The pivots to encryption, Facebook’s move away from the newsfeed, and the platforms’ calls for more “privacy” and “more social media regulation”. Social media’s judo moves. Brilliant.

But the major problems and complexities of the three major social media platform technologies will defy regulation.

Herein, Part 1 of a 4-part series.

17 May 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) – Technology is just another human creation, like God or religion or government or sports or money. It’s not perfect, and it never will be. In many respects, it is a miracle. And the tectonic shifts in our relationship with technology go way beyond social media.

Opening salvos

When I look at the trillions of dollars … trillions! … by any number you like (sum of the market cap of the major tech companies, or Apple’s valuation on a good day, or the measure the number of dollars pumped into the economy by digital productivity, or the possible future earnings of Amazon, or whatever) I think “Jesus, this is what Commodore Amigas and AOL chat rooms and Pac-Man machines and Neuromancer got us to?!”

I grew up in an age of penmanship and copybooks, shelves of hardbound books and Dick and Jane readers, and blue mimeographs. Today, we are all children of Moore’s law. Everyone living has spent the majority of their existence in the shadow of automated computation. In my pocket I have a piece of green plastic with billions of transistors, soldered by robots, encased in glass … called a phone. A technology that is to the rotary phone what humans are to amoebas. But all of it has created what Paul Ford (uber programmer, award–winning essayist on technology) in his upcoming book calls a microscopic Kowloon Walled City of absolutely terrifying technology.

Facebook (to use my primary example) started out with one simple, noble mission: to psychologically atomize the global population for our own economic benefit, all while doubling down on the Orwellian claim that we’re “bringing people together”. Well, that was the plan. Then Mark figured “Gee, I could make billions of dollars from this!” Well, ok, maybe that was in the original plan, too.

We created a new existential malaise (latest Pew study: doctors have found that feelings of loneliness and isolation are particularly widespread among Americans who came of age during the rise of Facebook). But, boy, it sure beats the empty materialism of the eighties! And the depressed listlessness of the nineties! Doesn’t it?

Yes, many people – smart, kind, thoughtful people – thought that comment boards and open discussion would heal us, would make sexism and racism negligible and tear down walls of class. We were certain that more communication would make everything better. Arrogantly, we ignored history and learned a lesson that has been in the curriculum since the Tower of Babel, or rather, we made everyone else learn it. We thought we were amplifying individuals in all their wonder and forgot about the cruelty, or at least assumed that good product design could wash that away.

It wasn’t to be. We watched the ideologies of an industry collapse. Autocracy kept rearing its many heads. At its worst, people started getting killed, and online campaigns of sexual harassment against women was uncontrollable. We forgot our history. The arc of the moral universe does not bend toward moral progress and justice. Freedom, democracy, liberalism are mere blips on the screen of humanity. Autocracy, totalitarianism and dictatorships have long ruled the roost. And for those tech nerds among us, we made that constant mistake of correlating advancements in technology with moral progress. We metastasized into an army of enraged bots and threats. That blip of nostalgia and cheer has long been forgotten.

And so the shouts “WE MUST FIX THIS!!”

Over the last two weeks … at the Facebook developer’s conference (called “F8”) and at the Google’s developer conference (called “I/O”) … we heard Mark Zuckerberg say “Privacy gives us the freedom to be ourselves” and Sundar Pichai, chief executive officer of Google, say “Our work on privacy and security is never done. The present is private”.

Yep. Facebook pivots to what it wishes it was, not what it is: the cluttered mess of features that seem to constantly leak user data. People waste their time viewing inane News Feed posts from “friends” they never talk to, enviously stalking through photos of peers or chowing on click-bait articles and viral videos in isolation. Facebook is desperate to shake off 12 years of massive privacy mistakes and malfeasance (I start with 2007, its first massive privacy mistake being “Beacon” which quietly relayed your off-site e-commerce and web activity to your friends). Facebook is too late here to receive the benefit of the doubt.

Google? As I have noted before, Google gets less privacy flak than Facebook despite collecting much more (and more intimate) data. My theory is that’s because Google takes people’s data but in exchange for useful things (maps, documents, email, etc.) while Facebook exchanges data for things that make them sad and angry and polarised and brutal … and feeling used.

There is a difference in strategy. For Facebook, privacy is a talking point meant to boost confidence in sharing, deter regulators and repair its battered image. For Google, privacy is functional, going hand-in-hand with on-device data processing to make features faster and more widely accessible.

