Lately I find myself unable to write anything that doesn’t sound like prayer, screaming or manifesto. Forgive me. Here is another one.

3 May 2025 — Today is World Press Freedom Day. It’s a moment when many international news outlets, alongside organizations such as the United Nations and Reporters without Borders, highlight the many and growing dangers to journalists around the world.

Last year was the deadliest for journalists in decades, with at least 124 reporters killed while doing their jobs, nearly 2/3 of them Palestinian reporters in Gaza – almost all of them directly targeted by Israel Defense Forces.

And beyond the threat of violence, journalists are facing extreme legal and economic threats from states and leaders who wish to silence them. Just this week, a Swedish reporter was sentenced in Turkey for “insulting” president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

I have been a journalist almost all of my life, my experience summarized at the end of this post. This is obviously an issue close to my heart.

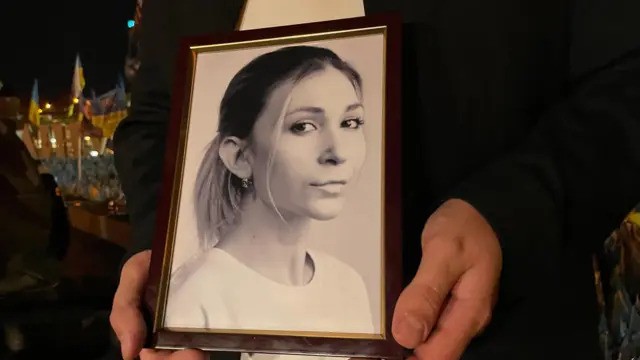

Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna was captured in 2023 and died after a year in Russian captivity, having set out to expose the systematic detention and torture of civilians in occupied Ukraine. She was in my Ukraine OSINT group and her reports were mortifying. Her capture and death inside Taganrog Sizo 2, a prison so notorious it has become known as Russia’s Guantanamo Bay, are even more mortifying.

The most drastic change since I marked this day in 2024 is the U.S. administration’s avowed hostility towards the press. The many lawsuits and intimidation tactics the administration is using against media groups is destroying the free press in America.

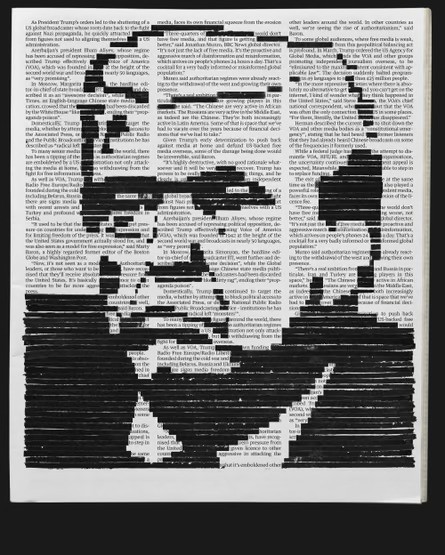

And Trump’s war on the press has had a huge international impact too. Russia and China are cheering Trump’s attacks on the media, especially as they have resulted in the dismantling of Voice of America – the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda – as well as the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas. As the UK newspaper The Guardian noted “it is a cocktail for a misinformed world”.

Intersecting with the physical dangers faced by many journalists around the world are a series of extremely challenging economic conditions facing media organizations.

Let’s unpack a few of these issues.

Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna fell victim to the very crimes she had set out to expose. Known to her family as Vika, Roshchyna grew up in the shadow of war. Her father was a veteran of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and she was 17 when Russia annexed Crimea. She and her sister were raised in the same town as Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Kryvyi Rih, where her parents still live, was 30 miles from the Russian advance into southern Ukraine in 2022.

Colleagues said she was obsessed with work and uncompromising. Sevhil Musaieva, the editor-in-chief of Ukrainska Pravda, summed up what many of Roshchyna’s colleagues said:

“She had no life beyond her job, no friends, no partner. But also doing extraordinary work. For her it was a mission. She was one of the bravest journalists I met in my career”.

To protect her sources, Roshchyna used multiple phones. She would set her messages to disappear, and her articles were written in files that would also self-delete. Roshchyna herself would vanish for weeks at a time, re-emerging to file her reports.

