Moving images bombard our brains and fog our thoughts. But every now and then they expand our minds.

The above is an abstract photo/illustration created by Elena Lacy. Copyright: GETTY IMAGES

13 December 2020 (Paris, France) – This past summer I wrote a very long post celebrating the video phone turning 50, and celebrating all the ways that video was going to make an exponential leap.

Tip to those of you who do video work, engage in video chats: buy yourself a ring light. You’ll look good and reduce “Zoom fatigue syndrome”. For more, click here. Have a larger budget? Buy yourself a few Aputure Light Storms. I just installed two in my new production studio at home which I’ll unveil in January. They’ll set you back €1,100 each but you’ll look like you are sitting in a BBC studio.

That post was part of a series I was developing with my media team: examining the coronavirus lock-downs and related disruptions vis-a-vis what this was doing, both affecting technology and effecting technology (a wide range, across many subject areas). In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted every organization on the planet. However, the outcome was not and will not be a retreat from Industry 4.0 – the implementation of automation, big data analytics, machine learning, and high-speed networking – but more rapid and permanent adoption of such critical technology.

But in fits and starts, the way most things work, and this was so clear with video. The patterns were all too familiar. We always start by making the “new” tech fit the existing ways that we work. We were taking/are taking post-COVID “new new” things and applying them to the “old old” ways we used to work and live. As I noted in that piece:

Video calling has perhaps become so normalized that we no longer think of it as particularly special. We’re in this moment now where the window in which this was a spectacular, futuristic technology quickly compressed into a kind of mundane ubiquity. Now it’s just another utility. It’s an essential action that is routine, so it’s lost some of that aura of grandeur.

But we need to understand the power and opportunity of video, beyond the development of video phones and video calls. Long-form and short-form video is now the most popular content format regardless of screen size, according to the latest “Video Index” from Ooyala, a company that has been at the forefront of understanding the ecosystem of online video platforms. I have used their video analytics and monetization solutions for years. They are among the best in the business. Video currently accounts for 70% of all internet traffic. Video dominates rich media tactics for online and direct marketing professionals, becoming the virtual “calling card” for marketing companies across all industries.

At the beginning of this year we were deep into a wave of “new productivity” software – dozens of new companies trying to remix some combination of lists, tables, charts, tasks, notes, and light-weight databases with collaboration, chat and sharing. All of these things are unbundling and rebundling spreadsheets, email and file shares. Instead of a flat grid of cells and a dumb list of files and messages, we get some kind of richer canvas that mixes all of these together in ways that are native to the web and collaboration.

And of course, we added video, and video is another candidate for remixing, and for asking what you’re trying to do. Zoom does a great job of getting you into the call, but doesn’t ask what the call is for. Why, exactly, are you sending someone a video stream and watching another one? Why am I looking at a grid of little thumbnails of faces? Is that the purpose of this moment? How do serendipity and unstructured creation work in a 30 minute call with pre-specified people at a pre-specified time? Are video, audio or synchronous communications even the right way to do that?

Hence, the other story in productivity is companies unbundling some specific workflow out of a general purpose tool – Figma or frame.io unbundle UI design and video from Photoshop, file shares and Google Sheets into dedicated products. That’s as old as the software business, but these companies are showing that there’s now almost nothing that can’t be converted from local software to the web.

And that’s the thing. What will happen to video is what is happening to voice. Everything has voice or is getting voice. Do a market map today of which apps on a smartphone or Mac or PC or IoT device have voice or might get voice. It would be absurd. Everything can have voice. And though there’s still a lot of engineering under the hood, it has become a commodity. What matters now is only how you wrap it.

This is where we’ll go with video. Yes, there will continue to be hard engineering, but video itself will be a commodity and the question will only be how you wrap it. There will be video in everything, just as there is voice in everything, and there will be a great deal of proliferation into industry verticals on one hand and into unbundling pieces of the tech stack on the other.

I address all of these issues in depth in that post (here is the link again). But my focus in that first post was on business applications. To my regret, I only skimmed over the political and social externalities caused by videos which are far more important. So let me finish that part of the conversation.

We will look back at 2020 as the year of maximum screen time. Severed by the pandemic from face-to-face interactions, we have been chained to our devices, making more video and watching more video than ever before. This ubiquity of moving images – this videocracy that first took shape during the early 2000s, with the rise of data-connected phones, Facebook, and YouTube – has become the chief way many of us view the world. And it’s dangerous. We anchor our public debates on video. We make judgments based on moving images and truncated sounds. They guide and structure the consideration of our public concerns.

Video is clever. It resists thought. It breaks linear modes of argumentation and resists complexity, containing all within a frame often now the size of a human hand. Videos can mislead us even when they aren’t clearly false or fraudulent, dangerous or destructive. Even those we might consider “news” or “documentary” may be a form of propaganda, compressing and distorting events, stories, and issues.