And look, everyone wants tech to be more private, but let’s take a hard look and discern between promises and delivery. Like “mobile,” “on-demand,” “AI” and “blockchain” before it, “privacy” cannot be taken at face value.

So don’t for one second be fooled by Google’s marketing department. Doing better than Facebook does not equate to doing good. Google, like Facebook, makes money through surveillance capitalism. Irrespective of their supposedly privacy enlightenment, their financial incentive to accumulate user data remains intact. Unless this incentive is squashed, they will never give back the power to us.

So let’s call it exactly as it is:

- Truth #1: Facebook is a psychologically predatory, commercially unscrupulous advertising platform masquerading as a virtuous social-media network. Its only value comes from selling the personal data of a third of the global population. Yes, we volunteer this data. But therein lies the solution. We created Facebook for Zuckerberg. Collectively, we wield far more power than he does.

- Truth #2: let’s not assign Zuckerberg the unenviable job of sole moral governor for Facebook’s users. Let’s not perpetuate the trope that social-media users can abdicate personal responsibility for using their own judgment. If Facebook fails to take steps to prevent and anticipate malicious uses of its platform, shame on it. If we mindlessly submit to being the agent of anyone’s algorithm — benevolent or corrupt — shame on us.

Before we get to the nuts and bolts and nonsense of regulation, a wee bit of background and history:

