This is an updated version of the post sent out last night (in a rush) to my client and subscriber lists, eliminating (most of) the egregious typos and segues, adding a wee bit more history for perspective, and inserting several graphics missing from the original piece.

21 October 2020 (Chania, Crete) – Yesterday the U.S. government sued Google, claiming that the company is an illegal monopoly. The media issued a flood of stories that all seemed to blare “this is the U.S. government’s most significant legal challenge to a tech company’s market power in a generation” and “Google is in big trouble now”.

There is an awful lot to unpack from the complaint, and the antitrust law regime, so I will have a more detailed response next week. But the DOJ filing was timely, though, because it dovetailed with my just-completed paper on how the Google-dominated programmatic ad world works which you’ll all receive in due course. You can read the Department of Justice (DOJ) complaint by clicking here. The complaint does a nice job of outlining that ad world I wrote about (in fact, of the 60+ pages I think more than half is an ad tech “explainer” rather than the merits of an antitrust case).

Sections of the complaint leaked (deliberately?) over the weekend. As I noted in my brief to clients on Sunday, the Google legal case is going to be loud, confusing and will most likely drag on for years. More confusing lawsuits against Google from U.S. states are probably coming, too.

NOTE: two weeks ago the U.S. House committee released its anti-trust report, and the harshest version is signed only by the Democrats on the committee. Today, the DOJ unveils its suit against Google – and is joined only by Republican governors. I detect a mess coming.

THE KEY QUESTION: does Google break the rules to stay on top? And if so, does that hurt us? So, yes, this is about politics and legal minutiae, but ultimately this case boils down to whether the technology that we use could be better, and whether the American economy could be more fair. Or are we all just hunky-dory as things are now.

And the nagging question (well, besides the political timing): is the government suing Google because the government itself wasn’t doing its job? All of the activity that the Justice Department now says is evidence of Google maintaining an illegal monopoly over search and search advertising has been known for years and could possibly have led to a crackdown by agencies like the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and the DOJ. Those agencies are responsible for keeping watch on companies for signs of potentially abusive behavior. Under both Democratic and Republican presidents in recent years, Google faced few substantive government enforcement actions for anything it did that made the company stronger and harder to unseat. If you let your kid act up again and again without consequences, should you be surprised that it keeps happening?

That was certainly the conclusion of the House congressional investigation report released two weeks ago: America’s antitrust watchdogs had fallen down on the job.

But this was not behavior via a hush-hush conspiracy “cooked up in underground bunkers at Google headquarters” as tech write Shira Ovide wrote in her newsletter yesterday:

We’ve known for years that Google has paid Apple billions of dollars each year to make sure its search engine is the one that people encounter on their iPhones and in the Safari web browser. It’s not a secret that Google had contracts with phone companies that required them to include Google apps on smartphones and make its search engine practically inescapable.

And I have noted in numerous posts, the European Union’s antitrust regulators fined Google over similar tactics in 2018. The EU required changes to Google’s behavior, although some competitors have said they are ineffective. In fact, Google has brilliantly skirted the EU’s mandates – mostly because they were poorly written. The EU had no clue how ad tech worked. [See more below]

Just a few points:

Just a wee bit of history. If you have followed by posts through the years, you’ll recall that when Google was being sued by the European Commission (EC) in 2010 over its suppression of shopping comparison sites – beginning with the British company Foundem – we all thought the EC was making the right move, and focused on the correct topic: that Google was manipulating search to favor its own products over what consumers evidently wanted. Effectively, that’s annexation: using your power in the market to push others out of an adjacent market.

We all (pretty much) thought the EC lawsuit against Google over tying Google services to Android was reasonable, too. It’s a slightly different situation – an effective monopsony: Google’s the only useful supplier for Android that people want outside China (ask Huawei). The OEMs would all have to defect from Google to have any effect; and defection back would be more profitable.

But this DOJ suit? This is nonsense. There’s no law against being a monopoly in the US. The 1998 lawsuit against Microsoft was about tying the provision of Windows to the use of Internet Explorer – when browsers were a new technology. IBM nearly missed out on the whole Windows95 launch because it resisted. The FTC had an excellent chance to act on this right back in 2013 but whiffed it. If the DoJ and the states really want to make their case work, they should revisit that casework. But it wasn’t about being a monopoly. It was about suppressing rivals in shopping search.

