4 July 2017 – Amazon’s deal to buy Whole Foods may be remembered as the dawn of a new era in business, when an old industry stubbornly resistant to change suddenly gave way to something modern and innovative. But supermarkets were once themselves a cutting-edge concept.

It wasn’t that long ago that shoppers went to the butcher for meat, the baker for bread, and the green grocer for produce. Starting in 1930, the supermarket pulled it all together. The bounty of the American supermarket, with its towers of toilet paper and freezers full of meat, was so arresting to Soviet officials who visited one in 1989 that it shattered their faith in communism and helped end the Cold War.

As Oliver Staley (a blogger for Quartz and an agenda contributor to the World Economic Forum) pointed out on his blog last week:

Modern supermarkets were made possible by a host of changes, from industrial-scale farming to the interstate highway system. But after pioneering a logistics revolution that paved the way for shopping malls and big-box stores, progress pretty much stopped. While virtually every other domain of commerce has changed dramatically with the advent of the internet, online grocers were stymied by the challenge of delivering perishables while operating within the tight margins that make groceries a competitive business.

Why is this time different? Part of it is the track record of Amazon and Jeff Bezos; from books to television shows, there is little, if anything, they haven’t been able to sell online.

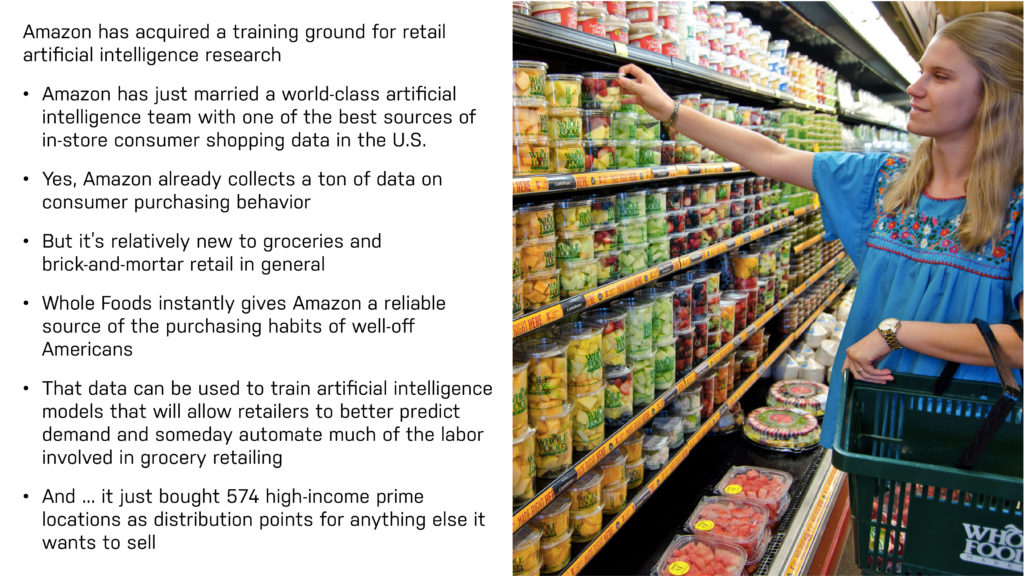

But the “real deal” behind this is artificial intelligence. Two weeks ago I gave the keynote address in Zurich at the Digital Investigations Conference (“Artificial Intelligence, My Implausible Reality”). The Amazon/Whole Foods deal had been announced a few days before my presentation so I quickly pulled together the next two graphics:

I have been a customer of Amazon for rather longer than I have been a shareholder. But in either capacity I have always struggled to understand how the company has disappointed, the usual mantra when Amazon profits miss the mark. I am guided by this:

Amazon’s market value

2006: $17.5 billion

2017: $461 billion

Growth over ten years: 2,534%

Bezos has delivered — and continues to deliver — precisely what he promised he would almost two decades ago. In fact, if you go back to his very first letter to shareholders in the annual report that appeared following the company’s listing in 1997 (each year he actually re-prints that letter alongside the current version) under the heading “It’s all about the Long Term” he declared:

“We believe that a fundamental measure of our success will be the shareholder value we create over the long term. This value will be a direct result of our ability to extend and solidify our current market leadership position. The stronger our market leadership, the more powerful our economic model. Market leadership can translate directly to higher revenue, higher profitability, greater capital velocity, and correspondingly stronger returns on invested capital. Because of our emphasis on the long term, we may make decisions and weigh trade-offs differently than some companies . We are working to build something important, something that matters to our customers, something that we can all tell our grandchildren about. Such things aren’t meant to be easy.”

It is true that from time to time the stock market has failed to understand the company’s strategy, true also that there have been some false starts along the way, which Bezos is among the first to admit. Value creation of $461bn does not come without taking risks or making mistakes. Some investors may prefer companies that focus on reporting smooth, consistent earnings and distribute these profits to shareholders rather than reinvesting them for the future. Amazon was from its inception never going to be one of these companies.