Writing this series

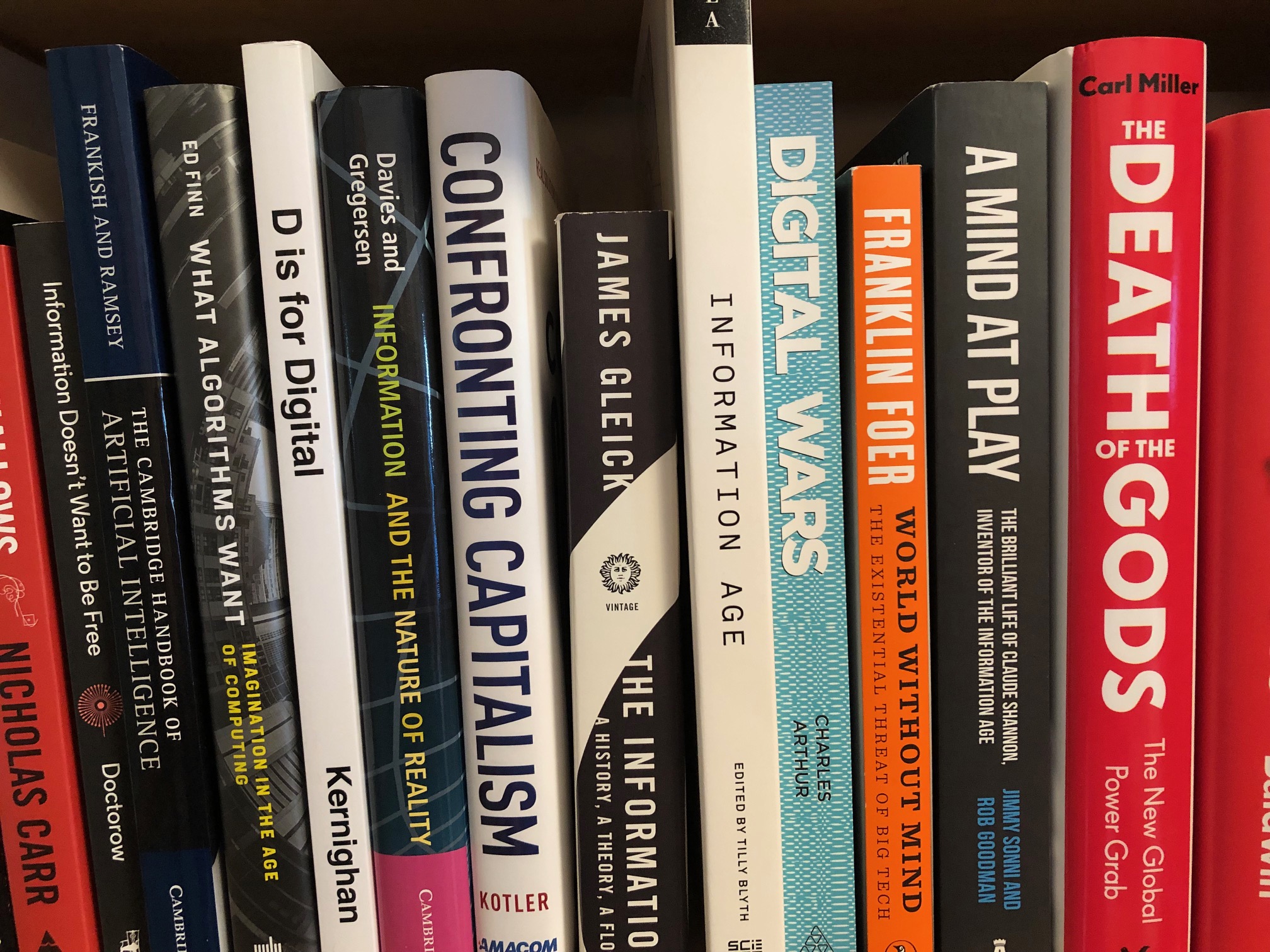

To be an informed citizen is a daunting task. To try and understand the digital technologies associated with Silicon Valley — social media platforms, big data, mobile technology and artificial intelligence that are increasingly dominating economic, political and social life – has been a monumental undertaking that brought me to interview scores of advertising mavens, data scientists, data engineers, social media techies, psychologists, etc. Plus reading reams of white papers and stacks of books tracking the evolving thinking and development of these technologies.

A few selections from my source material

I also needed to dust off some classic tomes that have sat in my library for years, from authors such as James Beniger, Marshall McLuhan, Neil Postman and Alvin Toffler … all of them so prescient to where technology would lead us, their predictions spot on to where we are today.

A few more selections from my source material

Even Hannah Arendt. In her book “The Human Condition” (published in 1958) she says the human condition that we suffer from is diminishing human agency and political freedom, and that’s due to a paradox: as human powers increase through technological and humanistic inquiry we become less equipped to control the consequences of our actions and that will continue into our future.

Because when you read Beniger, McLuhan, Postman and Toffler (my third ride through these tomes) this big “Information Society” we think is so new is not so much the result of any recent social change (information has always been key to every society) but due to the increases begun more than a century ago in the speed of material processing. Microprocessor and computer technologies, contrary to currently fashionable opinion, are not new forces only recently unleashed upon an unprepared society, but merely the latest installments in continuing development. It is the material effect of computational power that has put us in a tizzy.

Markets have always been predicated on the possession and exchange of information about goods and the condition of their availability. But what’s different this time is that with the introduction of digital technologies and the ubiquitous status they have attained, information has become the basic unit of the global economy.

But it was Neil Postman, the legendary public intellectual who had emerged as the earliest and most vocal scold of all that is revolutionary, that nailed it as far as the future Facebook. He had written the 1985 bestseller Amusing Ourselves to Death, about the ways that television had deadened our public discourse by sucking all modes of deliberation into a form defined by the limitations of entertainment. He would go on a decade later to raise concerns about our rush to wire every computer in the world together without concern for the side effects, and that we would enter an age where “social information connections would have negative implications with which we would grapple with the utmost difficulty”.

Many of my readers know these books. I am a Baby Boomer (age 68) so I rode the optimistic waves of the post–Cold War 1990s. The U.S. was ascendant in the world, leading with its values of freedom, ingenuity, and grit. Crime was ebbing. Employment was booming. I was a fellow traveler in a movement that seemed to promise the full democratization of the Enlightenment. Digital technology really seemed to offer a solution to the scarcity of knowledge and the barriers to entry for expression that had held so much of the world under tarps of tyranny and ignorance. I remember those old computers, some of those early “laptops”. If you ran those things for too long it would get hot enough to double as a toaster.

But in the end we became governed by an ideology that sees computer code as the universal solvent for all human problems. It is an indictment of how social media has fostered the deterioration of democratic and intellectual culture around the world. We hear that technological evolution has affected every generation, that it always affects behavior and lifestyle. We read comparisons of all aspects of the digital revolution to be “obviously similar” to that of the Gutenberg Press.

Wrong. These analogies are so far off the mark. When we cannot explain something, we revert to something we do know. And so these overwrought and misused historical analogies substitute for logic.

This time it is different. What is happening is an epochal shift that I equate to the discovery of fire and the invention of electricity.

A short (brutal) history of Facebook, social media in general, and Silicon Valley

The story of Facebook has been told well and often. But it deserves a deep and critical analysis at this crucial moment. Somehow Facebook devolved from an innocent social site hacked together by Harvard students into a force that, while it may make peronal life just a little more pleasurable, makes democracy a lot more challenging. It’s a story of the hubris of good intentions, a missionary spirit, and that ideology I noted above – computer code as the universal solvent for all human problems. And it’s an indictment of how social media has fostered the deterioration of democratic and intellectual culture around the world.

