(with thanks to Catarina “Kat” Conti for invaluable contributions)

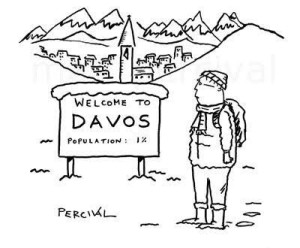

28 January 2018 – The World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting. Yes, “Davos Man” is lost in a blizzard of complexity – plutocrats and politicians who still rule the world have been given a shock this year over climate change and artificial intelligence. Samuel Huntington must be laughing in his grave. More than a decade ago the prescient political scientist popularized the term “Davos Man” in an 2004 essay. And he was not being complimentary. He coined the phrase to symbolize the “emerging global superclass.” His essay on this trope was titled “Dead Souls.” The rootless, denationalized elites, he argued, were out of touch with ordinary people’s yearning for tradition and community. It was this theme that Trump’s onetime strategist Stephen Bannon invoked when he said Trump’s enemies were “the party of Davos.” In Huntington’s vision, the people gathered were the problem, a condescending cabal that sought to impose its homogenizing will on the world.

Still, I will say that WEF is a tsunami of content and fascinating conversations that all seem interesting … but which often you are not part of. In past years I attended via a “purple badge” (the badge reserved for technicians who work behind the scenes) which was courtesy of a long-time media client. Now, after a looooong application process, I earned a media badge.

NOTE: The most coveted badge in all of Davos is one with a shiny holographic sticker on it — despite the fact that most attendees, and even some Forum employees, don’t actually know what the sticker actually means. It’s seen on the badge of every head of state, so some people thinks it means you are a head of state. It doesn’t. In fact, the shiny hologram grants you entry to the hyper-exclusive “Davos-within-Davos” known as IGWEL, or the Informal Gathering of World Economic Leaders.

To get in, you need to be a senior government policymaker — think finance minister, or trade minister, or one of their sherpas — or one of a very select group of WEF employees. And in fact the exclusivity does seem to help: if anything useful has ever been achieved at Davos, it has probably been achieved at IGWEL, which remains one of very few occasions where international politicians can meet informally, off the record, to talk about their biggest aspirations.

Oh, and just for fun, here is the cost to attendees for mingling with the swells at Davos:

- An annual membership to the World Economic Forum (required if you want to buy a ticket to Davos) costs $52,000. A ticket to Davos itself costs $19,000, plus tax (so that’s $71,000 for one person to come).

- If you want to go to the private industry sessions, which everyone here agrees are where the real value is, you have to become an “Industry Associate,” which costs $137,000 a year.

- If you want to bring a colleague, you can’t just buy another ticket for $19,000–you have upgrade your membership to “Industry Partner,” which costs $263,000 (vs $52,000). Then you have to buy the two tickets, for a total cost for 2 people of $301,000.

- If you want to bring a bunch of colleagues (max. 5 per company) you have to upgrade the membership to “Strategic Partner”, which costs $527,000. Then you have to buy the 5 tickets for $19,000 apiece. So bringing 5 people costs $622,000. And if you bring 5 people, you’re required to bring at least one woman, to make the meeting less of a sausage fest.

- And that’s just the cost of the conference. If you want to throw a party at Davos, which every self-respecting corporate attendee does, it will set you back at least $210 per guest. And you have to get here, which will cost $1,000 – $100,000 depending on what size plane you fly in and whether you want to drive from Zurich or fly in a helicopter ($3,400).

- And you have to stay here: the crappiest hotel rooms are $500 a night, and a private chalet costs $140,000 for the week.

So it’s no surprise that some companies spend “millions” on the Annual Meeting each year, as a senior executive at one big Davos sponsor told me.

“You will find me eager to help you, but slow to take any step”

Euripides, from “Hecuba”

And I am no fool. Only in passing, and probably on the margins of the official program (if even discussed) will they get into the tremendous monopoly and monopsony power of their companies, the ability to play one jurisdiction against another in order to avoid taxes, how to ban organized labor in their companies, how to use government ambulance services to carry workers who have fainted from extra heat (to save expense of air conditioning), how to make their workforce complement its wage through private charity donations, or perhaps how to pay the average tax rate between 0 and 12%. If they are from the emerging market economies they can also exchange experiences on how to delay payments of wages for several months while investing these funds at high interests rates, how to save on labor protection standards, or how to buy privatized companies for a song and then set up shell companies in the Caribbean or Channel Islands. Poverty and inequality which are, as we know, the defining issues of our time will hardly ever be permanently on their minds.

And this return to the industrial relations and tax policies of the early 19th century is bizarrely spearheaded by … IRONY ALERT!! … people who speak the language of equality, respect, participation, and transparency. Of course, none of them is in favor of a “Master and Servant Act” or forced labor. It just so happens that the language of equality has been harnessed in the pursuit of structurally most inegalitarian policies over the past fifty years, or more.