In March 2022, while reporting from the occupied city of Berdiansk, she had a first brush with danger. Captured by a soldier and turned over to agents of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), she was coerced into recording a propaganda video and let go a few days later, after a public outcry.

On her return home, colleagues urged her to rest and seek therapy. Her state of mind was fragile and she was very thin, they recalled.

But Roshchyna continued to cross the frontline. She exposed the intimidation of workers keeping the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station running, and investigated the shooting of two 16-year-old boys who had dared to oppose the occupation.

Musaieva said that on Roshchyna’s last journey she was looking for the location of black sites, basements or industrial buildings where Russian security operatives systematically used torture to interrogate civilians or coerce them into false confessions. She was building a list of the FSB agents responsible.

Through its enormous OSINT network, the Guardian was able to put together the story of her capture and death.

Roshchyna left Ukraine for the last time on 25 July 2023, taking a roundabout route into the occupied territories because there were no safe passages over the frontline. At 2.09pm that day, her phone connected to a Polish mobile network. From Poland, she travelled through Lithuania and north into Latvia.

A photo of her passport and her entrance form, obtained by the Guardian investigation, suggests she entered Russia from Latvia, under her own name, via the Ludonka border crossing. The card states she was heading to the city of Melitopol. She travelled 1,000 miles south through Russia, crossing into occupied Ukraine a few days later.

On the 3rd August, just a few days into her trip, her father, Volodymyr Roshchyn, raised the alarm after realizing she had stopped checking in to her online messaging accounts. Information he has gathered, together with the accounts of three people held with Roshchyna at a notorious prison in the Russian coastal town of Taganrog, just inside the Russian border, points to what happened next.

One of the witnesses was her cellmate, who was released last September and recorded her testimony on video for the prosecutor. She has asked not to be named, to protect herself and her family.

Roshchyna appears to have rented an apartment in Enerhodar, the dormitory town next to the Zaporizhzhia power plant. She paid in advance for three nights and, leaving her backpack behind, went out to search for black sites.

The journalist told her cellmate she thought she had been spotted by a drone. A police car arrived and she was taken to the police station, a five-story building covered in pockmarked blue tiles where the windows are reinforced with metal grilles. She was held there for several days before being moved 80 miles (130km) south to Melitopol. Said a European intelligence official familiar with the situation in the occupied territories:

“In Melitopol there is a big concentration of FSB and they have these temporary detention centres. In a process known as filtration, the FSB triages captives, depending on how valuable it deems them to be. Roshchyna is likely to have been considered a special case, given the information she was gathering”.

The intelligence officer believes she was taken to a black site in Melitopol known as the “garages”, and according to her cellmate’s testimony, Roshchyna later recounted how she was tortured there. Her body was covered in bruises:

“During interrogations, they used electric shocks. She got stabbed a few times – I saw them on her: arm for sure, legs, too. Fresh knife scar – forearm, soft tissue between wrist and elbow. A scar of roughly 3cm, pierced through. She said one guy, she called him a jerk. He was brutal, unhinged. On her leg, above the heel – I saw that too, 5cm wound. She said: ‘I told them not to touch my leg. I begged them not to touch that wound’. But they did anyway, she said”.

Towards the end of 2023, Roshchyna was told by an FSB officer she named as Maxim Moroz that she would be transferred to another prison and was promised better treatment there. According to witnesses, she was transported alone, by Jeep, to Taganrog. Here, she was detained at a pre-trial detention centre known as Sizo 2:

“She arrived already pumped full of unknown drugs. She arrived and she basically started to go crazy”.

Ukrainian intelligence has recorded 15 fatalities at the prison, based on information from released troops. In the torture rooms, soldiers and civilians were water-boarded, beaten and shocked in an electric chair. When outside their cells, they were forced to adopt a stress position known as the swan – bent forward with their hands clasped behind their back at chest level. Food was severely rationed, with four and a half spoonfuls per plate, according to one detainee who counted.

For Roshchyna, the effect was catastrophic. She simply stopped eating. Recalled a witness, her temporary cellmate:

“We would talk to her but she was lost in her head, eyes terrified. Roshchyna would lie curled up fetal on the floor, behind a curtain that screened the toilet, out of sight of the guards”.

