blog lite”.

The economics work something like this: a creator can cultivate a large, free audience on horizontal social platforms or through an email list. He or she can then convert some of those users to patrons and subscribers. The creator can then leverage some of those buyers to higher-value purchases, such as extra content, exclusive access, or direct interaction with the creator.

This strategy is closely related to the concept of “whales” in gaming, in which 1 to 2 percent of users drive 80 percent of gaming companies’ revenue (though that model is evolving). Put simply, if you can convince a small number of super-engaged people to pay more, you can also have a general audience that pays less, or nothing, but you still get network effects (I average about 15 new subscribers every month, 1-2 being paid subscribers). By segmenting the customer base and offering greater value to top fans – at a higher price point – creators can earn a living with a smaller total audience.

That’s the wonder of this Cambrian Explosion: the internet enables niche in a massively powerful way. And if you think long and hard about it is this not just an example of convergent evolution? Social media has collapsed high and low culture into a sinuous, middling unibrow. It made room for the fringe to graze the mainstream while allowing outliers and niche practitioners a foot in the door. Yes, institutional barriers to entry persist, and the cost issue will remain difficult (not all “tribes” have the same level of funding), as will the technology/expectation gap.

But a new art world has never been more possible although given it’s structural, this revolution won’t be televised until it’s irreversible and given us its first, fixed forms. The bet is safe, though: anticipate swerves, not lineal progression, wherever generalized crisis meets new media, patronage and deep shifts in values. The history of the avant-garde has never been more forward-facing.

As I have noted, the pandemic’s most enduring feature will be as an accelerant of existing trends. The trend that encapsulates the greatest reshuffling of stakeholder value in recent history is what tech analysts Scott Galloway and Ben Thompson have called “the Great Dispersion”. It’s similar to prior macro trends like globalization and digitization.

This dispersion of creativity is seen in Etsy – a pandemic winner whose prosperity is nothing short of inspiring – that enables artisans to reach a global audience. YouTube made video stars out of millions, and now TikTok is leapfrogging YouTube in the mobile space (I’ll address TikTok below). As I noted here, Substack, Patreon, and OnlyFans are likewise disarticulating creators from traditional gatekeepers. It appears algorithms have a better eye for great content than Meg Whitman.

It’s the shifting shape of the writing-publishing life. Successful writers must now juggle the demands of the creative life with the need to be business-like about their social media profiles, sending out newsletters or dropping samples of their work on these new publishing platforms.

That inequality we are seeing in our daily physical lives is moving online – priority data, less ads, and the “Substackification of everything” will lead to radically different experiences and more relevant knowledge for those who pay and those who do not.

And it has already lead to private channels by and between people who explicitly chose to receive it. This is the online environment where many feel most secure. Where they can be their “real self.” These are all spaces where depressurized conversation is possible because of their non-indexed, non-optimized, and non-gamified environments.

But it is also happening in the even bigger platforms – commerce. So let’s discuss that.

IV. The dispersion of creativity, Part Two: digitization accelerates the Cambrian Explosion of platform capitalism

For the last four years I have written a series of posts about the accretive paradigm shifts in our economy and social lives, mostly digitization, and complex/interlocking dynamics at the heart of our global society. But not much on the big 2020 trend: “dispersion”. This month Scott Galloway wrote:

The market added half a trillion in value in two weeks in December: AT&T busted a baller move to a rundle, the FTC filed suit against Facebook, and an overhyped DoorDash and underhyped Airbnb went public.

Plus, AT&T’s announcement that it will release movies simultaneously on HBO Max and in theaters predictably pissed off Hollywood players, who make millions off the current system. But Christopher Nolan calling HBO Max “the worst streaming service” is similar to JCPenney calling Amazon circa 1999 a terrible experience. So many people … just … do … not … get … it.

It is so simple, really. I am indebted again to Dr. Chris Donegan and Peter Stannack for being able to brainstorm the the underlying economics:

• The market favors recurring revenues and narrative over transactional revenues and EBITDA. Last week, AT&T went gonzo on theaters, opting for the consumer. AT&T is poised to recognize an increase of $100 billion or more in market cap in 2021 on its transition from a conglomerate that makes no sense … to the world’s largest recurring-revenue firm.

• And those monster IPOs last week, hitting $billions of market cap in one day? DoorDash, a food delivery firm with multiple well-capitalized competitors, is now worth $60 billion. Its market cap is almost equivalent to Moderna, the biotech company that created a Covid-19 vaccine in less than a year. Said tech analyst Casey Newton:

One is a warrior that may defeat a pandemic, and the other delivers my burrito bowl. One is overvalued.

• Airbnb, however, is not. The firm’s offering price was $68, but closed at $144 per share with a market cap of over $100 billion, as many predicted.

FULL DISCLOSURE: I have a small position in Airbnb via a private equity master fund that participated in a larger private equity funding for Airbnb early on. Through that investment I was able to learn about technical integration, platformization, the economic dynamics of those platforms, enabling them to shift the economic dynamics of competition and monopolization in their favor. And how new power relations are formed.