As I noted in my earlier post referenced above, the propagandistic effect was most acute when the moving image was new. A film like Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), for instance, once could draw viewers into its embrace with an erotic idealization of the “Aryan” body and allusions to classical empires. Audiences in the 1930s didn’t have the language or the tools to understand these tricks. They could not stop a film to study it, then rewind and watch again. They didn’t have the armor made from decades’ worth of criticism, the hard-earned knowledge of the risk: that video can undermine and overwhelm collective thought.

When I was taking film courses at New York University, Riefenstahl was considered a cinematic genius. At the U.S. Academy Awards in 2003 Riefenstahl was honored as one of the greatest filmmakers of her time. The Academy was reviled for honoring a woman who had been so heavily involved with Hitler.

I took several in-depth programs on her work. There is no end to what made her a legend. She perfected the idea of placing the viewer in the location of an “ideal spectator” at the beginning of an event, in her case a rally, a technique widely imitated today. She also perfected several narrative forms, displaying truly remarkable originality. There are some shot sequences that include approximately ninety shots within about five minutes. Thus, the shots are only about three seconds each. But the effect on the viewer is incredible. You can actually retell the “story” you saw. In “Olympia,” she looked for individual human effort: physical strain depicted through pulsing temples, bow-tight muscles. The point? People performing greatly, rather than how great their performances may have been. Riefenstahl also used a variety of camera angles, and three-second shots, when shooting the eye contact between Hitler and members of the cheering crowd to construct the idea of their bonding.

To arrive at a fair assessment of the woman and her talents is not easy. In the literature surrounding this enigmatic presence in film history, several Leni Riefenstahls appear. To judge from the scholarship about her, it is evident that she meant different things to different people.

We’re more sophisticated now, but the risk has not subsided. If anything, it has increased exponentially. The rapid, global proliferation of digital video, from around 2005 up through the present, makes it harder to sort and contextualize what we see – to think about, through, and with video. We may now resist the clumsy, overbearing propaganda of Olympia, or of any other single piece of video, but we’re more susceptible to the barrage of subtler, less bombastic messages that flow around us, each unworthy of attention yet influential in the aggregate.

These are all these streams – a torrent of stimuli. In the form of our phones, we all have Times Square in our pockets. It’s the environment that distorts reality now. Siva Vaidhyanathan, the cultural historian and media scholar and professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia who I had the pleasure to meet last year:

The overall effect is of cacophony: a vast, loud, bright, fractured, narcissistic ecosystem that leaves us little room for thoughtful deliberation. It’s not that we’ll believe the latest Covid conspiracy video (although too many people do). It’s that seeing video after video after video after video renders us unable to judge. They’re all making contradictory claims; they’re all just slick enough to make plausible demands for our attention and respect. We find ourselves numbed by overstimulation, distracted by constant movement and sound, unable to relate to those ensconced in different bubbles and influenced by different visions of reality. We can’t address our problems collectively in the face of this montage. We can’t mount cohesive and convincing arguments with ease or confidence. We mistrust everything because we can’t trust anything.

That’s not to say collective, collaborative thought is impossible in the age of ubiquitous video. It just means that we have to try harder, that we must construct better methods to defuse propaganda with deliberation. I’m not sure we can do this. But the events of this past spring and summer, when a single viral video seemed to move the world toward justice, gives me cause for limited optimism.