Her weight dropped to 30kg (66 pounds). She could stand up, but only with someone helping her. She was in such a state that she could not even lift her head off the pillow. Cellmates would prop her up and she would grab the top bunk to pull herself upright.

Roshchyna’s feet and legs swelled, according to her cellmate’s testimony. She was offered heart pills but appears to have refused these. Heart problems and fluid retention in the leg tissues are both signs of starvation.

In June, she was carried out on a stretcher. She spent several weeks at a hospital in Taganrog where, according to witnesses, she was watched over by six masked guards armed with machine guns. The level of security, and the efforts made to keep her alive, suggest Moscow saw her as a valuable negotiating pawn.

In July, she was reportedly sent back to Taganrog with an IV drip in her arm. It seems she continued to refuse food.

Colleagues began pulling strings. A message was sent to the Vatican, where Pope Francis, who had been able to communicate with Russia through backchannels, agreed to ask for her name to be added to the prisoner exchange list.

Word eventually reached her editor that she was to be released. Towards the end of August, Roshchyna was allowed to phone home. Her parents were told by the Ukrainian negotiators she was on hunger strike. They kept their mobiles switched on all day, waiting for her call. When she finally came on the line, Roshchyna was speaking in Russian. “I was promised that I would be home in September,” she told them. Her father urged her to eat. Then she said her farewells. “Well, that’s it. Bye, bye. Mom, Dad, I love you”.

On the 13th of September, bathed in autumn sunshine, 49 prisoners of war stepped off a coach from Russia on to Ukrainian soil. A welcome party met them with flags and bouquets of yellow sunflowers wrapped in blue tissue paper. Roshchyna’s cellmate was there, along with at least two other men held at Taganrog. But the journalist was missing.

Exactly why has never been made clear. On the 8th of September, Roshchyna was taken from her cell, ready for the long journey back to Ukraine. The anonymous detainee who cannot be identified for security reasons was one of the last to see her alive:

“We asked a girl from the cell to help her go down. With her help, she went down when they were supposed to exchange her. After that, a security officer came and said that the journalist never made it to the exchange. The officer added: ‘It’s her own fault'”.

Some weeks later, the deputy head of Russia’s military police wrote to Roshchyna’s father to say she had died on the 19th September 2023. No further information was provided. No further communications were made about her.

Workers in refrigerated lorries deliver the bodies of Ukrainian troops – and of Viktoriia Roshchyna – in February 2025.

In a pre-arranged exchange, on a lonely forest road in February 2025, along a line of refrigerated lorries, teams in hazmat suits went about their grim work: preparing the remains of 757 Ukrainian military casualties handed over by Russia for the journey back to Kyiv.

Clipboards in hand, intermediaries from the Red Cross checked their lists. For each body shrouded in white plastic, the Russians had provided a number, a name, a location, sometimes a cause of death.

And then, at the very bottom of the last page, a mystery entry: “NM SPAS 757″. The letters were abbreviations, taken to mean “unidentified man” and “extensive damage to the coronary arteries”. It would be weeks before officials could confirm the unlabelled remains were those of a woman. Not a soldier, either, but one of the most high-profile civilians detained since the full-scale invasion – Viktoriia Roshchyna. Packed in with the body was a tag with the handwritten inscription “V.V. Roshchyna”, and DNA tests matched with her parents.

Her father, in his grief, refuses to accept she is gone. He has requested additional examinations – all of which confirmed it was Viktoriia. He has continued to write letters, including to Taganrog, demanding information. The Sizo director, Aleksandr Shtoda, has replied twice claiming Roshchyna was never there. His most recent response, in January 2025, stated she “is not and was not listed in any of our databases”.

But what has repulsed the world and has shown what savages these Russians are was further details revealed by the forensic examiners:

• her brain, eyes and larynx were missing

• her hyoid bone in her neck was broken, the kind of damage that can occur during strangulation. However, the exact cause of death will never be known because of the missing parts.

• there were numerous signs of torture – burn marks on her feet from electric shocks, abrasions on the hips and head, and a broken rib. Her hair, which she liked to wear long and tinted blonde at the tips, had been shaved.

Roshchyna died after a year in detention, aged 27. Information on the specific circumstances and time of her death is limited.