I had begun to focus on all of this back in 2015 when I wrote a short essay on the new “public square”: how data, code and algorithms were driving our civil discourse. And then … the apocalypse. I wrote:

We no longer share one physical, common square, but instead we struggle to comprehend a world comprised of a billion “Truman shows”.

So just how in hell how did one of the greatest Silicon Valley success stories (Facebook) end up hosting radical, nationalist, anti-Enlightenment movements that revolt against civic institutions and cosmopolitans? How did such an “enlightened” firm become complicit in the rise of nationalists such as Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Narendra Modi, Rodrigo Duterte … and ISIS? How did the mission go so wrong? Facebook is the paradigmatic distillation of the Silicon Valley ideology. No company better represents the dream of a fully connected planet “sharing” words, ideas, images, and plans. No company has better leveraged those ideas into wealth and influence. No company has contributed more to the paradoxical collapse of basic tenets of deliberation and democracy.

The past decade has been an exercise in dystopian comeuppance to the utopian discourse of the ’90s and ‘00s. It is a never-ending string of disasters: Gamergate, the Internet Research Agency, fake news, the internet-fueled rise of the so-called alt-right, Pizzagate, QAnon, Facebook’s role in fanning the flames of genocide, Cambridge Analytica, and so much more. I spoke to techies at Facebook and Google and Twitter and got a similar response. A composite answer to interviews I conduced:

In many ways, I think the malaise is a bit about us being let down by something that many of us really truly believed in. Quite frankly, I have many friends and colleagues who were more realistic about tech and foresaw its misuse, but nobody listened. The rest of us? Just stunned by the extent of the problem. You have to come to terms with the fact that not only were you wrong, but you were even complicit in how this all developed.

Silicon Valley grew out of a widespread cultural commitment to data-driven decision-making and logical thinking. Its culture is explicitly cosmopolitan and tolerant of difference and dissent. Both its market orientation and its labor force are global. Silicon Valley also indulges a strong missionary bent, one that preaches the power of connectivity and the spread of knowledge to empower people to change their lives for the better.

Facebook’s leaders, and Silicon Valley leaders in general, have invited the untenable condition by believing too firmly in their own omnipotence and benevolence. These leaders’ absolute belief in their sincerity and capabilities, combined with blind faith in the power of people to share and discuss the best and most useful information about the world, has driven some terrible design decisions. We cannot expect these leaders to address the problems within their own product designs until they abandon such faith and confidence in their own competence and rectitude.

The dominance of Facebook and Youtube on our screens, in our lives, and over our minds has many dangerous aspects. This has been the subject of countless books, blog posts, magazine articles, and video interviews of social media pundits. But there are technological aspects rarely discussed although some have done a deep dive into these technological aspects such as Anand Giridharadas in his book Winners Take All, Siva Vaidhyanathan in his book Antisocial Media, and the Oxford University Internet Institute which has published a series of detailed monographs.

I read all of those sources and offer the following mash-up of their principal points:

1. The first is the way in which false or misleading information can so easily spread through Facebook and not be countered when proven false. We’ve seen this in post-election stories about the flurry of “fake news”, which is actually just one form of information pollution. As the saying goes “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on”.

NOTE: that quote is commonly attributed to Mark Twain, but according to a researcher Gary O’Toole, it appears nowhere in Twain’s works. O’Toole did a lengthy analysis of the quote and he believes it is a descendant of a line published centuries ago by the satirist Jonathan Swift: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it; so that when Men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the Jest is over, and the Tale has had its Effects”. Variants emerged and mutated over time until the modern version quoted above – the “Mark Twain” version – became the standard.

2. Types of content in the Facebook News Feed are often visually indistinguishable, especially as we rush through our feed on a small screen. Items from YouTube to the Washington Post to ads from stores all come across with the same frames, using the same fonts, in the same format. It’s not easy for users to distinguish among sources or forms of content.

3. It’s also impossible to tell an opinion piece written for one of the dozens of blogs the Washington Post and other mainstream media outlets host, from a serious investigative new story that might have run on the front page of a newspaper. The aftermath of the 2016 election was consumed by analysis and reports about how easily images and text carried absurd lies about the major candidates that echoed around Facebook.

4. And that’s largely because Facebook has none of the cues that ordinarily allow us to identify and assess the source of a story. It’s not just a demand-side problem, though. Those who wish to propel propaganda to echo through Facebook long ago cracked the code.