The DOJ Google antitrust fling is very narrow scope – nothing on ads/bundling/self-preferencing at all. Purely focused on Traffic Acquisition Costs (commonly referred to as TAC in the industry), primarily TAC as paying for/obliging status as default search.

NOTE: the UK Competition and Markets Authority also called this out as a barrier to search competition. I Tweeted out that report over the summer which you can find here.

And look: network effects are natural monopolies. They are not based on the owner of the network trying, or doing mean things to other people (though they may well do that), and you can’t break them up, any more than you can break up a water system. You can only regulate them. Americans love to cite AT&T in this conversation: “Look! We broke it up!” Well, yeah, but guess what? You replaced a national monopoly with local monopolies and competition in local access didn’t change at all. Read your tech history, you morons.

And look: not every problem in tech is a competition problem. But where something is a competition problem, that doesn’t mean break ups will *work*. They’re often an eye-catching alternative to doing the hard work of analysis and regulation. So, do you want headlines, or solutions?

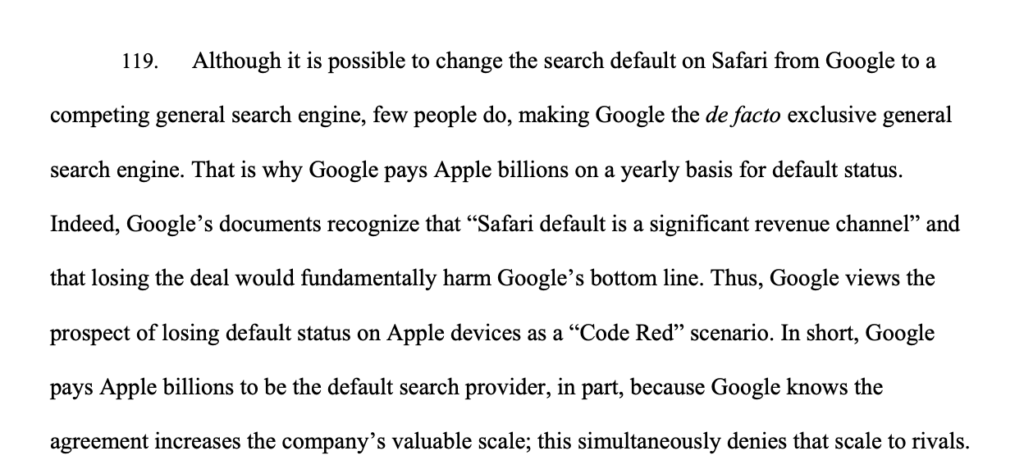

And parse the complaint. You get passages like this:

You could just as easily use this to argue that Apple uses its market dominance in the U.S. browser market to extort TAC from Google – and that Google is the victim and Apple the monopolist. Useful data point: the iPhone is 60% of Google’s mobile search in the U.S. , and 50% of all Google’s U.S. search traffic in 2019 was from iOS and MacOS.

Yes, there are very complex legal questions involved here. The government can’t just declare that Google “stop doing stuff like this” just because it makes the company stronger. I’ll address many of these points in my longer analysis next week. Let’s move on.

So on the morning that the DOJ formally sued Google for having an illegal monopoly over search and search advertising, Facebook took another step towards bringing its different companies – Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus, Messenger – all under one roof. As I have noted in many posts, Facebook has been slowly moving in this direction for a little while now. Last November, then-chief marketing officer Antonio Lucio explained why all of the different Facebook companies will now have the words “from Facebook” as part of each company’s brand:

People should know which companies make the products they use. Our main services include the Facebook app, Messenger, Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus, Workplace, Portal and Calibra. These apps and technologies have shared infrastructure for years and the teams behind them frequently work together.

That “shared infrastructure” is a key component to Facebook’s continued march towards end-to-end encryption, which beyond being a pretty difficult feat, would also potentially draw government pushback. From the New York Times, January 2019:

By stitching the apps’ infrastructure together, Mr. Zuckerberg hopes to increase Facebook’s utility and keep users highly engaged inside the company’s ecosystem. That could reduce people’s appetite for rival messaging services, like those offered by Apple and Google. If users can interact more frequently with Facebook’s apps, the company might also be able to increase its advertising business or add new revenue-generating services, the people said.

