As the GDPR turns one year old, a look at obfuscation, corporate trickery, and the enforcement blues

(Part 2 of a 4 Part series)

GDPR: the regulator’s view

GDPR: the corporate view

-

There continues to be a legal “war zone” as obfuscation and corporate trickery ramps up. In part 1 of this series I addressed just one example: the manipulation and abuse of Data Privacy and Data Subject Access Requests. That post generated 322 responses (“Oh, yeah, agreed! Here’s what I went through to get MY data!!) which I will summarise in the last part of this series.

-

The recently announced “probe” of Google by Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner (which is the subject of this part of my series) will show how ad giants and others handle personal data across the internet, and the immense complexity of showing where that data goes.

-

But what the GDPR misses … and no single regulation can ever address … is how these platforms exercise quasi-sovereign powers across the many contexts we navigate. Data control is not the issue. That I will address in Parts 3 and 4 of this series.

28 May 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) – One of the things at which I marvel is how all the GDPR “experts” out there do not understand that data protection is just one piece of the puzzle, and the GDPR is the floor, not the ceiling. Without effective competition and application (big players can and will impose their terms and conditions on the treatment of data), without sectoral privacy laws (the EU’s yet-to-be-finalized ePrivacy Regulation being just one example, and one more important than the GDPR), things will fall through the cracks. Also, add in a consumer protection level.

And to be fair, the GDPR’s real strength (if it has any) will be in its enforcement. Although that can be said about any law. A year is simply too early to judge how exactly GDPR will be enforced in all areas that are being contested. But this insistence on monetary fines to “solve” the data privacy issues is so, so misplaced (to be covered in detail in Parts 3 and 4 of this series).

The biggest, most underrated components of the GDPR? Two: (1) handling automated decisions and (2) data portability. I will say in its defense(!) the GDPR is ahead of its time on both points, and few are paying attention to them. But the complexity of the GDPR’s attempt to “interpose humanity into ML-based choices” (quote from one of the GDPR-data-tracking-mavens I work with at Privacy International) and to know and track this data to create a framework for personal data ownership and control is a daunting task.

For just a taste, here is a clip from the BBC show “Click” which broadcast last week, the show entitled GDPR: One Year On. It was hosted by Carl Miller, and some of the interviews were conducted at Imperial College in London (a source for much of my own knowledge on data tracking). It is a piece on the amount of data devices collect about you, the incredible distribution of that data to multiple companies (the number and scope unknown), the business models employed by companies, how these companies create “data doppelgängers” of who they think you are … and the total lack of transparency in almost all of this. For those of you in the UK, the show will be rebroadcast this Saturday, June 1st. And if you have access to BBC iPlayer it will be on-site for awhile.

[ if reading this on your mobile device, the video may not automatically pop up; you may need to click on the Twitter link highlighted below]

— Carl Miller (@carljackmiller) May 27, 2019

NOTE: I have met Carl and I have quoted him numerous times in past posts. He has dived into the murkiest depths of the net in his first book, The Death of the Gods; The New Global Power Grab (the Gods in question being the structures and institutions that have governed and shaped our world for living memory, even centuries) and he does a marvellous job detailing Big Tech trend towards monopoly (unimpeded), and the rise (and power) of the algorithm-powered data scientist.

And there is a lot of personal data streaming out there. Let’s take a look at the Ireland/Google case.

Data, data, data … streaming everywhere!

Google: subject of the first GDPR probe by Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner

So … the first major standoff between Google and its lead privacy regulator in Europe, raising the many difficult questions about how the ad giant handles personal data across the internet. It will be an interesting look at how Google treats personal data at each stage of its ad-tracking system.

And, yes, there were a few raised eyebrows. Ok, a lot of raised eyebrows. As I wrote in previous posts, the GDPR, the product of years of wrangling with data companies, became vulnerable of one key provision on which the tech companies prevailed: that the lead regulator be in the country in which the tech firms have their “data controller” – in most cases, Ireland. So that companies were not subject to 28 regulators. Ireland’s willingness to crack down on the companies that dominate its economy has long been questionable, not least of which is the fact the current Data Protection Commissioner, Helen Dixon, came straight out of Ireland’s Department of Trade, obviously heavily pro business. And as we learned from a recently released trove of Facebook emails, Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, heavily lobbied for her to be appointed.

Because as I have written before, in Ireland it is the appearance of an investigation rather than the substance of one that counts. Ireland continues to take a more corporate-friendly approach to regulation than many of its EU counterparts, openly favoring negotiation over sanctions and lists of questions over on-site inspections. Those last two powerful tools … sanctions and on-site inspections … are never authorized but used by all other national data protection offices.

Which will make this new Google probe — interesting.

There are three different parts to your data-self:

1. The small amount of data you actually volunteer

2. The data generated when you use a service or device (see the BBC show above)

3. And the far most interesting: data that has itself been created from other data that had been collected

It’s this last bit of data that is the “Holy Grail” for Big Tech and advertisers because it provides the juice for the “behaviorally” targeted advert. The ecosystem to create this data is a relatively recent development in online media. Only as recently as December 2010 did a consortium of advertising technology (“AdTech”) companies agree the methodology for this approach to tracking and advertising.

And despite the grace period leading up to the GDPR, the AdTech industry has built no adequate controls to enforce data protection among the many companies that receive data. I will explain this in much more detail in Parts 3 and 4 but a few points vis-a-vis the Google case.