5. There is also a big structural problem regarding Facebook. It amplifies content that hits strong emotional registers, whether joy or indignation. Among the things that move fast and far on Facebook: cut puppies, cute babies, clever listicles, lifestyle quizzes … and hate speech. Facebook is explicitly engineered to promote items that generate strong reactions. If you want to pollute Facebook with nonsense to distract or propaganda to motivate, it’s far too easy.

6. But that structural problem applies to all of social media, like Twitter’s “trending topics” and Google’s “news focus”. The algorithms choose the most extreme, polarizing message and image. Extremism will generate both positive and negative reactions, or “engagements”. Facebook measures engagement by the number of clicks, “likes”, shares, and comments. This design feature – or flaw, if you care about the quality of knowledge and debate – ensures that the most inflammatory material will travel the farthest and the fastest.

7. And all these authors make a similar comment: sober, measured accounts of the world have no chance on Facebook. And that is important because when Facebook dominates our sense of the world and our social circles, we all potentially become carriers of extremist nonsense. OpenDemocracy noted in a January 2019 survey of people in the “19-to-29” age group, 67% use the Facebook News Feed as their sole source of news. And because reading the News Feed of our friends is increasingly the way we learn about the world and its issues, we are less likely to encounter information that comes from outside our group, and thus are unaware of countervailing arguments and claims.

A battle we have lost

The structure and function of Facebook work powerfully in the service of motivation. If you want to summon people to a cause, solicit donations, urge people to vote for a candidate, or sell a product, few media technologies would serve you better than Facebook does. Facebook is great for motivation. It is terrible for deliberation. Democratic republics need both motivation and deliberation. They need engaged citizens to coordinate their knowledge, messages, and action. They need countervailing forces to be able to compete for attention and support within the public sphere. But when conflict emerges, a healthy democratic republic needs forums through which those who differ can argue, negotiate, and persuade with a base of common facts, agreed-upon conditions, clearly defined problems, are an array of responses or solutions from which to choose.

But there is a development making this impossible: people’s “dueling facts” are driven by values instead of knowledge. The Mueller report is one of the best examples of this. That report was supposed to settle, once and for all, the controversy over whether the Trump team colluded with Russians or obstructed justice. Clearly, it has not. Reactions to the report have ranged from “Total exoneration!” to “Impeach now!”

Surely nearly 700 hundred pages of details, after almost two years of waiting, helped the nation to achieve a consensus over what happened? Well, no. As Goethe said in the early 1800s, “Each sees what is present in their heart.”

Many have been studying the “dueling facts” issue in social media – long before Donald Trump was even a candidate – which is the tendency for Red and Blue America to perceive reality in starkly different ways. Based on that work, the fact that the Mueller report settled nothing is no surprise. The conflicting factual assertions that have emerged since the report’s release highlight just how easy it is for citizens to believe what they want — regardless of what Robert Mueller, William Barr or anyone else has to say about it.

What has happened to political discourse in the U.S.? Dueling fact perceptions became are rampant, and we began to see they were more entrenched than most people realized. Some examples of this include conflicting perceptions about the existence of climate change, the strength of the economy, the consequences of racism, the origins of sexual orientation, the utility of minimum wage increases or gun control, the crime rate and the safety of vaccines.

So can a community decide the direction they should go if they can’t agree on where they are? Can people holding dueling facts be brought into some semblance of consensus? Short answer? No. Because what is happening is that the “dueling facts phenomenon” is now primarily tribal, driven by cheerleading on each side for their partisan “teams.” People are reinforcing their “values” and their “identities” – irrespective of the “facts”. It is not the amount or type of media that one consumes. It is what we prioritize. We see this in the opinion polls: those who declare themselves Democrats favor compassion as a public virtue, which is relative to those who identify as Republicans and favor rugged individualism. Values not only shape what people see, but they also structure what people look for in the first place:

– Those who care about oppression look for oppression. So they find it.

– Those who care about security look for threats to it. And they find them.

In other words, people do not end up with the same answers because they do not begin with the same questions.

None of this happened by accident

Facebook’s dominance is not an accident of history. And I will examine this in more detail in the subsequent parts of this series. But in brief:

The company’s strategy was to beat every competitor in plain view, and regulators and the government tacitly – and at times explicitly – approved. In one of the government’s few attempts to rein in the company, the F.T.C. in 2011 issued a consent decree that Facebook not share any private information beyond what users already agreed to.