In November 2022, Roshchyna described what motivated her. She had been given an award for courage by the International Women’s Media Foundation, but she did not want to stop work to attend the ceremony in Los Angeles and so she sent a message, hailing her colleagues:

“We have remained faithful to our mission, to convey the truth to the world, countering Russian propaganda. Unfortunately, many journalists have died, and will die. I want to dedicate this award to them. After all, they died in the fight for the truth, trying to record Russian crimes. I thank them”.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stood before a captivated audience of conservative activists from the U.S. and laid out his vision for American politics. The Western media, he declared at a May 2022 special meeting of the Conservative Political Action Committee in Budapest, are “the root of the problem.” The key to conservatives reclaiming power in the United States? “Have your own media”.

Orbán spoke from experience, having systematically reshaped Hungary’s political landscape since 2010, largely by reining in the independent press and replacing it with a loyal media apparatus. His advice, though at odds with democratic values, was warmly embraced by his American admirers, including conservative journalists, podcasters and political leaders.

Now, three years later, one particular political figure, President Donald Trump, appears to have taken Orbán’s words to heart, mimicking Orbán’s early actions and moving swiftly to dictate the terms of his own coverage.

New terms for the press

In his first 100 days, Trump asserted new control over the press, starting with those who cover him daily. In February 2025, his administration barred The Associated Press from the Oval Office for using “Gulf of Mexico” rather than adopting the president’s newly named “Gulf of America”. Soon after, Trump’s team stripped the White House Correspondents’ Association of its authority to decide which outlets are in the presidential press pool, a role journalists have held for over a century.

Then came a sweeping executive order in mid-March to dismantle government-funded news agencies, including Voice of America, the international broadcasting service. That same day, Trump went to the Department of Justice for a televised address, where he declared some of his negative press coverage was not just unfair but “totally illegal.” The president accused select media outlets of operating in “total coordination” to undermine him:

“These networks and these newspapers are really no different than a highly paid political operative and it has to stop, it has to be illegal”.

Now, Trump has escalated those demands, calling on the Federal Communications Commission to punish CBS and revoke its license over a 60 Minutes segment he didn’t like. He declared the network’s coverage “unlawful and illegal”.

From sidelining reporters to seeking legal retribution, Trump’s actions reflect not a series of isolated moves but a coordinated effort at media overhaul — one aligned with his broader attempt to restructure national institutions.

Having studied enough propaganda models and narrative control, I believe the likely source for this media overhaul playbook is Orbán.

The Orbán model

My media team has closely followed how Orbán consolidated control over the Hungarian press as prime minister, allowing him to project the illusion of media consensus and widespread support. His campaign began promptly after returning to power in 2010. With the backing of a new parliamentary majority, Orbán enacted a sweeping Media Act in 2011 that granted the state broad oversight powers. That meant a newly formed Media Council, staffed entirely by his ruling party, was given authority to fine news outlets for coverage they deemed “unbalanced or immoral”.

This was not merely an effort to temper criticism; it was the opening move in a broader strategy to remake Hungarian media.

The law drew sharp condemnation, most notably from journalists but also from the European Union. When Orbán later addressed the European Parliament, members protested by taping their mouths shut and holding signs that read “censored”.

To his critics, Orbán claimed that Hungary’s “media regulation system” had “collapsed” and that it was his government’s duty to rebuild it. But for the press, this was no reconstruction. As one Hungarian journalist put it, “Orbán saw the media as a battlefield; occupied by enemy troops and crowded with territories for potential expansion”.

Oligarchs take over media

The real takeover came through a coordinated wave of media acquisitions. Like pieces on a chessboard, Orbán-friendly oligarchs scooped up major newspapers, TV channels, and radio stations. His wealthy allies were systematic: They fired editorial teams, replaced critical voices with loyal ones, and often triggered mass resignations from journalists unwilling to toe the party line. Many once-independent outlets were soon resurrected as pro-Orbán media.

By 2018, the consolidation was complete.

In a display of political choreography, nearly 500 privately owned media outlets were donated to a central holding company: KESMA — the Central European Press and Media Foundation. Run by Orbán’s allies, KESMA now dominates Hungary’s media landscape, delivering a uniform stream of pro-Orbán content, promoting what he calls his “illiberal” agenda.

