How the forgotten Slapton Sands debacle improved allied chances in Normandy

6 June 2024 – There was a wonderful story on the BBC International channel last night. It was an interview with Ken Hay, and his participation in the invasion of Normandy 80 years ago today. The British Army veteran was captured a few weeks after the D–Day landings in northern France when his patrol was surrounded by German troops during the two-month battle for strategic high ground outside the city of Caen, known simply as “Hill 112”. Nine members of his platoon were killed that night. Hay spent the next 10 months as a prisoner of war.

Now 98 years old, he was asked how he intended to spent the day today and he said he wanted to talk to as many people as he could to make sure the experiences of those who fought and died to end the Nazi grip on Europe live forever:

“For many of us, as our time runs short, we have a need to try to keep our memories alive for others. We know this is likely to be our last major event to commemorate the sacrifices of those who fought and died to liberate France, and Europe. We are a tangible interpretation of what kids read in the books, what they’ve heard from their parents, their grandparents”.

No one knows exactly how many of the men and women who saw those events firsthand are still living. But they are 350 strong – from several countries – out at Normandy today. A buddy of mine is out there and he said it is thrilling to see these 98 and 99 and 100 year old guys talking about D–Day as if it was yesterday.

All this week Hay has been visiting schools to tell his story, so the battle to liberate France and defeat Nazi Germany doesn’t become a dusty relic of history like the Greek and Roman wars he read about as a child. He said his outreach isn’t to glorify war but to leave the message that “there must be a way, other than war, to resolve difficulties”.

And one hears that over and over from veterans. I had the privilege of attending the 75th anniversary at Normandy, and it was the same: even the youngest of those men and women who were nearing their 100th birthdays at the time knew their ranks were dwindling rapidly, and they felt a special imperative to tell their stories.

And today it is bittersweet. War rages across Europe – in Ukraine, Russian sabotage across multiple European countries, Islamic terrorism on the rise – so it is difficult to recognize the significance of that event 80 years ago.

And there are thousands upon thousands upon thousands of stories but I shall relate only one. But first, just a short history lesson … and a few more thoughts from Ken Hay.

Breaking through the Nazis’ “Atlantic Wall

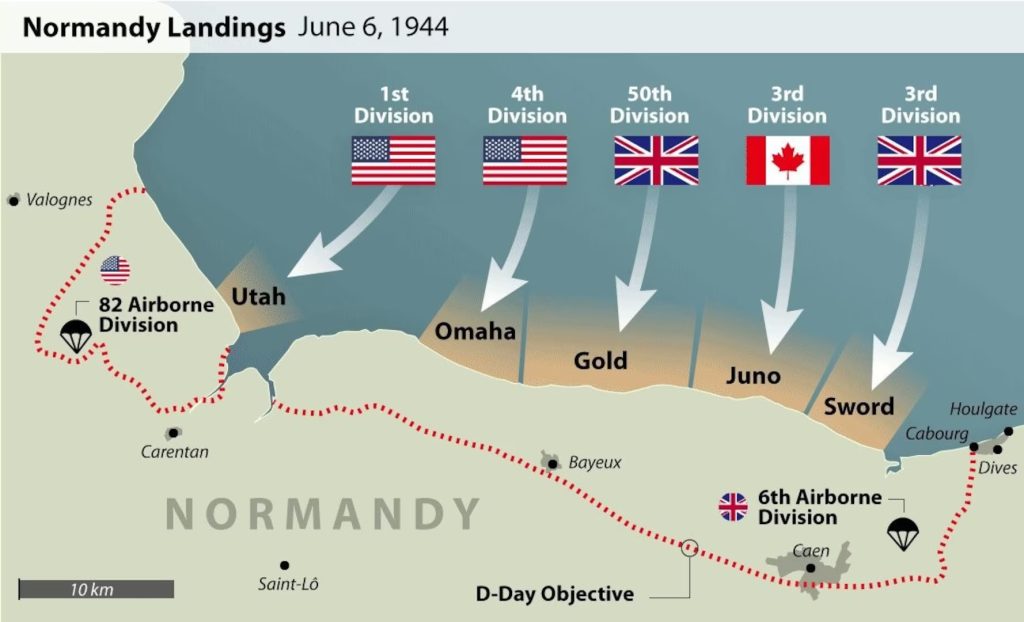

D–Day began in the early hours of June 6, 1944, when almost 160,000 Allied troops landed on the Normandy beaches or parachuted behind enemy lines to open the long-awaited second front in the war against Nazi Germany. At least 4,414 troops were killed and another 5,900 were listed as missing or wounded as Allied forces broke through the Nazis’ heavily fortified “Atlantic Wall” to secure a foothold in Northern Europe.