Facebook largely ignored the decree. Last month, the day after the company predicted in an earnings call that it would need to pay up to $5 billion as a penalty for its negligence – a slap on the wrist; regulators in the U.S. and Europe still think money fines are serious “penalties” – Facebook’s shares surged 7 percent, adding $30 billion to its value, six times the size of the fine.

The F.T.C.’s biggest mistake was to allow Facebook to acquire Instagram and WhatsApp. In 2012, the newer platforms were nipping at Facebook’s heels because they had been built for the smartphone, where Facebook was still struggling to gain traction. Mark responded by buying them, and the F.T.C. approved.

Neither Instagram nor WhatsApp had any meaningful revenue, but both were incredibly popular. The Instagram acquisition guaranteed Facebook would preserve its dominance in photo networking, and WhatsApp gave it a new entry into mobile real-time messaging. Now, the founders of Instagram and WhatsApp have left the company after clashing with Mark over his management of their platforms. But their former properties remain Facebook’s, driving much of its recent growth.

When it hasn’t acquired its way to dominance, Facebook has used its monopoly position to shut out competing companies or has copied their technology. It has spit on the laws regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies.

Thoughtessly thoughtless: why humans are so susceptible to fake news and misinformation

Those words are as true today as when Bertrand Russell wrote them in 1925. You might even argue that our predilection for fake news, conspiracy theories and common sense politics suggests we are less inclined to think than ever. Our mental lassitude is particularly shocking given that we pride ourselves on being Homo sapiens, the thinking ape. How did it come to this?

The truth is, we are simply doing what people have always done. The human brain has been honed by millions of years of evolution – and it is extraordinary. However, thinking is costly in terms of time and energy, so our ancestors evolved a whole range of cognitive shortcuts. These helped them survive and thrive in a hazardous world. The problem is that the modern milieu is very different. As a result, the ideas and ways of thinking that come to us most effortlessly can get us into a lot of trouble.

At this year’s International Journalism Festival, the Nieman Journalism Lab presented Julian Matthews (a research officer at the Cognitive Neurology Lab of Monash University) who studies the relationship between metacognition, consciousness, and related cognitive processes. He noted:

-Fake news often relies on misattribution – instances in which we can retrieve things from memory but can’t remember their source. Misattribution is one of the reasons advertising is so effective. We see a product and feel a pleasant sense of familiarity because we’ve encountered it before, but fail to remember that the source of the memory was an ad. One study examined headlines from fake news published during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The researchers found even a single presentation of a headline (such as “Donald Trump Sent His Own Plane to Transport 200 Stranded Marines,” based on claims shown to be false) was enough to increase belief in its content. This effect persisted for at least a week, and it was still found when headlines were accompanied by a fact-check warning or even when participants suspected it might be false.

-Repeated exposure can increase the sense that misinformation is true. Repetition creates the perception of group consensus that can result in collective misremembering, a phenomenon called the “Mandela Effect”: a common misconception and misquoted line that perpetuates itself deep within our culture.

Donald Trump uses it to its max: just keeping repeating repeating repeating the same false thing and it will eventually solidify and become “true”. As I have noted before, the mass rallies that Trump has made normal acknowledge no distinction between national politics and reality TV. He coaxes, he cajoles and he comforts his audience.

Oh, and it can also be in harmless stuff, too. We collectively misremember something fun, such as in the Disney cartoon “Snow White”. No, the Queen never says “Mirror, mirror on the wall …” She said “Magic Mirror on the wall …” But it has serious consequences when a false sense of group consensus contributes to rising outbreaks of measles.

At the core of all of this is bias. Bias is how our feelings and worldview affect the encoding and retrieval of memory. We might like to think of our memory as an archivist that carefully preserves events, but sometimes it’s more like a storyteller. Memories are shaped by our beliefs and can function to maintain a consistent narrative rather than an accurate record.

Our brains are wired to assume things we believe originated from a credible source. But are we more inclined to remember information that reinforces our beliefs? This is probably not the case. People who hold strong beliefs remember things that are relevant to their beliefs, but they remember opposing information too. This happens because people are motivated to defend their beliefs against opposing views.

One of the key points Matthews made was that “belief echoes” are a related phenomenon that highlight the difficulty of correcting misinformation. Fake news is often designed to be attention-grabbing. It can continue to shape people’s attitudes after it has been discredited because it produces a vivid emotional reaction and builds on our existing narratives. Corrections have a much smaller emotional impact, especially if they require policy details, so should be designed to satisfy a similar narrative urge to be effective.