• Airbnb has dispersed the vacation travel supply chain. It has a dominant brand, a global supply network, and a talented leadership team. AirBnB refigured its software development model, in which their stack was divided into a number of distributed services rather than one singular application. At the end of this infrastructural decomposition, AirBnB recomposed itself into a multitude of interconnected services, a process that has come to define platforms.

Every platform starts with a single monolithic application. For early Airbnb, this included functionality like search, payment systems, and fraud prevention, all in the same code base. There are actually many benefits to a monolith: because they’re simpler, they’re easier to build, develop, monitor, deploy, you name it.

But monoliths don’t scale. And Airbnb needed distributed value-added services of de- and recomposed platforms. Ultimately, this has led to a much deeper technical integration of these ecosystems.

Platforms are horizontal networks that connect buyers and sellers, speakers and listeners, creators and consumers, to one another, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. The internet is such a platform, of course, and it hosts many others: Twitter and Facebook, YouTube, Etsy, eBay, and Airbnb. These platforms have become the connective tissue for billions of people. They are sub-economies that have become nation-states with market capitalizations greater than the GDP of Honduras.

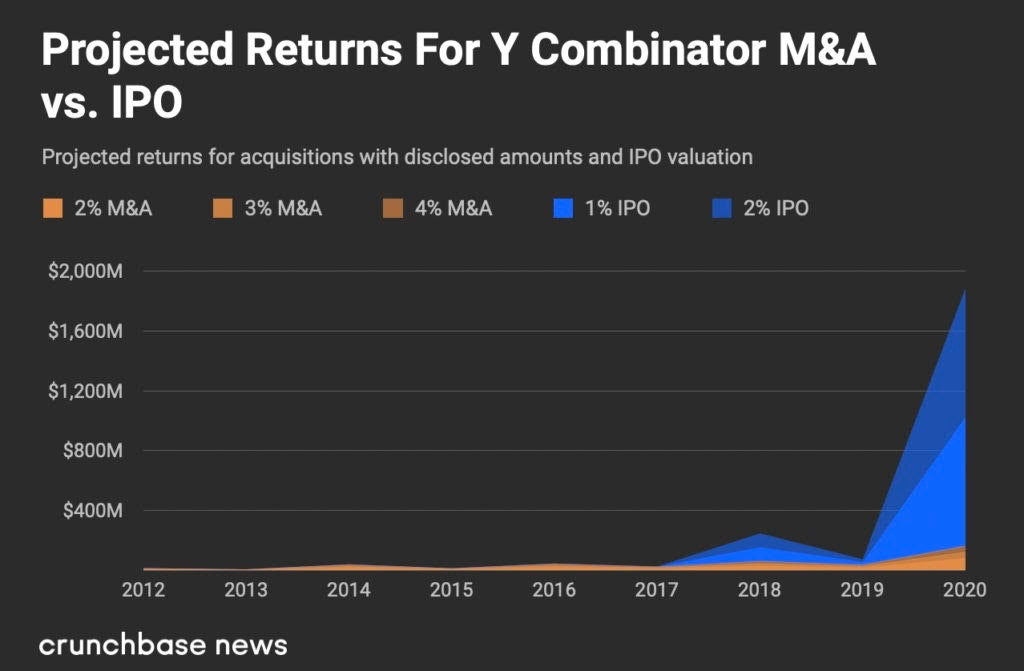

And an important point. Airbnb was one of the big winners from the Y Combinator accelerator program, alongside Doordash.

Airbnb joined YC in January 2009, showing how tough the accelerator business is – and how much patience is required. There is a good discussion of how this also works at CrunchBase (click here).

And building a platform can generate huge returns. In 2000, Amazon launched its own platform, permitting third parties to sell goods alongside Amazon’s own offerings. In 2017, unit sales on Amazon Marketplace exceeded Amazon’s direct offerings and have only increased their share since. In effect, Amazon became a minority player on its own platform, a result that might strike a less innovative CEO as a bad outcome.

But Bezos knows platforms, and so does the market. Amazon’s stock has appreciated at 3x the pace of Walmart’s since 2017, as Amazon uses its platform dominance to create scale that is … Amazonian.

Ah. But will the DOJ put an end to all these dreams? Let’s move on.

V. The Google, Facebook … and the end of Big Tech?

This month we saw the FTC and 48 states file an antitrust lawsuit against Facebook. This formed the second of two dots, the first being the DOJ’s case against Google announced over the summer. So, two dots make a line, and that line points towards the end of Big Tech as we know it. Or so say the pundits. But it’s a wee bit more complicated than that.

All industries are subject to general legislation – to criminal law, securities law, workplace safety law and so on. But some industries are important enough and complicated enough to get their own specific laws, and their own regulatory agency to manage and enforce that – hence food, aircraft, banks or oil refining are “regulated industries”.

It’s very clear that technology companies are moving much deeper into this regulated sphere – technology is becoming a regulated industry. But this also means lawyers and civil servants taking decisions (or at the very least, deciding not to take decisions) in very complex ongoing arguments around everything from content moderation to app store competition to encrypted messaging.