Fast forward to September of this year, as Facebook is under investigation:

The F.T.C. has not disclosed details of its investigation, but it appears the agency is partly focused on whether Facebook illegally maintained its dominance in social networking through acquisitions. The company has bought more than 80 companies over the last 15 or so years.

But as Google now has a date in Federal court to defend its practices, the click beast is unmoved. The Sacramento Bee News Guild took to Twitter to explain how its McClatchy executive team wants to tie journalists’ pay to the number of clicks their stories get:

This is not smart for several reasons. Obviously, journalists don’t get paid a lot to begin with, and incentivizing folks to get paid for clicks will create a race-to-the-bottom effect. It’s like media companies that stupidly slap a story quota to journalists with the idiotic thinking that more content equals more pageviews, which will get higher ad impressions.

Seriously, any company that puts a quota on journalism clearly is not in the journalism business but instead is just a glorified marketer. If you want to help your audience be smarter, don’t put quotas on journalists. Of course, this doesn’t mean that reporters should be sitting on their thumbs; a high metabolism is necessary for any newsroom.

The click was the original sin of the internet. It’s also why the web’s infrastructure is terrible: we incentivize companies to monetize through traffic, generated by clicks. That leads to folks gaming the system in several ways. One way: content farms that pump out shit content.

Why pump out so much shit content? Feed the search beast. The better the SEO, the more clicks; for reporters who break news and don’t have a solid SEO function, they wind up losing on all the potential traffic.

I’ll end with some concluding thoughts on the U.S. House Judiciary Committee’s report on the monopoly power and practices of the world’s largest technology companies which I had started here.

As I noted in my first piece, this enormous doorstop of a report … it’s a couple of thousand pages long, thousands of footnotes … took me 5 days to read and cross-reference. It was the culmination of a 16 month investigation by the House Antitrust Subcommittee. The staffers did a market analysis of how Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple operate. So it’s a little bit like an investment banking analyst report seen through an antitrust law lens. I think they were trying, foremost, to explain how these business models work, how the law shapes those business models, and then whether there are problems with competition or problems with democracy, economic problems or other other potential social issues that Congress should deal with or enforce: break them up, and if so how-when-where, or not to touch them – that kind of thing.

Just way too much to unpack from that report for this post so here are just a few highlights/thoughts.

• I think broadly speaking it was a report that largely focused on the need for new law and the need for Congress to start legislating, and the need for antitrust enforcers to start doing their job. That’s the main critique that they came out with, which isn’t so much that these are big, bad companies. It’s more that the law in general and laws against illegal mergers, laws against various forms of anti-competitive practices, etc. haven’t been enforced.

• In fact, they haven’t been enforced for decades, actually, almost from the origin of the firms under investigation. The weakening of antitrust law coincided with Milton Friedman and his supply side-ism. And that’s 1971 so that’s when the “intellectual property” was set. Companies simply built off the back of that. It was almost the perfect storm. You had a political revolution that took place in the early 1980s when Reagan rolled back enforcement, and the whole process gradually spread globally. And then you have the technological revolution that kind of came in with the Internet and then in the 1990s the merger of telecommunications and computing.

• So you have these large Internet businesses born into this legal environment, native-born monopolization. The legal environment in the 1990s was very favorable to monopolizing. That’s when Google, Facebook and Amazon were born and Apple a little bit earlier. But essentially, they’re all born native to monopoly. They’re also built on top of the technological revolution. These high tech companies were the steel and oil of their time.

And though this was not covered in the House report but is in my longer brief, you saw roll ups in the oil industry in the 1970s and then the steel industry in the 1980s and 1990s. That pattern was followed by tech. In the 2000s, you saw a roll up of thousands of companies – ad tech companies, infrastructure companies, mapping companies, search companies, and so on. They all got bought up largely by Google and Facebook and then Amazon.

• But these were businesses with distinctly different business models and capabilities and footprints and you can see the House committee was trying to grapple with this. And they were trying to figure out “fraud” and “manipulation” with businesses and business models that did not seem to fit.

• One thing that stymied the House committee was that there are a whole bunch of Supreme Court precedents that make it easier for corporations to engage in certain practices. And the House committee recommendation was “Congress needs to void out those decisions”. Not going to happen.