Note to readers: When a military operation is being planned, its actual date and time is not always known. The term “D–Day” was therefore used to mean the date on which operations would begin, whatever date that was. The day before D–Day was known as ‘D-1’, while the day after D–Day was “D+1″, and so on. This meant that if the date changed all other dates in the plan did not have to be corrected. The armed forces also used the term “H-Hour” for the start time.

By the end of August, more than 2 million forces from 12 Allied nations had crossed the English Channel, starting the march to Berlin that ended with Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945.

No one knows exactly how many of the men and women who saw those events firsthand are still living. There are about 350 at today’s events in Normandy.

Less than 1% of the 16.4 million Americans who served in the armed forces during World War II were still alive at the end of last year, and 131 are dying every day, according to estimates from the U.S. Veterans Administration. The senior historian at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans (a marvelous place to visit) noted:

“The actuarial tables tell us that pretty soon there won’t be a generation. And I think this 80th is the last round year in which we will actually be able to celebrate in the presence, and with the wisdom of, the veteran generation that actually fought the war”.

What’s being lost are the men and women who witnessed Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, the fall of France and the persecution of Jews now known as the Holocaust, then fought their way across Europe to defeat the Nazis.

In the U.K., the passing of the World War II generation was highlighted by the death in 2022 of Queen Elizabeth II, who trained as a military mechanic and truck driver during the final months of the war.

A moment of high drama

D–Day was the biggest operation of the war and a moment of high drama because everyone knew the Allies would invade Europe, they just didn’t know when or where. But 80 years later, many people’s vision of D–Day is being shaped by Hollywood productions such as “Saving Private Ryan”, not the experiences of the veterans who were there. A university professor friend of mone said:

You know, none of my students were even alive when that movie was made (1998), although almost all of them has seen it. This is something that, when they think of the Second World War, this is what they picture. It is difficult to discuss the actual war when tey say “Yeah, maybe, but in Saving Private Ryan …”. It is frustrating.

The success of D–Day wasn’t guaranteed

Allied commanders employed trickery, including a dummy army, to fool the Germans about where the invasion would take place and struggled to find a day with the right combination of weather, moon and tides to increase the chances of success.

They knew that failure would prolong the war, meaning more death and misery across Europe. A historian friend noted:

“It’s hundreds of thousands of military casualties, and we can only guess how many more civilian casualties of Hitler’s racial policies, his murderous racial policy. So you want to end this war and you want to end it quickly, and the path to do that is a successful landing in Western Europe”.

Even with the success of D–Day, Jews continued to die in Nazi concentration camps. Anne Frank, who spent more than two years hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam, listened to BBC reports of the D–Daylandings and wrote in her famous diary that the news filled her with “fresh courage”. Her family was arrested in August 1944 and she died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen in February 1945 … two months before the concentration camp was liberated.

Firsthand account of Nazi cruelty

Ken Hay recounted his firsthand account of Nazi cruelty. After he and four other members of his platoon were captured, they were shipped to Poland by train and put to work in a coal mine. As Russian forces closed in from the east in January 1945, the prisoners were marched back across the continent with little food or protection from the weather until they were freed by U.S. tank troops on April 22nd.

The two American soldiers who liberated him are the most important people in his life, Hay said, except of course for his late wife, Doris. They were married for 62 years. The man the kids named “Grandad Ken” talked about hunger and cold and pain. He held back on some details, though, afraid to tell the “kiddies” all the horrors he had seen.

The Slapton Sands Memorial

In the research I have done for my film and blog series on genocide, war and the political uses of massacre, I have come across thousands of stories, many of which I simply cannot use but that I store in my resaerch archive.

Last October in a trip to Scotland for a family event, a friend of mine took me to a lake area where you can still see the remains of the concrete docks and floating pontoons that were being tested in order to be able to get supplies and other materials ashore after the landings at Normandy – secretly planned and tested far from anybody’s eyes and ears. These shore areas in Scotland were similar to the harbor terrain and water conditions at Normandy.

But, my friend said, in a very sober voice, “let me tell you about Slapton Sands …”

As I noted in my post 5 years ago during the 75th anniversary of D–Day, many of the young men who went down with their ships during Normandy might not have been counted and recognized among the heroes of war. Hundreds of soldiers are still listed as “missing”.

But few know about “Exercise Tiger” at Slapton Sands in England, a devastating Nazi attack on Allied ships off the southern English coast, 39 days before the June 6, 1944 invasion. German intelligence had detected an Allied buildup of troops, personnel and ships in the vicinity of Lyme Bay, about 75 miles across the Channel from Nazi-occupied France. Luftwaffe spotters alerted the small Nazi S-1 torpedo boat fleet at Cherbourg, France, some of which slipped by British surveillance and scored a bloody victory. The fast-moving boats sank two of eight LST’s and damaged a third, killing at least 749 fighting men. Some historians said 1,000 sailors and soldiers had perished, one of the worst training disasters in U.S. military history.