But there is evil at work, too. With his acquisition of Whole Foods, Bezos has made clear his determination to dominate every facet of mass retailing, likely at the cost of massive layoffs in the $800 billion supermarket sector. But this, if anything, understates the ambitions of America’s new ruling class, almost entirely based in San Francisco and Seattle, as it moves to take over industries from entertainment and transportation to energy and space exploration that once thrived and competed outside the reach of the oligarchy. I am reminded of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’ famous dictum:

“We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

Brandeis posed his choice at a time when industrial moguls and allied Wall Street financiers dominated the American economy. Like the oligarchs of the past, today’s new “Masters of the Universe” are reshaping our society in ways that could, if unchallenged, undermine the foundations of our middle-class republic. This new oligarchy has amassed wealth that would impress the likes of J.P. Morgan. Bezos’ net worth is a remarkable $84.7 billion; the Whole Foods acquisition makes him the world’s second richest man, up from the third richest last year. His $600 million gain in Amazon stock from the purchase is more than the combined winnings of Whole Foods’ 10 top shareholders. Bezos wants to “reorganize the world, as an Amazon storefront” (a quote from an excellent piece by Victor Luckerson).

But before I get onto the vapid employment of antitrust to block the tech oligarchs’ domination of key markets like search, social media, computer, and smartphone operating systems, a few notes on the “new new” thing behind the Bezos move.

The next “new new” thing

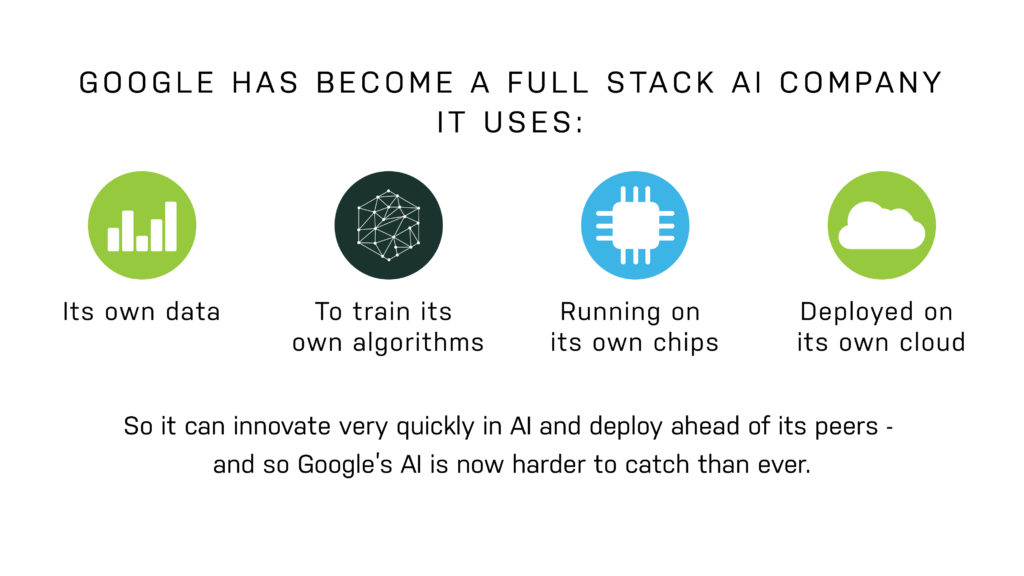

As I have noted before, machine learning/artificial intelligence really requires massive volumes of data filtered through algorithms to create systems that continuously learn from the information fed back into them. Google is the King because it is the only full stack AI company … the “new new” thing … and Amazon must challenge it:

The only companies that will be able to compete are companies like Apple, Amazon and Facebook who have some (and quite close to all) of those 4 elements because they, too, need to be full stack AI companies.

The result is that Google is able to innovate very quickly in AI and deploy it ahead of its peers—just like Apple took full control of OS and chip development for the iPhone. By becoming world-class at four layers of the tech stack, Google’s AI is now harder to catch than ever. Let’s take a quick look at each stack (a summary from an ARK Investment analysis).

Data

Data is the fuel for AI, and Google owns some of the largest data sets in the world. The company operates seven services with over a billion monthly active users: Android, Chrome, YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps, Google Search, and Google Play. In addition, Google Translate and Google Photos are used by over 500 million people each. By operating such a diverse range of services, Google collects data of various types: text, images, video, maps, and webpages — helping the company master not just one kind of AI, but AI across various use cases.

NOTE: Facebook is probably about to attain the holy grail of image search as its AI has now achieved the ability to search photos by what’s in them. More on that in a subsequent post.

It also explains the utter failure of a “state-of-the-art” photo recognition software by a prominent e-discovery company. E-discovery companies do not have, will never have the massive data sets necessary to make machine learning work in key areas. Which is why these companies are seeking alliances with Google, Facebook and Microsoft. More in a subsequent post.

Just as important as the data are the apps, which Google also owns. The apps are the front end to algorithms, giving Google’s AI efforts a tremendous distribution advantage. A startup might achieve a breakthrough in an AI vertical, but reaching hundreds of millions of users could take years. The same breakthrough in Google’s hands could be “turned on” for a billion users overnight. Users benefit immediately, while Google’s products become sticker and more valuable.

