A short review on how the region’s new data protection rules have panned out two years after they came into force.

25 May 2020 (Brussels, BE) – The new General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) came about as a swipe against American Big Tech. Let’s not beat about the bush. The EU wanted to take them down a peg. So as Europe’s flagship privacy law celebrates its second birthday, a question still dogs regulators: Where is the big ticket enforcement?

Well, nowhere. As of today, Monday, the second anniversary of when the GDPR took effect, the EU will have handed out only two fines to Silicon Valley tech giants — the first to the local subsidiary of Facebook in Germany, for €51,000 and the second to Google in France over Android, for €50 million. Ireland dithers over its investigation of Google and Twitter, The Netherlands is still investigating Netflix, while Luxembourg’s privacy authority, which has jurisdiction over Amazon and Paypal among others, has yet to issue a single enforcement notice. Since May 2018, European privacy watchdogs have levied just under €150 million in fines in total over GDPR violations.

NOTE: to keep track, the GDPR Enforcement Tracker maintains a list and overview of fines and penalties imposed but advises “since not all fines are made public, this list can of course never be complete, which is why we appreciate any indication of further GDPR fines and penalties.”

The lack of action underscores some of the challenges facing the regulators tasked with ensuring Big Tech is compliant with the GDPR. While the tech giants stock their ranks with small armies of lawyers (plus large in-house teams: leaked emails at Google and Facebook indicate those companies each have 2,500 member teams to deal with the GDPR), much of the oversight falls to just one small, underfunded agency, the Irish Data Protection Commission, thanks to a quirk in European law. I’ll get to that in a moment.

I was fortunate to watch the entire four year GDPR gestation, living in Brussels and having contacts with EU Commission insiders. To watch the machinations of Big Tech was a Master Class in manipulation. And to hear the various regulators claiming to be “overwhelmed” and that this GDPR thing “dropped out of the sky” when they had over 2+ years to prepare, budget, and hire before the enforcement date of 25 May 2018 – and time to complain about preparation, budget, and staffing issues beforehand – was a Master Class in regulatory incompetence. Alas, not all of their own making. The bean counters surely are also at fault.

The fundamental problem was always the collection of data, not its control. Europe introduced the GDPR aimed at curbing abuses of customer data. But the legislation misdiagnosed the problems. It should have tackled the collection of data, not its protection once collected. As I reported several years ago, when the GDPR drafting first began, the focus was on limiting collection but Big Tech lobbyists and lawyers turned that premise 180 degrees and “control” became the operative word. That has always been Big Tech’s mantra: don’t ask permission. Just do it, and then apologise later if it goes bad. Zuckerberg is the poster boy for that mantra.

So when control is the “north star” then lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. It’s not clear that more control and more choices are actually going to help us. What is the end game we’re actually hoping for with control? If data processing is so dangerous that we need these complicated controls, maybe we should just not allow the processing at all? How about that idea?

Had regulators really wanted to help they would have stopped forcing complex control burdens on citizens, and made real rules that mandate deletion or forbid collection in the first place for high risk activities. But they could not. They lost control of the narrative. As I have noted in a series of posts, as soon as the new GDPR negotiations were in process 4+ years ago the Silicon Valley elves sent their army of lawyers and lobbyists to control the narrative to be about “control” – putting the burden on citizens. The regulators had their chance but they got played. Because despite all the sound and fury, the implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies know it is too late now (despite calls for a GDPR “rewrite”) to impose that structure so they will make sure any attempt at new rules that seek to redress any errors work in their favor.