The Google ad system (similar to the others) is automatic, and incredibly fast. Every time a “behaviorally” targeted advert is selected to be served to a person visiting a website, the system that pre-selects that advert (the system is known as “Real-time bidding”, or sometimes referred to as “programmatic which simply means automatic) sends it out for a bid to hundreds or thousands of companies to get their $$$ to stick it on the website, and your personal data goes out to all those companies.

What kind of data is collected and disseminate in Google’s case? Ok, stand back …

● What you are reading or watching

● Your location

● Description of your device

● Your IP address (depending on the bidding system)

● Data broker segment ID, if available. This could denote things like your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc. (again, depending on the bidding system)

These data show what the person is watching and reading, and can include – or be matched with – data brokers’ segment IDs that categorise what kind of people they are. (How? You need to parse the bid requests and advertising protocols, which I did, but you’ll need to hang on until Parts 3 and 4 for the explanation).

And sometimes “data management platforms” (of which Cambridge Analytica is a notorious example) can perform a “sync” that uses this personal data to contribute to their existing profiles of the person. They aren’t placing an ad, or want to use an ad. But they want the data to improve their profiles. But that “sync” is not possible without the initial bid request so they join the solicitation bid just to get the data.

And therein lies the magic. Unique tracking IDs or “cookie matches” are created to allow advertising technology companies to try to identify you the next time you are seen, so that a long-term profile can be built or consolidated with offline data about you – your “data doppelgänger”.

The GDPR issue

The overriding commercial incentive for many ad tech companies is to share as much data with as many partners as possible, and to share it with partner or parent companies that run data brokerages. Clearly, releasing personal data into such an environment has high risk.

And let’s ignore Google’s press release with the statement “We welcome the opportunity for further clarification of Europe’s data protection rules for real-time bidding. Authorized buyers using our systems are subject to stringent policies and standards.”

Because despite this high risk, the systems establish no control over what happens to these data. Even if a bid request traffic is secure, there are no technical measures that prevent the recipient of a bid request from, for example, combining them with other data to create a profile, or from selling the data on. In other words, there is no data protection.

Their own protocols and documentation … there is a doozy entitled “GDPR Transparency & Consent Framework” … say that a company that receives personal data should only share these data with other companies if “the Vendor has a legal basis for processing the personal data”. In other words, the industry is adopting a “trust everyone” approach to the protection of very intimate a justified basis for relying on that data once they are broadcast.

There are no technical measures in place to adequately protect the data. My advertising sources tell me the industry is developing a tool in collaboration with a vendor that creates GDPR “consent management platforms” (CMPs). But one of my closest data wrangler colleagues in the ad biz told me the CMP code he saw and the technical specifications and protocols would still have no way of knowing whether, for example, a company had set up a continuous server-to-server operation to transfer that personal data to other companies.

This is particularly egregious since the data concerned are very likely to be “special categories” of personal data. The personal data in question reveal what a person is watching online, and often reveal specific location. These alone would reveal a person’s sexual orientation, religious belief, political leaning, or ethnicity. In addition, a “segment ID” that denotes what category of person a data broker or other long-term profiler has discovered a person fits in to.

Let’s close it off there and save some ammunition for the rest of the series.

Coming in Part 3 and 4: “data control” is not the issue. Nor is “explanation”.

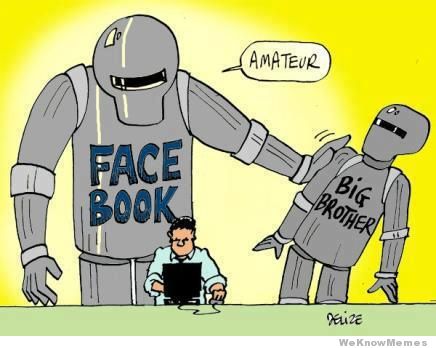

And the GDPR has inadvertently given even MORE power to Facebook, Google et al.

Everyone emphasizes “control” of personal data as core to privacy. The need for data minimization. It has certainly been seized upon by the “Privacy by Design” crowd.

But control is the wrong goal for privacy by design, and perhaps the wrong goal for data protection in general. Too much zeal for control dilutes efforts to design information tech correctly. This idealized idea of control is impossible. Control is illusory. It’s a shell game. It’s mediated and engineered to produce a particular control. If you are going to focus on anything, design is everything. The essence of design is to nudge us into choices. Asking companies to engineer user control incentivizes self-dealing at the margins. Even when good intentioned, companies ultimately act in their own self interests.

Even if there were some kind of perfected control interface, there is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships?

And GDPR conflates explanation and transparency. Explanation is distinct from transparency. Explanation does not require knowing the flow of bits through an AI system, no more than explanation from humans requires knowing the flow of signals through neurons (neither of which would be interpretable to a human anyway). Instead, explanation, as required under the law is about answering how certain factors were used to come to the outcome in a specific situation. The regulation around explanation from AI systems should consider the explanation system as distinct from the AI system.

And when you look at the advertising industry … specifically AdTech which has more to consider vis-a-vis the GDPR … and you look at the issue of opacity in machine learning algorithms, and mechanisms of classification and ranking, and spam filters … oh, hell, all these mechanisms of classification for the personal and trace data we generate every day is critical in our network-connected, advanced capitalist societies, for the benefit of Big Tech. That’s why you see:

– how the GDPR will fail at the very things it was meant to solve.

– that opacity is at the very heart of the concerns about “algorithms” among legal scholars and social scientists, and their complexity in operating on our data us not easy to grasp.

– why all those Big Tech attorneys and lobbyists moved the conversation away from algorithms and the “right to explanation” to issues about data control. And will continue to do so.

In Parts 3 and 4 I will get further into the weeds.