Ring smart doorbells mean more cameras on more doorsteps, where surveillance footage used to be rare

6 June 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) – Amazon has seemed hell-bent on creating a surveillance network, whether it’s through selling the FBI and law enforcement surveillance software like Amazon’s Facial Rekognition technology (now under fire by a government watchdog for its lack of privacy), or Amazon’s Ring’s video doorbell neighborhood surveillance network. Most of the focus has been on Rekognition technology. But it would appear we have missed the more immediate threat … that door bell.

There have been a flood of articles and blog posts on the subject so I have scanned the stack (yes, I still use “stack” to refer to my electronic reading) so this will be highlights of the major points from all sources.

While residential neighborhoods aren’t usually lined with security cameras, the smart doorbell’s popularity has essentially created private surveillance networks powered by Amazon and promoted by police departments. Police departments across the country, from major cities like Houston to towns with fewer than 30,000 people, have offered free or discounted Ring doorbells to citizens, sometimes using taxpayer funds to pay for Amazon’s products. While Ring owners are supposed to have a choice on providing police footage, in some giveaways, the police actually require recipients to turn over footage when requested.

In a press release earlier this week Ring said it would start cracking down on those “strings attached”:

Ring customers are in control of their videos, when they decide to share them and whether or not they want to purchase a recording plan. Ring has donated devices to Neighbor’s Law Enforcement partners for them to provide to members of their communities. Ring does not support programs that require recipients to subscribe to a recording plan or that footage from Ring devices be shared as a condition for receiving a donated device.

But many of the people in these neighborhoods receiving the Ring video doorbells say they don’t mind because more surveillance footage in neighborhoods could help police investigate crimes … even if raises questions about privacy involving both law enforcement and tech giants.

How it works

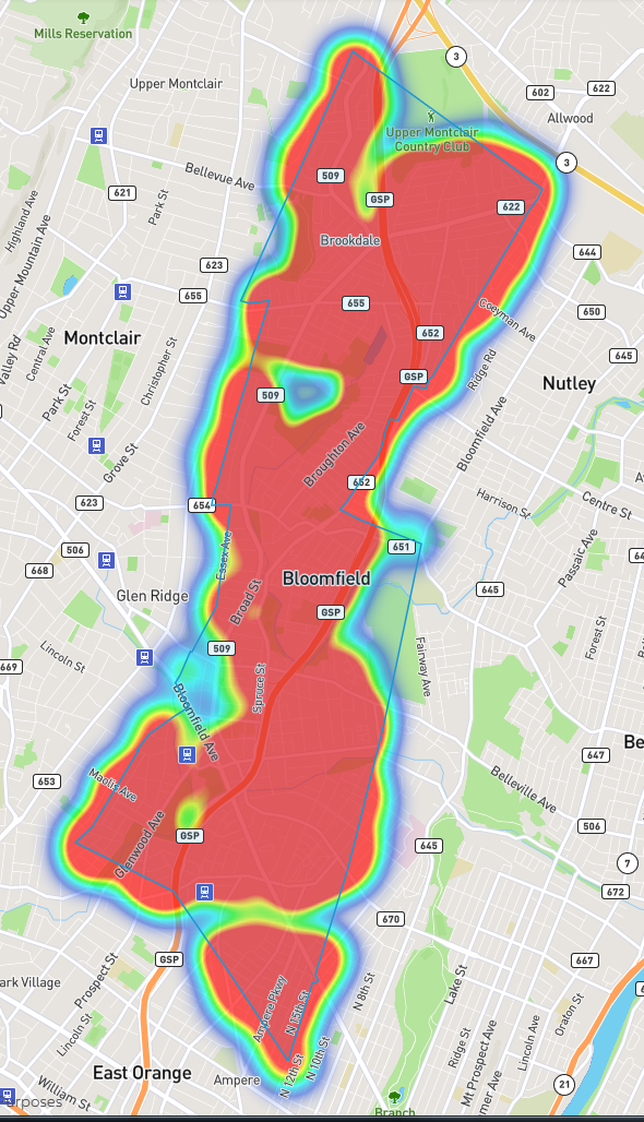

The sheer number of cameras run by Amazon’s Ring business is astounding. Here is a heat map of Bloomfield, New Jersey provided by the Bloomfield Police Department:

Ring cameras are everywhere.The closer it is to red, the more cameras there are.

There are hardly any spots in that New Jersey town that are out of sight of a Ring camera. The smart doorbells were already popular within the community, according to the police, so it made sense to partner with Ring for the law enforcement dashboard. Now, on top of those cameras being on seemingly every block, police could request footage from residents just from a tap on a phone.