Orbán’s campaign offered a 21st-century model for media control — one rooted not in overt censorship but in narrative saturation. While some independent media remain, the vast chorus of pro-Orbán media now drowns out their dissent. It’s a model that has drawn admiration from right-wing figures around the world.

American media personalities such as Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson have traveled to Budapest to meet with Orbán and study his playbook, and reported back to Trump, while the Hungarian leader has become a star on the U.S. conservative circuit, speaking at Conservative Political Action Committee gatherings and forging ties with the MAGA movement and Trump. After joining him on the campaign trail last summer, Orbán boasted of his “deep involvement” in helping shape Trump’s upcoming agenda.

Importing the playbook

Looking back at the president’s first 100 days, it’s clear that Orbán’s tactics are now surfacing in Trump’s second term. Where Orbán passed a media law to penalize imbalanced reporting, Trump now calls certain coverage illegal, and his administration has begun investigations into at least one media outlet. He has also begun to sideline outlets that defy his agenda, as his press office continues denying access to wire services such as Reuters and Bloomberg.

Where Orbán’s allies acquired and repurposed unfavorable media, Trump has found powerful media partners of his own, such as Elon Musk. Musk’s 2022 takeover of Twitter, now X, mirrors the strategy of Orbán’s billionaire allies, allowing the tech mogul to effectively transform the platform into a megaphone for Trump’s agenda.

Finally, just as Orbán constructed a vast loyalist media network, Trump allies are expanding a parallel MAGA media universe designed to amplify and shield his message.

That apparatus is now a fixture of the White House. As independent outlets such as AP and Reuters are shuffled out, a new crop of pro-Trump voices are ushered in. Among them: Steve Bannon’s War Room, Real America’s Voice and Lindell TV, founded by MyPillow CEO and Trump advocate Mike Lindell. These networks don’t just cover the administration — they celebrate it.

Brian Glenn, a reporter with Real America’s Voice, was recently granted the first question in an Oval Office press event. He used it to praise Trump’s accomplishments and poll numbers: “All of your agenda that you ran on, you’re accomplishing that. You’ve got the support of the American people….If you can comment on the latest Harvard poll, I’d appreciate that”.

At another briefing, a Lindell TV correspondent asked press secretary Karoline Leavitt if she could share Trump’s fitness plan, remarking that he looked “healthier than ever,” and adding, “I’m sure everyone in this room can agree”.

Agreement is precisely the point. By recasting the media in his image, Trump is building a press pool that will champion his message. It is Orbán’s illusion of consensus, and this is just the opening act.

Trump’s war on the press has had a huge international impact too. Today’s Guardian has a special piece that examines why Russia and China are cheering on his attacks on the media, especially as they have resulted in the dismantling of Voice of America – the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda – as well as the U.S. Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas. This is, as one interviewee put it: “A cocktail for a misinformed world”. For the Guardian piece please click here.

Depending on how embedded you are in the journalism/media industry, the last 100 days have been a horror show. But I have been a media guy all my life so it is fascinating to me.

When I was a wee lad, around the age of 9 or 10, I started a weekly neighborhood newspaper – interviewing my neighbors, following local events, etc. One of my Mom’s friends ran a typeset print shop and he helped me design and set-up production. He eventually added a mimeograph machine to his business which made production and distribution of my weekly paper much easier. He eventually got me a job on our town’s local newspaper, running a newspaper delivery route (by bicycle). I eventually built it to over 100 customers. When I got older, the paper hired me as a freelance reporter.

The newspaper biz got into by blood.

At university I joined the radio station. In 1972/1973 I was studying at the University of Paris. My university radio station asked me to call in a report on the Vietnam peace talks. There I was, standing outside the Hotel Majestic on 27 January 1973, as the Vietnam War peace accords were formally signed and announced – not grasping the history unfolding. Later in my career, well after law school, and well into my lawyer career, I went to journalism school and to film school – in my 50s.