And the geopolitics …

Geopolitics is ever present. Last year, Donald Trump was a spectre haunting the WEF. This year … he was here! In the flesh! But he played to the crowd so, overall, it will not an uncomfortable encounter. Yes, yes, yes. He rejects the tenets of the liberal international order promoted by his country over seven decades. These values also animate the WEF. They are what make it something more than just a forum for the world’s rich and powerful. As Princeton’s John Ikenberry argues in a recent article that was floating around Davos this year, the “US and its partners built a multi-faceted and sprawling international order, organised around economic openness, multilateral institutions, security co-operation and democratic solidarity”. This system won the cold war. That victory, in turn, promoted a global shift towards democratic politics … and as Trump fully embraces, it also shifted to free-market economics.

Yep, Trump may represent the antithesis of everything the Davos crowd holds dear. But on the other hand, that crowd is making a lot of money these days. Common view: “It has been a very economically successful year. I didn’t expect it, but he’s been successful, and this must be celebrated.”

But let’s be frank. Trump and his cronies not only profit from, but *depend* upon, globalized kleptocracy. If you want to read more about the deep cynicism of Trump’s attacks on “globalists” just read Franklin Foer’s piece on Paul Manafort in the current issue of The Atlantic magazine (click here).

There was much talk about how the liberal international order is sick. As Freedom in the World 2018, published by Freedom House, a US state-funded non-profit organisation, states, “Democracy is in crisis”. For the 12th consecutive year, countries that suffered democratic setbacks outnumbered those that registered gains. States that a decade ago seemed promising success stories — such as Turkey and Hungary — are sliding into authoritarian rule. Yet now, when potent authoritarian regimes challenge democracy, the US has withdrawn its moral support. Trump even shows sympathy for autocrats abroad. Worse, argues Freedom House, he violates norms of democratic governance.

But my God is it a topsy-turvey world: Communist China is the world’s champion of free trade and globalization. The United States has turned its back on liberal values and is cozying up to Russia. And Europe, spurned by Washington and London, is turning to Beijing to fill the void. However, in this post I will not dwell on that, seeking to avoid a fall down the rabbit-hole of geopolitics spinning out of control. I prefer to chat about one topic that was a major discussion point this year: blockchain.

BLOCKCHAIN CHATTER AT DAVOS

World leaders and business bosses attended hundreds of talks, workshops, dinners, and other get-togethers. The takeaway: artificial intelligence and climate change are going to ruin us, but blockchain and women are going to save us.

While advances in AI are undoubtedly significant for humanity – Google CEO Sundar Pichai compared AI to the invention of fire – the potential for job losses and instability as industries adjust (or not), is tremendous. “At the end of the day, we have to fire a lot of people,” said Ursula Burns, chairman of the supervisory board at telecom group VEON. The angst of these losses could even lead to wars, warned Alibaba’s Jack Ma. Each technology revolution has made the world unbalanced, he said.

Meanwhile, tech giants like Facebook, feted as world-changing innovators last year, faced pointed criticism and calls for heavy regulation in areas like data privacy and fake news. Even tech executives – from Salesforce’s Marc Benioff to PayPal’s Dan Schulman – joined the chorus.

And then there are the truly existential threats, such as climate change and pandemics. When not talking about Trump’s intentions, Macron’s ambitions, or which party to go to, delegates were stunned into silence by scientists with apocalyptic environmental projections and frightening simulations of how outbreaks spread in our increasingly connected world.

On the plus side, it seemed that there was no problem too daunting that couldn’t be solved with blockchain technology. Multinational CEOs talked about how distributed ledgers could streamline supply chains and cut accounting costs. The younger, rowdier crowd at crypto-themed fringe venues that sprang up around Davos for the first time considered applications for mining space minerals and establishing no less than a “new base layer of our reality.” Although certainly fueled by cryptocurrency froth, the blockchain banter represented a genuinely novel topic of conversation that attracted fresh faces to an event where the same people often repeat their spiels about the same subjects year after year.

The talk at Davos was that the internet is entering a second era that’s based on blockchain. The last few decades brought us the internet of information. We are now witnessing the rise of the internet of value. Where the first era was sparked by a convergence of computing and communications technologies, this second era will be powered by a clever combination of cryptography, mathematics, software engineering and behavioural economics. Like the internet before it, the blockchain promises to upend business models and “disrupt industries” (ugg, that phrase again).

I cannot summarize in this post all the material I collected so let me close out this section with a few big themes gleaned from the several white papers WEF presented, including one by Ana Trbovich of Grid Singularity (and if you want to see a simply col, funky home page check out their web site by clicking here):

- Where the internet democratized information, the blockchain democratizes value and cuts to the core of legacy industries like banking. It also pertains to the management of money, wealth, intellectual property and other forms of value for which many societies expect government to protect the public interest.