These are all interesting problems in their own right, but from a regulator’s perspective, one of the problems to address is just how many problems there are. “Tech” is a very diverse, widely-spread industry that touches on all sorts of different issues, and indeed lots of other industries, some of which are also regulated. These issues generally need detailed analysis to understand, but these issues tend to change in months, not decades.

I’ll have more to say on this in the coming year so for now a few general points.

The DOJ case in a nutshell: Google may have earned its position honestly, but it is maintaining it illegally, in large part by paying off distributors. That stands antitrust enforcement on its head. We’ll see if this DOJ change of tack goes anywhere.

Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple dominate because consumers like them. Each of them leveraged technology to solve unique user needs, acquired users, then leveraged those users to attract suppliers onto their platforms by choice, which attracted more users, creating a virtuous cycle which Ben Thompson has written about as “Aggregation Theory”.

Aggregation Theory is the reason why all of these companies have escaped antitrust scrutiny to date in the U.S.: here antitrust law rests on the consumer welfare standard, and the entire reason why these companies succeed is because they deliver consumer benefit.

So the DOJ, taking a very narrow focus, does this: instead of trying to argue that Google should not make search results better, the Justice Department is arguing that Google, given its inherent advantages as a monopoly, should have to win on the merits of its product, not the inevitably larger size of its revenue share agreements.

In other words, Google can enjoy the natural fruits of being an Aggregator, it just can’t use artificial means – in this case contracts – to extend that inherent advantage.

And how complicated is this stuff? Google’s payments to Apple to promote its search engine in iPhones, iPads and Mac computers are at the center of the Department of Justice’s antitrust lawsuit against the tech giant. The suit alleges this creates a “continuous and self-reinforcing cycle of monopolization” by limiting which search engines consumers can use.

But as someone who studies platform markets, competition and industry structure, I believe the agreement seems more like a damning indictment of Apple’s own potentially illegal business practices. The Department of Justice alleges that Google pays Apple and other device-makers to set its search engine as the default “on billions of mobile devices and computers worldwide,” thus controlling how users access the internet. Apple’s role as the gateway to billions of searches is the critical factor here. Why are they not subject to suit? Is this a search market case or a smartphone OS market case? And what happens next year? If Apple makes a search engine and uses the market dominance of iOS to create competition in search, what market definition is that?

Platforms provide the technological and economic infrastructure and set the rules participants must abide by. This gives them significant power as the access point to potentially massive numbers of users, which has been the core issue underlying past antitrust actions against major tech companies such as Microsoft in the late 1990s. It seems like the part about the Google-Apple partnership should be more directed toward the company that actually controls the access to consumers.

And the Facebook suit? In brief, the government and the states want to force Facebook to spin off Instagram and WhatsApp, two major parts of its social media empire. The cases are compelling in enumerating examples of predatory behavior, and there is no question Facebook has acted improperly in numerous instances.

NOTE: for an in-depth piece on Facebook’s efforts to make WhatsApp profitable, click here. It’s hard to understate just how powerful WhatsApp is across the Global South. For many, WhatsApp is the internet. The question is whether U.S. lawmakers grasp this.

It’s also why Facebook is building its own operating system. It doesn’t want its hardware like Oculus and Portal to be at the mercy of Google because they rely on its Android operating system. By moving to its own OS, Facebook could have more freedom to bake social interaction deeper into its devices. One added bonus of moving to a Facebook-owned operating system? It could make it tougher to force Facebook to spin out some of its acquisitions, especially if Facebook goes with Instagram branding for its future augmented reality glasses.

That may be OK. But as I look across the vast list of all Facebook’s misdeeds, I am not convinced that for all the different kinds of damage this company causes society, its continued ownership of these two properties should be at the top of the list. I am also not convinced that its ownership of these services is the most important way Facebook harms consumers, protecting whom is ostensibly the purpose of American antitrust law. Nor am I convinced that consumers – or call them here “voters” – want their government officials breaking apart a company that more than half of all Americans use every day.

As Ben Thompson notes, the FTC complaint feels a little abstract, and I’m sure Facebook will argue as much in court. It’s hard to weigh the value of Instagram and WhatsApp as they exist today against what they might have become had they remained independent, or been acquired by another corporation. But from the government’s point of view, that’s exactly the point: Facebook made the market less competitive, and now we’ll never know.

And two big points which belies the government’s ignorance of how technology works:

1. Instagram’s strength comes from network effects that are internal to Instagram. You don’t use Instagram because it’s owned by Facebook, and changing its ownership would not lead to more competitors. In much the same way, if Youtube became a separate company to Google, that wouldn’t lead to a wave of new video-sharing services. These products are not bundles.