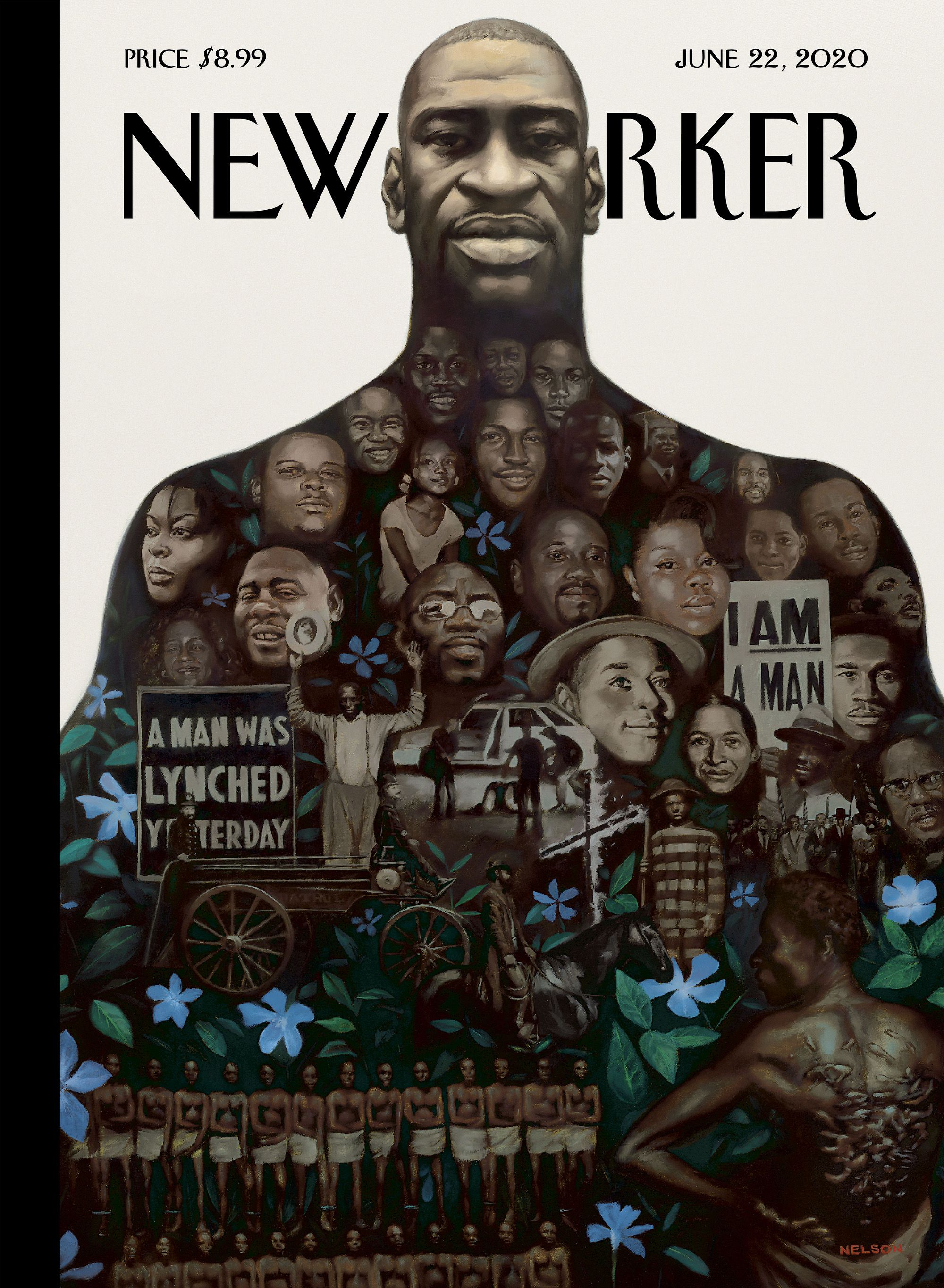

The powerful New Yorker cover that paid tribute to black lives lost

The powerful New Yorker cover that paid tribute to black lives lost

The footage capturing the last eight minutes of George Floyd’s life, as a Minneapolis police officer crushed it out of him on 25 May, launched a remarkable, transnational movement for racial justice. Like Eric Garner, who died at the hands of a New York City police officer in 2014, Floyd had his public execution by asphyxiation documented by a bystander recording on a mobile phone. The moving images and sounds quickly wrapped the globe, puncturing illusions, igniting latent frustrations, and propelling millions out into the streets.

Floyd’s death was captured by raw video. Its truths were impossible to deny. The officer’s voice was clear. Floyd’s voice was clear. The bystanders’ voices were clear. The image was clear. It was more powerful than any video of police brutality that came before, and yet it also built upon them all.

Now think back to Rodney King. George Holliday just happened to be one of the few Americans toting a portable video camera in 1991, and he just happened to be there to capture King’s beating by Los Angeles police officers on a grainy analog videotape. Stirring demonstrations broke out all over the country, along with riots. Commissions and studies of police violence followed and were quickly forgotten.

We had the opportunity, back then, to convene and deliberate seriously about the constant plague of racially motivated police violence. But the “national conversation,” as some proposed to call it, had gotten focused on one person, one event, and one poor-quality video. That made it all too easy to dismiss, as if the pattern of injustice were somehow not yet fully clear.

The elements of that pattern are now laid out for everyone to see, in one video after another of Black people’s mistreatment by police. Today, paradoxically, the very profusion of such videos has helped us in this moment to deliberate on greater, broader questions; not just on one story but on all the policies behind it.

The same cacophonous media environment that tends to dazzle and confuse us – that stupefying video-after-video-after-video-after-video effect – in this case yielded clarity. Video resists thought, but it does not prevent it.

I’ll close out with Siva Vaidhyanathan again:

The footage of Floyd’s death forced the issue with its length: dreadful and transfixing, a format that invited contemplation. If this principle could be extended – if we could learn to harness our attention, discipline ourselves, and focus—then perhaps we’d have a chance to curb injustice on an even grander scale. With cameras everywhere, we have a lot of evidence from which to draw.

But it will take work. The torrent of video never stops battering our minds. For thought to prevail, it will need to weather this downpour and push through to higher ground. No mean task in a visually saturated environment.