I am by profession a lawyer, a writer, a journalist, a media producer – and in my wildest dreams, a historian. As a lawyer I began my career working for clients in the technology, media, and telecom (TMT) sectors. I stayed in those sectors. It drew me to my own video and film production work, and although I am now semi-retired so I could write more, I still produce a bi-monthly newsletter for my TMT clients while my media team continues to produce bespoke videos for those clients. And I have jumped in and out of my genocide/Holocaust/perpetual-

But with the explosion of social media, the continuing Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces and the dispersion of creativity came the development of wonderful curation tools to parse a tsunami of information so readily available.

Like most of my media cohorts, I don’t “read” Twitter or Linkedin or any mainstream social media anymore. I use APIs like Cronycle and Factiva that curate the whole social media firehose so I only receive selected, summarized material that pertains to my immediate research or reading need. That led me to develop my own company, Luminative Media.

But really, if you look back at the development of digital media since the turn of the millennium, artists have been writing, and circulating their writing, like never before: essays, criticism, manifestos, fiction, diaries, scripts, and blog posts have charted a complex era in the world at large, away from mainstream social media, weighing in on the exigencies of our times in unexpected and inventive ways.

What is different is the level of social media toxicity and mis-information / dis-information /mal-information. And so one needs to set up some rules:

1. I use media (traditional or social) to become aware of things, but certainly not to reach conclusions on anything. What’s included and excluded, and takes upon it, are always subjective on anything as important as today’s catastrophes. As I have noted many times, to be an informed citizen is a daunting task. We move through myriad, overlapping spheres, ones that are forever entangled. All moving at an exponential pace. We are living through social and technological change on the scale of the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution. But occurring in only a fraction of the time.

Plus, what we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority, primarily but not exclusively governmental – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one. All of these other features are just the localized spikes on the longer sine wave of history. You need to do a lot of homework to get things right.

That is why, as I have noted, my media team and I receive and/or monitor about 3,500 primary and secondary resource points every month (about 120 items each day). But we use an AI program built by my CTO (using the Factiva research database + four other mediadatabases) plus APIs like Cronycle that curate the media firehose so we only receive selected material that pertains to our current research needs, or reading interest, which is coupled with an AI that summarizes each item, and links to the original source.

2. I make it a point to pay most attention to sources which are primary or near-to-primary as possible. So I read cover-to-cover the judgments and the official statements. And so far as journalism is concerned, I only pay attention to the most credible investigative type of material, based on documents and testimony from people directly involved, or people I have known and trusted through the years.

3. In considering official documents about serious allegations, serious matters, you need to pay attention to the precise wording to discover what is not being said, what agendas are hidden. What’s accepted (expressly or implicitly), what’s denied, what’s avoided, what’s recharacterised-then-denied. What’s between-the-lines. All those subtleties give clues as to where the real sensitivities and issues are.

But sometimes (sigh) you just need to step back and try to sense the humanity (and inhumanity) of it all.

Everyone, everywhere, lives by a story. This story is handed to us by the culture we grow up in, the family that raises us, and the worldview we construct for ourselves as we grow. The story will change over time, and adapt to circumstances. When you’re young, you tend to imagine that you have bravely pioneered your own story. After all, the whole world revolves around you.

As you age, though, you begin to see that much of what you believe is in fact a product of the time and place you were young in.

It was a study of the First World War that turned it around for me. It was monumental in scope, larger and more devastating than anything in anyone’s experience. The factors leading up to it were a confusing tangle of alliances, feuds, and rivalries, and the ordinary person might be hard-pressed to say just what they were fighting for. So many had died, and for what?

Oh, the complexity of the world. And the faux social environment that rewards simplicity and shortness, and punishes complexity and depth and nuance. I simply detest it. To understand the world you need to step outside your usual lanes, and cross disciplines, and cultural boundaries.

And I get it. It ain’t easy. I realize that many of my readers are “commerce monkeys, commerce machines” (not my turn of phrase – provided by a long time reader) – with barely enough time to read and write and produce for your jobs. You barely have time to scan and parse social media to keep up-to-date. I know. I know.

What we are experiencing today – the breakdown of all existing authority (primarily but not exclusively governmental) and the breakdown of all norms – is if not a predictable result, at least an unsurprising one if you read your history.

But still, though everything seems broken, we must still struggle with “why”, to struggle to understand – to struggle to survive. We are in the formative years of a new period whose name and character we don’t truly know yet.