The largest beachable landing ship developed by the Navy during World War II was the “Landing Ship, Tank” known as an LST, which would prove to be the real workhorse of amphibious invasions.

As my friend noted, God how the men must have suffered on those LSTs, which were lumbering easy targets. Not only those who drowned in the cold Channel waters, not only those who died instantly on the impact of the torpedoes. More than anything, the men trapped below deck. The immediate survivors would have died in the conflagration or suffocated. Legs would have been broken by the impact. “Death traps” he said – no chance to survive such an attack.

Preparing for the liberation of Europe, the Allied Command under Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had chosen Slapton Sands as the perfect spot for a dress rehearsal. The beaches on that coast were flat and lined by high bluffs, much like the Normandy landing zones.

The Allies assembled an impressive armada – 221 vessels, including eight LSTs, British support craft and smaller boats. Hundreds of troops loaded onto each of the landing ships, manned by officers and crew who were trained stateside. To make the rehearsal as real as possible, the trucks and tanks also onboard the 462-foot long LSTs were loaded with fuel, and all weapons carried live ammunition.

To date, the Allies had been expert in confounding and fooling German intelligence. They had invented fake troop movements and created airfields populated by ersatz balsawood planes and inflatable rubber tanks. They succeeded in confusing the timing of an attack and diverting attention away from the intended landing zone of the D–Day invasion.

Eisenhower’s brilliant move in 1944 to put the legendary (but troublesome) Gen. George Patton in charge of a phony invasion army helped fool the Germans about the real invasion. Nazi documents captured after the war showed Hitler and his command were convinced Patton would lead the invasion force – far from Normandy. But many German generals (including Herman Goering) thought otherwise.

At Slapton Sands, Eisenhower was not so lucky in the deceit department. As “Exercise Tiger” launched before dawn on April 28, 1944, Nazi analysts were on the lookout. German reconnaissance detected unusual ship movement along Lyme Bay. Luftwaffe reconnaissance spotted the troop and equipment concentrations along the coast and radio surveillance confirmed what they saw. Intelligence officers relayed their findings to the German S-Boat squadron based across the Channel at Cherbourg.

Under a dozen of the highly maneuverable S-boats skirted detection when they left their base and raced across the water to attack. The “Exercise Tiger” fleet had established radio silence except for emergencies, but the Nazis knew what they were doing. When British spotters detected the marauders, they broke silence only to find that a typo in the order of battle plans had provided faulty radio frequencies.

Three of the eight LSTs were hit. One made it to shore, A second exploded in flames, accelerated by the fuel laden vehicles on the loading deck. A third LST was blasted so fully that it sank within six minutes. In a history of the event by Lt. Eugene E. Eckstam, a medical officer aboard the first LST that sank, he said:

“We sailed along in fatal ignorance. We sat and burned, gas cans and ammunition exploding and the enormous fire blazing only a few yards away”.

The official account said the attacks killed untold “hundreds of men. Some of them succumbed to blast injuries and burns, others to drowning or hypothermia”.

There was little time for launching lifeboats. Trapped below decks, hundreds of soldiers and sailors went down with the ships. Others leapt into the sea, but many soon drowned, weighted down by water-logged overcoats and in some cases pitched forward into the water because they were wearing life belts around their waists rather than under their armpits. Others succumbed to hypothermia in the cold water.

News of the disaster was withheld for a time by the Allies, not only for morale but to withhold potentially helpful information about the coming invasion from the enemy. It was duly reported a month after D–Day.

The deaths off Slapton Sands, though horrific, were not in vain. The Allied command tried to correct the mistakes of the exercise; they redesigned life preservers and trained sailors and soldiers how to use them. They instituted new procedures for rescuing men knocked overboard. They chnaged the configuration of the landing boats. They also locked down security and maintained secrecy up until the Normandy invasion.

Meanwhile, with the Luftwaffe already depleted, Slapton Sands showed that the Nazi S-Boats were the greatest remaining threat in the English Channel. By the end of June, the Royal Air Force had disabled or destroyed them all.

Even as the first troops were landing on the morning of June 6th, the bulk of the Nazi defense force was concentrated 150 miles north of the invasion beaches, around Calais, waiting for Patton, thanks in large measure to Eisenhower’s magnificent deception ops. Ike’s prediction on the eve of D–Day would prove true, that the invasion led to “the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.”

The U.S. quickly put its full weight behind the island hopping campaign in the Pacific to defeat Japan.