2. So now you have Instagram and WhatsApp competing with each other. Which means they’d have more revenue pressure (especially WhatsApp!) and they would have less leverage with advertisers and more financial incentive to erode privacy. And would they be more keen to partner with new entrants, or to copy and squeeze them out just the same? Indeed, we have a great privacy counter-case in Tiktok, which exploded to 100m users in the U.S., prompting a panic that was mostly about … well, privacy. Tiktok is an entirely new company that Mark Z hates because on any measure made the market more competitive – and less private. Competition produced less privacy. Be careful what you wish for, Mr. Government Regulator.

I think the government’s case has a hard road ahead of it. The lawsuit would have felt much more vital two or three years ago. In the time it took the government to flesh out these arguments, many of which have been made in some form since at least 2014.

And speaking of TikTok, the government argues that apps like TikTok aren’t relevant to the market:

“Personal social networking is distinct from, and not reasonably interchangeable with, online video or audio consumption-focused services such as YouTube, Spotify, Netflix, and Hulu.”

TikTok itself is never mentioned. And the idea that these apps are not interchangeable would be news to Facebook. To quote Benedict Evans:

Market definition is always self-serving, but this market definition by the FTC is real gerrymandering. But, again – argue about that with a lawyer. Do you really want to die on a hill arguing that Facebook doesn’t have market dominance in social in the U.S.? Of course it does. But that it has no competition? Ah, that’s a stretch.

There were lots and lots of excited Tweets in my timeline from critics and lawmakers suggesting this could be the beginning of the end for Facebook. And the Financial Times exuberantly stated that Facebook was facing it “Standard Oil moment” when, over a century ago, U.S. antitrust regulators ordered the break-up of Standard Oil.

Ah, no. And I need to mention zeitgist again which will conclude this post. The monopoly on connectedness is obvious. But this noxious concentration of market power is also an unintended consequence of QE: cheap money boost share prices and cheapen debt, making acquisitions almost cost free. Big Tech has taken big advantage of this to bulldoze competition and grow its infrastructure of clouds, data warehouses and logistics centers.

But while I expect that this will mark the start of a painful period for Facebook, I’d be surprised if the resolution of this case weren’t much less dramatic.

Every generation of Tech has faced its “Standard Oil Moment”. Microsoft faced its and changed how it operated to defer any judgement. IBM faced its, changed how it operated to enable innovations like the “clone” market (mainframe compatible competitors), 3rd party application service providers (EDS), both from litigation. ATT, MaBell, was split up enabling cheaper long distance calls (MCI), regional competition and mobile competition. So now it’s the turn of FB and Google to face theirs.

Best book to read: “Goliath” by Matt Stoller which details the entire U.S. history of financial concentration in the hands of a few and the struggle between monopoly and democracy and regulation. I had the opportunity to interview him. More to come next year.

I am betting on self-imposed change à la IBM and Microsoft, versus the judicial hammer, à la ATT. Just like Bill Gates and Tom Watson, Mark Z will swallow his ego to keep his baby more or less intact.

Eventually the regulators will “get it”. The big shifts in dominance in tech in the last few decades have not generally come from a new product that does the same thing as the old one, but from a company doing something that changes the field of play. Microsoft didn’t overturn IBM’s dominance of mainframes – instead, PCs made mainframes irrelevant. Google didn’t make a new Windows, and Facebook didn’t take on Google at web search – instead, they carved out something new.

And as for MisDisMal … MISsinformation, DISinformation and MALinformation .. the internet doesn’t coddle you in a comforting information bubble. It imprisons you in an information cell and closes the walls in on you by a few microns every day. It works with your friends and the major media on the outside to make a study of your worst suspicions about the world and the society you live in. Then it finds the living embodiments of these fears and turns them into your cell mates. Everyone participates in the culture, even if they don’t want to participate. MisDisMal is not like a plumbing problem you fix. It is a social condition, like crime, that you must constantly monitor and adjust to.

END GAME? The multiple ongoing lawsuits and proposed regulations – related to antitrust in the United States, and data privacy and competition in the European Union – will slow down big tech. The U.S. case against Microsoft famously caused it to miss the threat posed to it by the internet; Sundar Pichai and Mark Zuckerberg will have to be on guard for the distractions that these cases could bring. (They’re students of Silicon Valley history, and so I imagine they already are.) Still: look for a slower pace of innovation and acquisitions than we might have seen otherwise.

VI. TikTok

Click on link above to meet my new spiritual muse, met on TikTok

Right now, for me, the only new entertaining motion pictures are shot by Leninist teens on TikTok. It’s not quite the breeding ground for innovation that Vine was, but it’s something. I have been on the site for well over a year. I sure hope someone somewhere is archiving it all.

I recently received a commission to write a monograph on TikTok so this section will be relativity short as I keep most of my powder try for the detailed exposition to come.

In these times of quarantine and rioting, moving images have stopped following their regular internet-era rules, which were already on shaky ground. We suffered through “Tiger King” and a string of forgettable rom-coms on Netflix. Oh, yes, and there has been some brilliant stuff: “The Queen’s Gambit, David Attenborough’s trip down memory lane in conjunction with his just-issued autobiography, and the gripping 3-part series on the Challenger disaster.