• A lot of attention was devoted to sector specific separation – the separation of platform and commerce. And the House committee recognized that the antitrust laws were ill equipped for that. Antitrust is a very specific, narrow body of law. The committee wants a law that says that if you have a platform that you’re not allowed to compete on top of it, you can’t be both the umpire writing the rules and running the platform and be a player on the field. And that’s, I think, what all four of the Big Tech companies have – this entangled platform-ish string of elements. But the separation of the application from the platform layer violates one of the very sacred beliefs within the technology industry.

• But here is my issue and I can only give it a quick scan. Anybody remember what all those direct-to-consumer app sites were like? Chaos. Now, you have the Apple App Store, where a would be app developer has no direct distribution as a consumer, and pays a terrible vig … sometimes 30 percent … to a network.

BUT … by having an App Store, for instance, designed and developed by Apple, we got trust. And consumers (and those software developers) saw the app market skyrocket. Now the House committee says “we must untangle this” but I see some enormous problems with how you choose to implement it and where you draw the lines.

* The House committee report is almost saying “we want public utility style institutions”. Which is to say “you are going to be an infrastructure, and you can’t leverage that into dominance in other areas”.

• Yes, there is a bit of history here, with the railroads and the Hepburn Act. Or television prime time. Or the financial syndication role. Or the airlines in the 1930s, which broke up Boeing and United Airlines. Even technology has done it (kind of) with data processing. So there is some history of separating platforms in commerce in other areas.

* But with the tech world today, lots of issues. The App Store came out in around 2007/2008 but the iPhone wasn’t a dominant platform. But now, there is half trillion dollars of commerce that goes through the Apple App Store. So it has a high level of importance that puts Apple in the position where it is.

* I do see the problem of monopolization. If there are other ways to buy to buy products, then you could say “well, they can sort of do what they want”. It’s when Apple became dominant the problem arose. Now, there is just is no way to get an app other than through the App Store. And if you are a developer, there’s no way to get your app on the iPhone independently. And so I think that’s where you have the political problem, the monopolization problem.

* And I wish I had the time but we also need to look at another reality. I seriously think there is a national security argument. Ultimately these companies are not just national infrastructure, they are global infrastructure.

Apple, Google and Microsoft were all approached by the U.S. Cyber Command re: cyber threats and the role these companies play to manage this infrastructure, connecting back not to an economic issue, but actually a security issue: that if you start to break these companies apart in that way, you actually increase the attack surface. You increase the risk, the entry points that malevolent actors have to get it to get in. It is more than Facebook doing a quality job moderating fake news.

Ultimately, their end to end control of the platform gives them much more control so that opening it up to “one and all” and all sundry characters means you give everybody access to what has become a utility infrastructure.

* And, yes, again, I am not stupid. I know the money that Google and Facebook make off spreading conspiracy theories. They just don’t have an incentive to address that. And they’re so big that they end up spreading this stuff to billions of people. And when you have such distributed systems, you lose civic leadership, you lose civic infrastructure.

I will conclude with these points:

-There are political conditions of monopolization, and also technological conditions towards monopolization. What’s different with these exponential age companies like an Amazon or a Facebook is that they are built upon intangible assets rather than the tangible, very variable cost type assets that you would have if you were building cars. And the nature of intangible assets is that they particularly when they’re protected as they tend towards market power. And that’s accelerated when you have AI and the data network effect, which is separate to the consumer network effect.

-So when I look at the underlying dynamics of how companies like this tend to grow, they do tend to grow in a outsized market share kind of kind of way. Look back at companies like GM. GM had 10 percent market share of the car business when it was at its biggest. Today, the smallest of these companies by market share is Amazon, which has 40 percent of the e-commerce space. It’s these huge technological underpinnings and processes that drove these companies to be to be big.

-I don’t think that’s a reason not to intervene. But there are complex dynamics at work here. We need to examine and distinguish between different kinds of economies of scale, operational and technical and innovative economies of scale and the necessary and legal structures.

-I think we’ll see legislators take the House committee report and shave off some of the more aggressive stuff. And they will go hard after Google simply because Google is so powerful and it’s impossible to ignore the market power that Google has. Same thing with Amazon, I think.

-I’ve left out the hindering of entrepreneurship and innovation, investment opportunities and jobs and all sorts of other problems. I have my limits 🙂

But this is merely the beginning of a global conversation. I’ve just started.