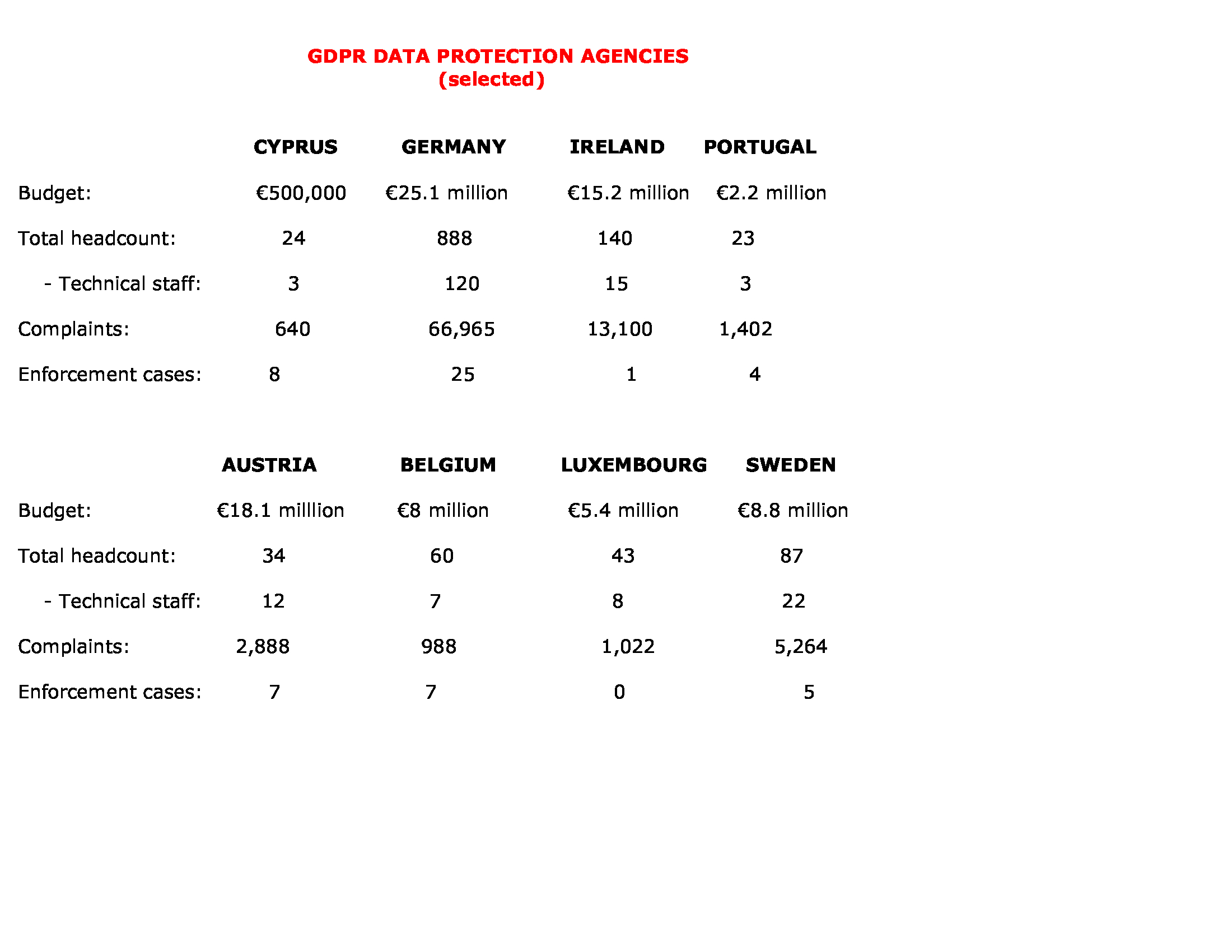

One theme unites all regulators, however – a lack of resources. Almost every EU agency is understaffed and underfunded for the job they have been tasked with under the new rules. Amazon’s global revenue exceeded €257 billion last year, but the Luxembourg authority overseeing its EU operations has a budget just over €5 million with 43 employees. The Irish watchdog’s annual budget of around €15 million is mostly pocket change compared to the billions earned annually by Facebook, Google and Microsoft. [see chart below for the headcount and budgets for a few other regulators]

Against that backdrop, it’s easy to see why watchdogs are cautious. Their legal firepower is no match for the deep bench of lawyers that international companies can throw at lengthy appeals. Such costly missteps are already part of the legal landscape. Record multi-million-pound fines announced last summer by the U.K.’s data protection authority have yet to materialise and look almost certain to be much lower than initially proposed. Courts have overturned privacy penalties in Poland, Belgium and Bulgaria, fueling worries within agencies of potential future missteps. In an interview a few weeks ago, European Data Protection Supervisor Wojciech Wiewiórowski noted:

One of the biggest mistakes that we can do is to go fast with some things and to lose it in judicial review. If we fail judicial review, not because of the merit of the case, but because of some formality that was done wrongly on the road for the lack of the process and the proceedings – well, we create disaster.