Still, over these past few months, the real good stuff, the most compelling stuff I found was on TikTok. It is not your *normal* social media platform. Engaging with potential customers in a place where they go to be entertained requires a nuanced, careful approach. Much of the site’s content is comedic – kind of like Vine, Twitter’s late video network (rest in peace). Some of the most popular genres include short skits, lip-syncing, cringe videos, and cooking how-to-do-its. I have spoken to so many “social media marketers” that completely missed the curve on this one.

Dancing teenagers all over the world are straining to fit the narrow dimensions of their phone cameras. Unlike the expansive style of a trained dancer, their movements are tight and tapered. The dances are deceivingly achievable, as though one could step into the routines without much thought. The dancers’ casual nature is brilliant. It is reminiscent of a time when the public happened to know specific dances no matter how dressed. On TikTok, these performances range from lackluster to expert – and might lead to virality, but that’s not the point.

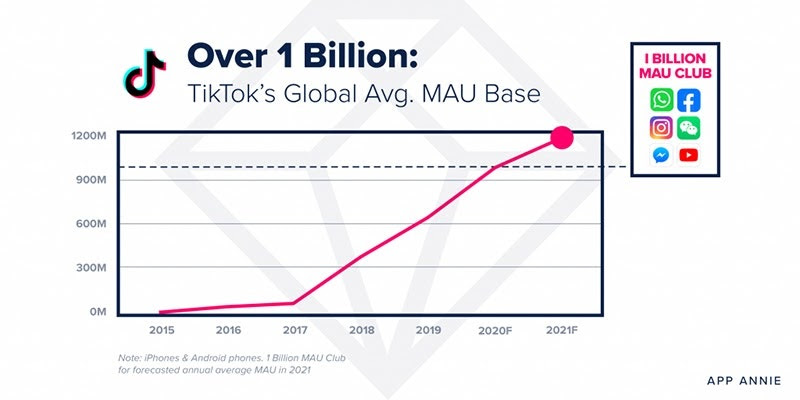

TikTok’s base, the fastest growing of all social media services, has exceeded a billion users. This flood of attention and content has brought the platform under intense global scrutiny. Pakistan has banned TikTok on the grounds that its user-generated content is immoral. The United States has argued that TikTok is a contemporary Trojan Horse, allowing ByteDance, TikTok’s China-based parent company, access to the private data of American citizens.

The global fuss over the platform is at odds with its standing as a virtual haven for young people. Given the smoke and mirrors of the present US/China trade war, perhaps it’s better to view TikTok from the vantage of its teens and the culture they create. This means understanding the platform as a curious aesthetic hybrid, designed in China and populated, more and more, by American users. Now quarantined in their bedrooms, its teens nurture a multidisciplinary skillset that leans on enigmatic charisma, quippy humor, and a knack for editing. They conjure narratives from nothing and package them within a minute’s timeframe. As TikTok rapidly proliferates, its aesthetic influence – in all its splendor and conformity – can be seen beyond the platform.

And confusion about TikTok’s aesthetic is to be expected. It mutates rapidly. There is an entire genre of TikTok videos dedicated to demystifying its algorithm, and even its popular users are uncertain about which content the platform favors. It happens from the moment you open the app for the first time: like many social media platforms, TikTok records its users’ preferences, shaping them into an amorphous “For You” page populated with videos it decides you might share or like.

BUT … unlike other social media, TikTok’s range of video types is highly personalized from user to user, and its endless-scroll feature creates the effect of falling down a rabbit hole without a clear exit point. Adding to TikTok’s inscrutability is the way it suppresses content from users who transgress its elusive standards.

Though we have seen this from every platform, allegations of racism and censorship against the service run rampant. In the past year Tiktok has attempted to distance themselves from the Chinese government, though it still falls under its strict policies and regulations. From country to country, censorship on the video app can range from LGBTQ+ discrimination to the blocking of social justice messages. This has meant that even popular TikTok users will have their videos deleted before receiving notice that their livestreams or posted content violate TikTok’s community guidelines. The reasons for this can range from appearing to support drug use to something as innocuous as using a curse word.

What’s more, if a user creates several videos that do not receive as much engagement as their previous posts, it is common for them to become paranoid, believing that they have been “shadowbanned.” As the term implies, the reasons for this ban – which is understood as a reduced number of views to a user’s videos – are not disclosed to the TikToker in question. What Tiktok suppresses can often tell us why, as an audience, we must be critical of large, influential platforms. It also helps explain why TikTok’s content and aesthetic are always in flux yet strangely in line with whatever the platform deems acceptable in that very moment.

What is more clear is that TikTok shifts the visual dialogue away from the perfectly manicured aesthetic of Instagram, which is known more for its users’ aspirational, flawless image curation. TikTok instead privileges on-screen presence, performance, and bite-sized narrative. Originality is not prioritized. Videos that start trends are often outdone by other users’ videos – it’s all in the execution.

Hence Mark Z hates it and has sided with attempts to limit, control, or kill it.