When police partner with Ring, they have access to a law enforcement dashboard, where they can geofence areas and request footage filmed at specific times. Law enforcement can only get footage from the app if residents choose to send it. Otherwise, police need to subpoena Ring.

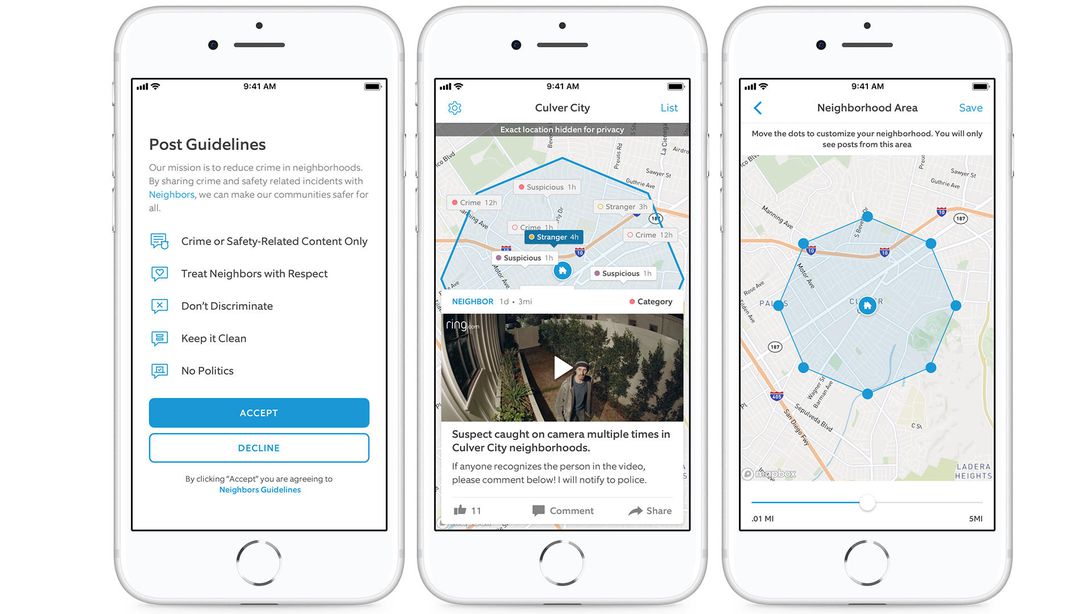

Police said the app has helped them solve crimes since residents usually send in footage of thieves on their steps stealing packages, or a suspicious car driving through the neighborhood. And the “Neighbors app” allows people to post videos and crime alerts. Police can request Ring footage through this app. The app looks like this (provided by the Ladera Heights, CA police department):

In almost all of these communities the residents say they feel more secure because the program offers a direct line to police. It’s about their safety and their property, not privacy. It’s a trade-off. They are probably perfectly fine with police being able to look at the street view outside their house.

Plus … it’s cheap. Generally, most people don’t have big-time surveillance systems in their home. But something simple like Ring, where you just plug it in? For $139 (full price) or $35 (when subsidised)? People will go for that. And police departments can cheaply piggyback on Ring’s network to build out their surveillance networks.

Figures are difficult to confirm but a representative of the National Police Association (a coalition of police unions and associations from across the United States organized for the purpose of advancing the interests of law enforcement officers through legislative advocacy, political action and education) estimates over 5,000 communities are in a Ring program.

To privacy advocates … well, a different story. Dave Maass, a senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, was quoted in several sources I read. His overview:

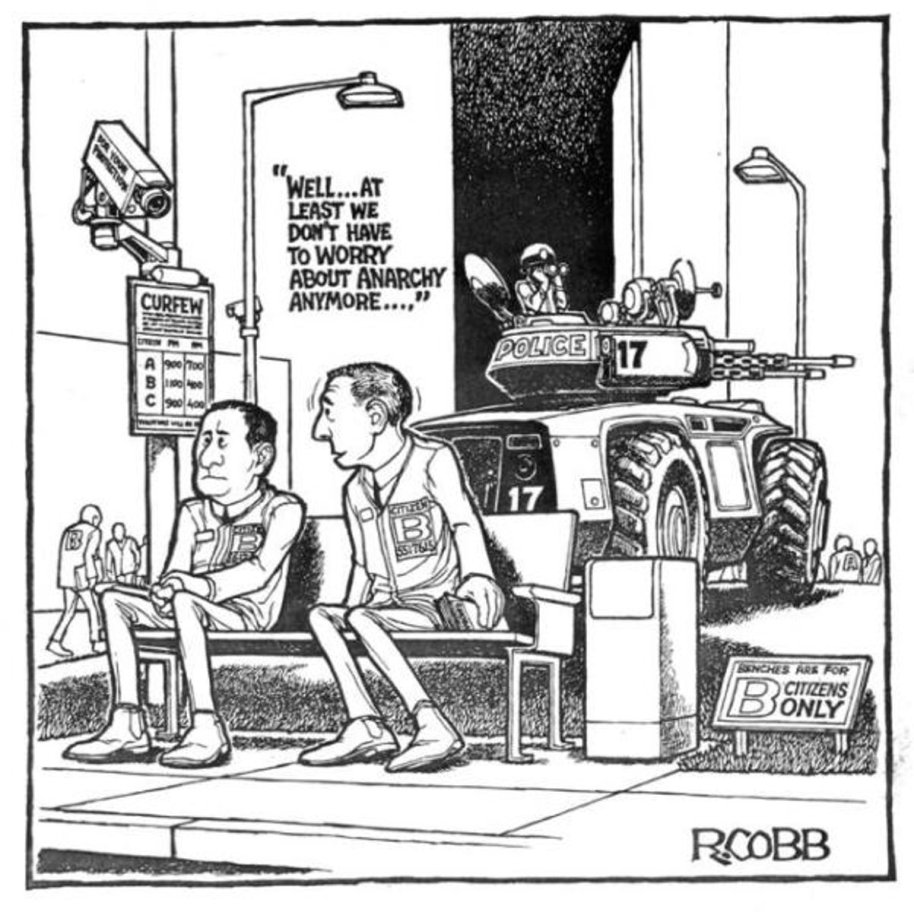

Essentially, we’re creating a culture where everybody is the nosy neighbor looking out the window with their binoculars. It is creating this giant pool of data that allows the government to analyze our every move, whether or not a crime is being committed.

And in a separate article, Maass explained the politics:

Look, think about it. Ring helps police avoid the roadblocks for getting surveillance technology, whether it’s due to a lack of funding or the public’s concerns about privacy. If the police department had to go and create a plan of where it was going to put all the cameras in the neighborhood, how much it was going to cost, and take it to the city council, maybe there would be some debate. There’s a reason we push for ordinances that require police department seek city council approval before they acquire any surveillance technology. Multiple cities have laws requiring a public process to debate how police use and buy surveillance technology. Community activists fight back against tools like facial recognition and automated license plate readers.

But here, it’s privatized. Everybody in the neighborhood has a device and they are inviting the police in. This essentially circumvents the whole process … while saving the city money. Part of the problem is that the public is financially subsidizing invasions of their own privacy in their communities when they do this.

While police need to ask for permission to get footage, the giveaway program in Houston, Texas is becoming the model. It ensures that law enforcement would get any videos it needed. It’s written into the requirements that winners of the giveaway program (who get their Ring for free) and the ones who get a subsidized Ring agree to give the Houston police access to the cameras when it’s requested. So the police are basically commandeering people’s homes as surveillance outposts for law enforcement.

And Amazon is more than willing to help. In several cities, for every 20 people who sign up for the app, Ring donates one camera. It’s why some police departments have been pushing for more residents to sign up. Police promoting the cameras also helps Amazon’s profits. Even when Ring is giving the cameras away for free or providing subsidies, it quickly finds a return on its investment. You don’t have to have a Ring subscription, but it’s the only way you can store footage recorded from the camera. The cheapest plan starts at $3 a month. Even when Amazon donated $18,750 to one subsidy program, it could make all of that back in less than a year with 600 new subscriptions.

And the technology is evolving.

Ring isn’t limited to Amazon’s own technology, more tech-savvy police departments have found. While Ring faced backlash last December when it was considering facial recognition for the doorbell cameras, police are capable of using the footage provided by residents with their own algorithms. Depending on how the Ring camera is set up, it can capture motion on the streets, like cars passing by. One police department that uses automated license plate readers has developed a program that can use footage from Ring cameras to track down vehicles. Police can enter details on a car captured in Ring footage, search in the license plate reader system, and figure out the car’s owner and address.

That’s something unheard of. With Ring now picking up any motion in vehicles, maybe they won’t catch someone ringing the doorbell, but if it drives by, Ring turns on and captures that vehicle.

And as policing becomes more technology-driven, perhaps we have a new issue: police acting in the interest of commercial enterprises. Huh. Maybe the President of the United States could put a stop to that.