So the way our memory works means it might be impossible to resist fake news completely. One approach suggested is to start “thinking like a scientist”: adopting a questioning attitude that is motivated by curiosity and being aware of personal bias, and adopting the following questions. But look at this list of questions and tell me … how many people are really going to do this?

1. What type of content is this? Many people rely on social media and aggregators as their main source of news. By reflecting on whether information is news, opinion, or even humor, this can help consolidate information more completely into memory.

2. Where is it published? Paying attention to where information is published is crucial for encoding the source of information into memory. If something is a big deal, a wide variety of sources will discuss it, so attending to this detail is important.

3. Who benefits? Reflecting on who benefits from you believing the content helps consolidate the source of that information into memory. It can also help us reflect on our own interests and whether our personal biases are at play.

A government regulator contemplates social media regulation

And so we move onto the hoary beast, government regulation of social media

Last week the French government announced plans to give regulators here sweeping power to audit and fine large social-media companies like Facebook if they do not adequately remove hateful content — an attempt to ratchet up global oversight of Silicon Valley. The French intend to create a “duty of care” for widely used social-media companies.

The French move accelerates efforts by governments from Berlin to Canberra to make tech companies more responsible for the inappropriate content their platforms sometimes distributes – whether it be electoral disinformation, terrorist propaganda or a pirated copy of a Hollywood film.

Tech lobbyists across the world have opposed efforts to create too many obligations to remove content, in part because they say it would hurt smaller firms without the resources to police every posting. And this is true. In March, the Information Technology Industry Council (a U.S. group) published a policy paper about all of the European tech proposals being floated to monitor or filter all content, opining that it will create “unrealistic or undesirable burdens.”

And Singapore approved a new law that requires social media platforms to take down or issue corrections to articles or statements posted on their platforms that the Singapore government “deem to be false.” And that’s the slippery slope, isn’t it? What if the statements are simply uncomfortable, but true? It would not be past any politician or government official anywhere in the world to “deem it to be false” in order to prevent more widespread understanding.

Meanwhile, what is happening in the real world? Let’s highlight a few things:

– A week after being banned by Facebook, Louis Farrakhan is … back on Facebook. A speech he gave at the Saint Sabina Catholic Church in Chicago (where he said he was “the most hated man in America today” and was a speech full of invective) was live streamed on the Saint Sabina Catholic Church Facebook account. Their Facebook account was not banned.

– Most of the Venezuelan government accounts are banned or restricted on Facebook and other social media. So the government turns to pro-regime Facebook accounts to publish information. There was phishing attack on a website run by Venezuelan opposition parties. The personal data of 100s of phishing victims was exposed across multiple social media venues, jeopardizing the victims’ safety.

– While religious extremist organizations may be small in number, in the online public space the use of links between sites within a network helps to create a collective identity. This forges a stronger sense of community and purpose, which can convince even the most ardent extremist that they are not alone and that their views are not, in fact, extreme at all. Media analysts have found that in their study of white supremacist sites, the alt-right and other right-wing extremist groups these groups have learned to use mutual links to create a collective identity and that these groups often use the same borrowed rhetoric of these religious extremist groups. And they have learned to use marketing and public relations (which is, let’s face it, a mix of facts, opinions, and emotional cues) to game the social media systems to make many of their pieces look “newsy” and escape scrutiny.

– And how bad are the “gatekeepers” in all of this? EXAMPLE ONE: This week Twitter suspended a Jewish newspaper in Germany because of a Tweet that contained a link to an interview in which the Israeli Ambassador says that he avoids all contact with the far-right AfD “because of the party’s dubious stance on the Holocaust”. Why? Because the Twitter algorithm (and the human reviewer) deemed it “election misinformation” and thus violated German laws aiming to combat agitation and fake news in social networks. Twitter admitted “we were mistaken” and restored the account. The fact that Twitter tolerates a tsunami of anti-Semitic hate Tweets but blocks messages from the only Jewish weekly newspaper in Germany – because of a Tweet that denounces the far right – is completely incomprehensible to me. But, hey – they say they can regulate this stuff.