Jackie Maybex, a brilliant social media analyst at Ogilvy (ok, she gets me a free pass to attend Cannes Lions) says:

It is, compared to other social networks, a lottery that relies on the Warholian aphorism about fame for fifteen minutes. With each video posted, a lottery ticket is tossed into the ether, which is why experts discourage the deletion of videos—older content may yet find its place in the sun. In this respect, TikTok further rewards the never-ending churn of production. One of the platform’s most effective moves was to distinguish its users as “creators.”

The aesthetic of these creators does not easily cross platforms. During recent weeks, when it seemed likely that the app would be banned in the United States, TikTok celebrities pleaded with their audiences to follow them on Instagram. Though, by visiting a TikTok star’s Instagram page, one is immediately struck with how banal and serious the grid seems. It is clear that the spirit and charisma of these stars does not translate to an image-based app—the stationary images having the same effect as a eulogy.

The way TikTok rapidly produces hit songs, fashion trends, and teen icons feels somewhat like MTV in the 1990s and 2000s. The difference is that TikTok’s content is largely created by the same generation that consumes it. Most importantly, it feeds on the unserious day-to-day nature of being young. If Twitter is the surly critic, Instagram the polished and distant beauty, TikTok is the carefree youth. Well, for now.

And it, too, is waiting in the wings for initial public offering stardom.

It is expected to hit a billion users in 2021, which represents a three-fold increase in users since 2018. ByteDance, TikTok’s owner, plans to IPO the short-video thing. The weird graph above belies the reality that Tiktok got to a billion MAU (Monthly Active Users) in half the time of Facebook or Instagram.

VII. America is a bizarre show

It is difficult to write about America because although I am no longer a U.S. citizen I find myself irrevocably tangled in America’s hopes, arrogance, and despair. I am still “American” at heart, I suppose. I moved to Europe 20 years ago but still spent huge chunks of time in the U.S.