Collectively, EU regulators’ budgets to police and enforce the rules now stand collectively at about €300 million, an amount that Johannes Caspar, head of Hamburg’s data protection agency, called “peanuts”. He said it hampers the whole enforcement structure of the GDPR:

The system doesn’t work. Across all 27 EU member states we have collectively received almost 300,000 complaints, and they’ve been filed against everyone from Facebook and Google to mom-and-pop stores across our entire bloc.

Download the organisational charts of these data protection agencies and the list of complaints filed and you see the difficulty. Just to site a few:

I carved out the technical staff in the above chart (and note there are not many in any regulator’s headcount) because my biggest issue is the framers of the GDPR failed to understand how the digital economy/social sphere has been evolving in three phases: the “Internet economy” transformed into the “data-driven economy,” which in turn is transforming into the “algorithmic economy” – and our complex relationships to all of those phases. For that reason, the GDPR is really unfit for purpose.

It’s as I have noted before. There are actually three layers that companies hold.

1. Data you’ve volunteered

2. Data that’s been generated about you

3. Data that’s been inferred.

It is Layer 3 is where the action happens. This is what the tech companies fought mightily to preserve. This is the real “commercial layer”, the “inference data point” conundrum I have written about before. The company algorithms determine they have 30 given criteria data points, identifiably as “me”. But the 31st point has a likelihood of being something being true about me, but it is something they’ve calculated. It’s their intellectual property (IP). It’s not a personal data point. Big Tech is not in the least bit interested in “first person singular”. It’s Big Data they want. We are in the “probabilistic nature of data science” and the “inference” area. It’s an area where the consequential parts of our data existences are also the bits furthest away from our control or knowledge.

It’s why these “techies” were drafted in to help. Not heavily consulted in the drafting of the GDPR, they are being brought in now for enforcement analysis. Because the way data is being manipulated is changing, rapidly, and the change started about 10 years ago. One of the more commonly discussed ways is “graph”, which involves a switch in logic form that was not available to the general geek population (from linear to predication). And what has happened is the GDPR has become “the law of everything”. It’s drawing data protection authorities into making an awful lot of decisions that impact societies and individuals that appear to go well beyond simple data processing. These cases are becoming technically complex.

This all merits a much longer exposition which I’ll provide at a later date, enabled by a good mate, Allen Woods, once a chartered member of the British Computer Society who at one stage of his life was one of those people who had a whole alphabet after their name. He has nine major papers published one way or another by all sorts of organisations covering a variety of information management issues. Now retired, he has a lot of time to think and write so together we’ll bang out that longer piece. I’ll give him the last word:

The GDPR was written from the perspective of how big government manages data. And big government is strongly procedural and linear. Meanwhile the rest of the world has gone organic and viral. As indicated by things like “graph”.

Furthermore IT has been largely unregulated for the past 40 years. GDPR is just an attempt to catch up. And the rest, with variations on a theme, are catching up, too. That it is not working is indicated in spades, by the fact that key data protection agency are woefully under resourced. And using this regulation to resolve minor affronts (take the recent Netherlands case, for instance, regardless of the nuances) is only going to make things worse.

Meanwhile, the big cases are not being addressed in anything like the way they should be.

And to add insult to injury, as has been widely reported, many experienced data protection employees have left regulators either out of frustration and/or better pay at corporates, so you have a flood of newcomers coming into the regulators with little experience with privacy.

Part of the problem, which I have discussed in previous posts, is clunky cooperation between EU officials. Under the region’s new privacy laws, the watchdog where a company is headquartered is responsible for investigating all possible infractions by that firm across the bloc. But some authorities, notably those in Germany, have criticized the system as ineffective and ultimately unfit to protect Europeans’ privacy rights. They have suggested the creation of a pan-European regulator to rein in Big Tech. This was actually on Germany’s agenda (on 1 June, Germany will assume the presidency in the Council of the European Union and will thus guide consultations in the bodies of the Council for six months) but taken off as the COVID-19 crisis wiped out Germany’s intended agenda.