- So we all need to acknowledge that, while governments and regulators alone lack the knowledge, resources and mandate to govern this technology effectively, government participation and even regulation will likely have a greater influence over blockchain technologies to ensure that we preserve both the rights and powers of consumers and citizens.

- People in free societies have the right to free speech and have the power to express it on the internet of information but not the power to protect it from piracy, hacking or censorship. One of the defining characteristics of an open permissionless blockchain is that no one has the right to anything. There are really just powers, what you have the power to do, what you can do. Joichi Ito, the Director of the MIT Medi Lab, put it in these terms: “You can regulate networks, you can regulate operations, but you can’t regulate software.” On the internet of value, people will have the power to express themselves and the power to preserve their expression without restriction.

- But … these differences don’t require government to control, oversee or somehow govern the blockchain revolution. The genius of distributed ledgers is that the technology (and everything that happens with it) is and must be distributed. Power is distributed. Heavy-handed government intervention would kill this embryonic technology in its egg.

- Rather, said numerous speakers, we need self-organizing, bottom-up and multistakeholder governance. In fact, this type of governance is the best protection from government interference and subjugation.

- According to Primavera De Filippi, faculty associate at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard and a permanent researcher at the National Center of Scientific Research in Paris, the absence of a formalized governance structure has two possible effects: either blockchain-based communities have dif culty acting … or reacting expeditiously or else informal and invisible power dynamics emerge, often more centralized than they appear.

- That bears repeating: without governance, invisible powers could emerge.

- And to conclude, there are three levels of blockchain that warrant stewardship:

- The first is the platform level, the protocols of blockchains such as bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple or Hyperledger. While people often speak of virtual currency as a financial instrument and blockchain as a payment system – and, therefore, relevant narrowly to banking and finance – we think of them more broadly as an ownership claim on a particular technology platform, a claim represented by a token that comes with decision rights and usually an incentive to ensure the platform’s long-term success.

- The second is the application level, the tools that run on platforms, tools such as smart contracts, that require massive cooperation between stakeholders to work. As with the internet, entrepreneurs have been quick to seize blockchain business opportunities and innovate business practices. The recent rise of so-called “initial coin offerings” is turbocharging growth at the application layer, raising regulatory questions and accelerating the need for multistakeholder governance. With the internet of information, various companies, governments, NGOs and individuals could simply build an application using either the web or more proprietary mobile platforms like the iPhone or Android. However, because blockchain is all about value, developers are building applications, networks and projects within particular ecosystems – sometimes with a complex assembly of stakeholders who create, exchange and manage value.

- The third is the overall ecosystem, the ledger of ledgers connecting (or not) bitcoin, Ethereum, Hyperledger, Ripple, Tendermint and other platforms. We found that many of these are quite different in their world views and choice of protocols but present a common set of issues that we think a variety of stakeholders – including consumers and citizens – should understand and be able to discuss.

I will have more on this topic in the coming weeks. I am working with the MIT Media Lab and with Jason R Baron and his inestimable team at Drinker Biddle to produce a video series on the various legal aspects of blockchain.

POSTSCRIPT

Amongst the AI programs there was an introductory discussion on how few of us understand the “architecture within which we live”. We have moved into an “internet singularity” where most of us are connected and living off a totally man-made system. Panelists discussed how that architecture is:

-

- algorithmically-driven

- subject to an almost uncontrollable connectivity, and

- now subject to an exponential growth in cyber threat avenues

As I have noted in my previous posts,no country has even come close to the U.S. in harnessing the power of computer networks to create and share knowledge, produce economic goods, intermesh private and government computing infrastructure, etc. — and so left the U.S. as the most vulnerable technology ecosystem to those who can steal, corrupt, harm, and destroy public and private assets, at a pace often found unfathomable.

The continuing issue which will be most difficult to overcome: the “capitalistic mindset” – get to the market quickly, in the least expensive fashion, building functionality first, security second.

The overriding fears of the panel: the barriers to technology are non-existent. Looking at the three “Horsemen of the Apocolypse” …

-

- IEDs (improvised explosive devices)

- drones

- cyber

…. anybody can build these, can do it, not just the nation-state anymore. We already know ISIS had built drones with IEDs, and intelligence officials have already discovered weaponized drones in Mexico.

And on a point mirrored in an earlier session, the intel community notes that most cyberterrorist attacks are not very sophisticated but they have been highly effective. And most have been committed by non-state actors targeting critical infrastructure systems. And obviously nation-state actors attempting to gain a tactical advantage by sabotaging military and critical infrastructure systems.