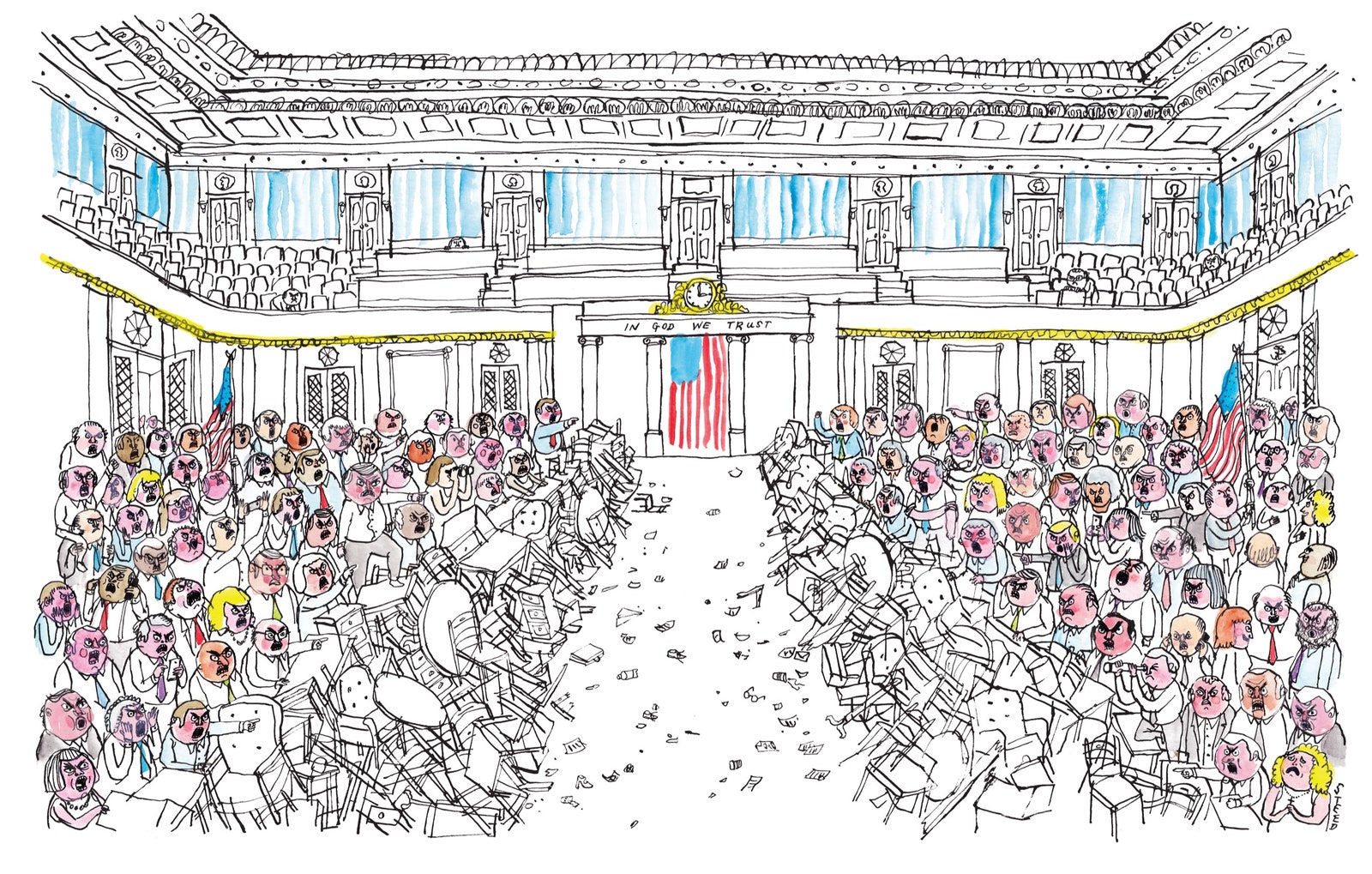

The stark polarization of American politics beyond this year’s immediate health, economic, racial, and electoral legitimacy crises corresponds to sharply contrasting apocalyptic visions of the future. For those on the right the looming nightmare is demographic, namely that by 2040 white Americans will constitute a plurality but no longer a majority of the population. To prevent the emergence of a truly representative, multiracial democracy that would mean the end of “their” America, they resort to census distortion, voter suppression, gerrymandering, uncontrolled campaign financing, sharply curtailed immigration, and now even the threats to intimidate voters through “armies of poll-watchers” and to “get rid of” mail-in ballots. These measures in turn build on the systemic tilt to the right that the Constitution currently provides to red states through the Electoral College and Senate.

As the 2020 dystopian election campaign unfolded, my mind kept being tugged by Plato’s Republic and The Federalist Papers, two things I re-read during the lockdown as part of my research for this piece. The Donald emerged from the populist circuses of pro wrestling and New York City tabloids, via reality television and Twitter, to prove not just Plato … who said “tyranny is probably established out of no other regime than democracy” … but also James Madison who said democracies “have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention … and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths”? Trump tested democracy’s singular weakness — its susceptibility to the demagogue — by blasting through the firewalls we once had in place to prevent such a person from seizing power.

Plato, of course, was not clairvoyant. His analysis of how democracy can turn into tyranny is a complex one more keyed toward ancient societies than our own. His disdain for democratic life was fueled in no small part by the fact that a democracy had executed his mentor, Socrates. And he would, I think, have been astonished at how American democracy has been able to thrive with unprecedented stability over the last couple of centuries even as it has brought more and more people into its embrace. It remains, in my view, a miracle of constitutional craftsmanship and cultural resilience.

The thing is that part of American democracy’s stability is owed to the fact that the Founding Fathers had read their Plato. To guard our democracy from the tyranny of the majority and the passions of the mob, they constructed large, hefty barriers between the popular will and the exercise of power. Voting rights were tightly circumscribed. The president and vice-president were not to be popularly elected but selected by an Electoral College, whose representatives were selected by the various states, often through state legislatures. The Senate’s structure (with two members from every state) was designed to temper the power of the more populous states, and its term of office (six years, compared with two for the House) was designed to cool and restrain temporary populist passions. The Supreme Court, picked by the president and confirmed by the Senate, was the final bulwark against any democratic furies that might percolate up from the House and threaten the Constitution. This separation of powers was designed precisely to create sturdy firewalls against democratic wildfires.

Madison, in the 10th Federalist Paper, written in 1787, argued that large republics were better insulated from corruption than small, or “pure” democracies. A large electorate on a grand scale would be more likely to select people of “enlightened views and virtuous sentiments”.

But what we got was a large electorate dominated by a tiny faction. What Madison could not have foreseen was the extent to which unconstrained campaign finance, a sophisticated lobbying industry, and a media/entertainment obsessed culture would come to dominate an entire nation.

And most amusing (if that is the appropriate word), is that the racism, xenophobia and violence of Donald Trump’s presidential campaigns was widely seen as an aberration, as if reasoned debate had been the default mode of American politics. But most have forgotten their U.S. history (or simply never read it) because precursors to Trump do exist, candidates who struck electoral gold by appealing to exaggerated fears, real grievances and visceral prejudices.

Technology does figure in all of this. Paul Hilder was right. “The Revolution will be Digitised”. The title of his book. Despite the events of 1989 (the fall of the Berlin Wall) and 2016 (Trump’s election) being decades in the making, they managed to catch experts unawares. After the Berlin Wall came down, western cosmopolitans and technocrats raced to claim victory. Yet beneath the euphoria of the New World Order, our own contradictions were festering – stagnant wages, gaping inequality and a feeling that most people had no real control over their lives. Another quarter of a century passed before the other shoe finally dropped. It was only in 2016 that most realized the rules of politics had been upended, in no small part, by new communication technologies.

Too late was it seen how costly and sophisticated data analytics enabled some plutocrats to buy influence from the shadows. Read Josh Ramo’s In The Seventh Sense (incidentally he’s Henry Kissinger’s business partner) which he published in 2016, and he described in detail the political effects of network power enabled by the new communication technologies. He highlights how the new political order is based on “frictionless many-to-many communication, from email lists to social networks and instant-messenger groups” that would enable people to find allies in an instant.