So any wholesale change is beyond the scope of the European Commission’s upcoming evaluation of the rules, which was expected on 10 June. I have seen a draft and all it seems we’ll get is a call for greater use of existing cooperation mechanisms, including a monthly meeting among regulators in Brussels.

And if you really want to break the regulators’ backs, the coronavirus crisis has piled extra pressure as governments have turned to data-gathering techniques from contact-tracing smartphone apps to thermal cameras for temperature checks to halt the virus’s spread. Regulators have offered vastly different responses to those activities. It’s too much to address in this post but in another of my works-in-progress I’ll try to explain:

• Big Tech has a lot of cheek pretending its “solutions” are privacy-friendly

• Countries are deploying “solutions” that are not certain to work, with the risk that they will cause other problems to develop

• This data can never truly be made “anonymous”

So regulators take a default position. Being overwhelmed, they have leaned heavily toward “engagement” – or doling out advice on how to stay legal – over investigations and enforcement, to look busy. Or as one regulator told me “we’ll go after small companies, the low-hanging fruit, because we can force them to settle quickly”.

And they struggle with a complete lack of transparency and cooperation between European data protection authorities that are meant to work hand-in-hand to enforce the rules, but end up being stymied by divergent national legal systems, cultural differences and an outmoded information exchange system. Worse, there are increasingly glaring differences in how EU watchdogs are interpreting the rules and, at times, breaking out of the one-stop-shop system to create what resembles a patchwork of privacy regimens instead of a single European landscape.

I’ve done three Zoom chats on the GDPR leading up to today. There are scores of points to make but there are two points that everybody seemed to agree with:

• Probes take time because the GDPR is completely untested and cases need to stand up to the scrutiny of all 27 EU nations, as well as in national court. Big Tech has the financial power to execute the long game. You’re going to see a battle over fines and remedies in arguments that could take years to untangle, and which will only get resolved by the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg.

• Ireland and Luxembourg have faced special scrutiny because so many U.S. tech companies have set up shop in those tiny nations, which have actively courted them thanks to a mix of low corporate tax rates and business-friendly regulation. Those close relationships have created a strong degree of economic dependency, particularly in the Irish cases, which raises questions as to whether these countries are best suited to regulating Big Tech. The German idea of creating a pan-European regulator might be the only solution. But Big Tech poured a lot of time and money power to get the “one-stop-shop” system … it was the most heavily lobbied element by the Big Tech lobby brigade … so expect a dog fight.

And the bigger picture? We are navigating … with a great amount of difficulty … an historic transition with digital technology and artificial intelligence. Our dominant storytelling must change. Silicon Valley people went from being heroes to antiheroes in the space of a few elections (2016 in the United States; Brexit in the UK). And when you talk with them, they are as confused as everyone else on how it all flipped. Because they aren’t different people nor are they doing things that dramatically different. It’s the same game as before.

The reality is that the problems that are causing so much turmoil in the world predate the digital and computational acceleration, but are also very much aided by it. It’s not either/or at all. The problem is the creators of all this wonderful technical infrastructure we live in are under social and legal pressure to comply with expectations that can be difficult to translate into computational and business logics. This stuff is about privacy engineering and information security and data economics. Dramatically amplifying the privacy impacts of these technologies are transformations in the software engineering industry – with the shift from shrink-wrap software to cloud services – spawning an agile and ever more powerful information industry. The resulting technologies like social media, user generated content sites, and the rise of data brokers who bridged this new-fangled sector with traditional industries, all contribute to a data landscape filled with privacy perils. You need folks that can fully explain the technical realities.

There is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships? As I noted above, when “data control” is the north star, lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. And the GDPR does not address these issues because its drafters did not understand or even recognise them. But the tech companies did.

Data protection is just one piece of the puzzle, and the GDPR is the floor, not the ceiling. Without effective competition and application … and big players can and will impose their terms and conditions on the treatment of data … and without sectoral privacy laws (the EU’s yet-to-be-finalized ePrivacy Regulation being just one example, and one far more important than the GDPR) it’s a mug’s game.

Big Tech will always take a close interest – and do everything in their power to steer construction of any new guardrails to their own benefit. Because what the GDPR misses is not the issue of data minimization but that these platforms exercise quasi-sovereign powers to actually institute a quasi-totalitarian rule across the many contexts we navigate. Data control was never the issue.