– And how bad are the “gatekeepers” in all of this? EXAMPLE TWO: last weekend, in the UK, Nigel Farrage (head of the Brexit Party) was interviewed on the Andrew Marr program. It was an interview widely described as a “car crash”. Marr wiped the floor with him, showing him as the fraud he is. Yet a series of selected snippets of the footage (created for the Brexit Party) made their way across social media to bolster support for Farrage – all of his racism and misogyny and antisemitism and Islamophobia thoughts and his right conspiracy theories, clip-after-clip. Captioned “Marr gets eviscerated for repeatedly trying to smear Nigel” and using the BBC logos but cutting out Marr, it had more hits than the original BBC video of the full interview. It highlights the ways in which individuals harboring extreme views can effectively game the media and benefit from airtime, no matter how effectively the interviewer challenges them, and not get blocked by social media. In January, YouTube said it changed its algorithm “to stop recommending far-right conspiracy videos”. But the altered Marr/Farrage video went right to the top of the Youtube recommendation list.

– Alt-right organisations are setting up Linux servers in the cloud, sending out Tweets and Facebook posts with links to give people access, and people are setting up hundreds of web pages, all outside any monitoring or regulation. Hundreds of tiny pirate kingdoms.

Dearest, dearest regulator: how do you have the audacity, the impudence, the cheek to change or regulate an industry that will not stop, not even to catch its breath? A technology, an industry, an ecosystem you do not understand?

And no one loves tech for tech’s sake. All of this is about industry power — power over the way stories are told, the ability to do things on industry terms. The aesthetic of technology is an aesthetic of power – CPU speed, sure – but what do you think we’re talking about when we talk about “design”? That’s just a proxy for power; design is about control, about presenting the menu to others and saying, “These are the options you wanted. Trust me”. That is Apple’s secret: it commoditized the power of a computer and sold it as “design”. It’s the same way the industry emasculated the GDPR (Europe’s new General Data Protection Regulation) to make sure it did nothing do deter what it wanted, what it needed to function, steering the regulators to the “easy-to-deal-with” stuff that still allowed the regulators to feel they did something. (I will address the GDPR on Monday in a post not related to this series, in “celebration” of the GDPR’s first birthday).

In the remaining three parts to this series, I will address the nuts and bolts and futility of social media regulation. I will end this post with the three major problems of platform technologies and the implications of this in a global context:

1. Scale: there are 2.3 billion Facebook users, 1.6 billion WhatsApp users, 1.9 billion Youtube users, and 1.3 billion Wechat users. This is a global information economy like we have never seen before.

2. Algorithmic amplification. Platforms choose for us and amplify voices that enflame engagement, that generate strong emotional reactions and absurdity. Additionally, people choose to promote content as an expression of who they are or who they want to be, as a way of affiliating, rather than the fact-based what-is-true. You can train people to filter for themselves but that denies the toxicity of the ecosystem itself.

3. The advertising system. We are subject to mass surveillance by companies we are not allowed to understand and not allowed to challenge. Platform company profits are their sources of political power. They become ultimately invulnerable because of their wealth and crowd out so many other forms of expression.

The ecological problem that plagues these technologies is unfixable. And the how and why we speak of addressing these issues misses the complexity of the issue and impedes our ability to combat them. We use the language of “solution” and these platforms know there is no “solution” and regulators will tie themselves into knots. Use of the word “solution” implies that there is a single cause or a set of simple identifiable causes, not addressing the “long story” that this is about a very complex suite of technologies and processes. It buttresses the same fundamentalism that got us into this place to begin with.

And despite the companies’ best efforts to convince us otherwise, they play with our minds. Because we don’t need social media for all the things we’re told we need it for. We don’t need social media to make friends or build relationships. We don’t need it to become active or engaged in politics. We don’t need it to explore our cities or find new things to do. We don’t need it to hail a cab or catch a bus or fly on a plane. We don’t need it to hear new music or read new books. We don’t need it to do our shopping. We don’t need it to develop or discover subcultures or like-minded groups or to appreciate good design. We don’t need it to plan our lives. And we don’t need it to understand the world.

They have trapped out mindset. Instead of hoping that a regulatory breakup of a monopolistic platform like Facebook will usher in a new version of the same idea, we ought to use the opportunity to decide whether the idea itself is worth repeating. We will likely find that it is not — that the connections social media helps us make are often flimsy, that the perspective of the world we gain from using it is warped, and that the time we spend with it is better spent doing almost anything else. Very shortly, I will abandon social media although my media team will use it to distribute my blog posts. That will be the subject of another blog post.

But first, continuing next week, the remainder of this series: a deep dive into the economic, legal and cultural struggle to regulate and modify Big Tech.

2 Replies to “The many plans proposed to regulate social media are the equivalent of putting a band aid on a bullet wound. And just as futile.”