There is no “we” in America, he wrote. There is only kin and tribe. The technologies would place and amplify a person’s political beliefs at the center of their identity. Oh, it may be destructive for a civil society and undermine our sense of solidarity. But extensive analyses of polling data and election surveys showed that political beliefs are an effect, rather than a cause, of group membership and that people select their political party first and then adapt their political views to match those of their chosen tribe. This helps explain why our views on issues like climate change are best predicted by group membership but are unrelated to scientific literacy. Tribes advertise identity, not thought, and over-identifying with a particular political party subordinates individuals to group membership. The mission becomes advancing the interests of the imagined group and placing those interests beyond good and evil.

And when you have unlimited amounts of money and the power of data analytics, you can match voter rolls to their Facebook profiles, and used that platform’s “Lookalike Audiences” function, which identifies people whose profiles are similar to those of existing supporters.

Trump may be out of power but Trumpism ain’t disappearing. Elite populism and its big-data war machine will continue its attack on American democracy. It will continue to carpet bomb the electorate. Enter Trump: America’s first shadow President.

The election may be over, but the political influence of the former commander-in-chief is not. And with a $300 million kitty, raised from his supporters based on his “I-need-money-to-fight-the-hacked-election-I-won!”, he has a lot of fire power. He’ll engage in scorched-earth tactics to cripple the Biden administration, so he can better position himself ahead of 2024.

COVID certainly brought home that war over whether “American exceptionalism” exists is over. The idea has been battered beyond recognition by more than a decade in the gladiator ring of American politics. The term has so many meanings that it has no meaning. American exceptionalism was an honorable idea that deserves to be put on a stretcher.

The most intriguing pieces I have read about American politics this year were those analyzing how Trump had been “constructed” over 50 years, and how he was merely the next stage in a long history. The best piece, though dated, is by Lewis Lapham (click here).

The most mendacious of Trump’s predecessors would have been careful to limit these thoughts to private recording systems. Trump spoke them openly, not because he couldn’t control his impulses, but intentionally, even systematically, in order to demolish the norms that would otherwise have constrained his power. To his supporters, his shamelessness became a badge of honesty and strength. They grasped the message that they, too, could say whatever they wanted without apology. To his opponents, fighting by the rules—even in as small a way as calling him “President Trump”—seemed like a sucker’s game. So the level of American political language was everywhere dragged down, leaving a gaping shame deficit.

How did half the country – practical, hands-on, self-reliant Americans, still balancing family budgets and following complex repair manuals – slip into such cognitive decline when it came to politics? Blaming ignorance or stupidity would be a mistake. You have to summon an act of will, a certain energy and imagination, to replace truth with the authority of a con man like Trump.

IMPORTANT SIDE NOTE:

A few hours before the inauguration ceremony, the prospective U.S. president receives an elaborate and highly classified briefing on the means and procedures for blowing up the world with a nuclear attack, a rite of passage that a former official described as “a sobering moment.” Secret though it may be, we are at least aware that this introduction to apocalypse takes place.

But at some point in the first term, there is an even more secret briefing occurs, one that has never been publicly acknowledged. In it, the new president learns how to blow up the Constitution.

The session introduces “presidential emergency action documents,” or PEADs, orders that authorize a broad range of mortal assaults on our civil liberties. In the words of a rare declassified official description which surfaced three years ago, the documents outline how to “implement extraordinary presidential authority in response to extraordinary situations”—by imposing martial law, suspending habeas corpus, seizing control of the internet, imposing censorship, and incarcerating so-called subversives, among other repressive measures”.

These chilling directives have been silently proliferating since the dawn of the Cold War as an integral part of the hugely elaborate and expensive Continuity of Government (COG) program, a mechanism to preserve state authority (complete with well-provisioned underground bunkers for leaders) in the event of a nuclear holocaust. Compiled without any authorization from Congress, the emergency provisions long escaped public discussion — that is, until Donald Trump started to brag about them: “I have the right to do a lot of things that people don’t even know about,” he boasted in March, ominously echoing his interpretation of Article II of the Constitution, which, he has claimed, gives him “the right to do whatever I want as president.”

This really is one of the best-kept secrets in Washington and NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice did a long briefing note on them this past year. Trump used them to the max. He had a separate White House that just focused on exploiting them. It’s president’s hidden legal armory, and the Brennan Center assembled its brief by tracing stray references in declassified documents and obscure appropriations requests from previous administrations. I will have more in my full monograph.

Hannah Arendt, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, describes the susceptibility to propaganda of the atomized modern masses, “obsessed by a desire to escape from reality because in their essential homelessness they can no longer bear its accidental, incomprehensible aspects.” They seek refuge in “a man-made pattern of relative consistency” that bears little relation to reality. Though the U.S. is still a democratic republic, not a totalitarian regime, and Trump was an all-American demagogue, not a fascist dictator, his followers abandoned common sense and found their guide to the world in him. His defeat won’t change that. In fact, as we have seen this last month, it has recharged them.