Algorithms

At its core, Google is an algorithms company — it invented Page Rank, the algorithm behind Google Search. Not surprising, Google was one of the first companies to adopt deep learning and arguably is the industry leader when it comes to deep learning research. Google, along with its UK subsidiary, DeepMind, has created novel deep learning architectures that address a wide range of problems, notably:

- Inception – a convolutional neural network that is more than twice as accurate as and 12 times simpler than prior models;

- Neural Machine Translation – a deep learning based translation system that is 60% more accurate than prior approaches;

- WaveNet – a deep learning voice engine that generates spoken audio approaching human level realism;

- RankBrain – a method to rank web pages using deep learning that is now the third most important ranking factor for Google Search; and

- Federated learning – a distributed deep learning architecture that performs AI training on smartphones instead of relying exclusively on the cloud.

While other companies like Facebook and Microsoft also have created novel deep learning algorithms, Google’s research breadth and user scale are unmatched in the industry. By publishing the results, Google further cements its reputation as the leader in AI, attracting the next wave of talent and thus creating a fly-wheel effect in algorithm development.

Hardware

In 2016, Google announced that it had built a dedicated processor for deep learning inference called the Tensor Processing Unit (TPU). The TPU provides high performance in deep learning inference while consuming only a fraction the power of other processors.

Google’s first generation TPU can perform 92 trillion operations per second and consumes 75 watts of power: its per watt performance equates to 1.2 trillion operations per second.

Cloud

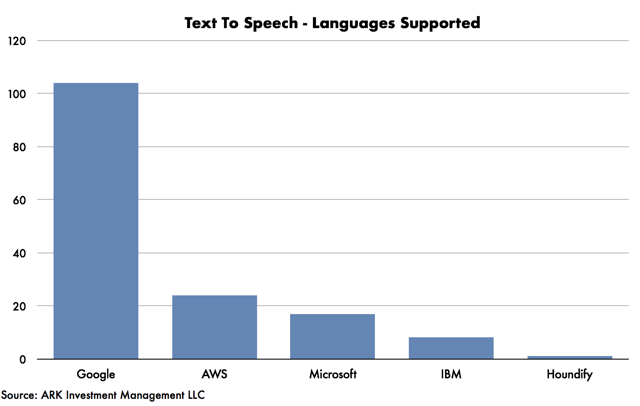

In the cloud computing business, specifically Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Google currently is in third place, behind Amazon and Microsoft. One space in which Google leads, however, is cognitive application programming interfaces, or APIs.

Cognitive APIs leverage the power of the cloud to perform narrow AI tasks such as image recognition, text transcription, and translation. Unlike IaaS, which serves up commodity hardware in the most cost effective manner, the performance of cognitive API varies significantly from one vendor to another, a function of the algorithms, training data, and underlying hardware.

NOTE: based on ARK’s research, these three factors favor Google: it has the most advanced algorithms, the largest dataset thanks to multiple billion-plus user platforms, and the most powerful and efficient hardware thanks to its TPU.

So …. Google’s AI efforts have built a fully integrated company that spans algorithms, data, hardware, and cloud services. This approach helps funnel the world-class AI of Google’s consumer products to its enterprise offerings, providing Google Cloud with a competitive edge. Bringing chip design in-house increases Google’s AI moat by improving performance, lowering latency, and reducing cost. Perhaps most critically, vertical integration enhances its organizational agility: Google can steer all parts of its organization to bring a new product or service to market. Consequently, Google’s AI will be at the forefront of the innovation for years to come.

With Amazon … especially Amazon … and Apple and Facebook and Microsoft all in hot pursuit.

Antitrust issues? What antitrust issues?!

It’s behavior, stupid!

When I began reading the analysis of the Amazon/Whole Foods deal by the legal pundits all the views were identical: the U.S. regulators might look at antitrust issues regarding this merger but there would be no concerns because the industries are different.

As always, the law is an ass. And the law will always be years and years behind the society it ostensibly regulates. New technologies often have a way of making old laws seem obsolete. And that can set off a flurry of fumbling, half-hearted activity at every level, from cities and towns to states to the federal government, as lawmakers try to catch up and fill any gaps.

The issue? These industries are EXACTLY the same: it’s all about human behavior. Any antitrust investigations should consider the aggregation of data, the predictability of behavior, and how Amazon as a mega retailer can manipulate behavior. Nobody who shops at Whole Foods has given the company the authority to sell their customer shopping habits — which are identified by your name, credit card number and zip code — to the behavioral technologist charlatans at Amazon.

More than antitrust, however, it should be illegal for internet companies to manipulate behavior online. It’s not a stretch to see that Amazon could very well suggest sombre music, a sad movie, show various depressing pictures, then have Instacart arrive with overpriced ice cream and cookies.

And, dear regulators, longer term, look at this as an even smarter, more anticompetitive play by Amazon: it gets 574 distribution points around the world, and millions of customers it can tap into to whom it can sell all of its other services. It’s easy to imagine big discounts on food if you happen to use Amazon Alexa, Amazon Video and are a Prime subscriber.

NOTE: Amazon Alexa now enables shopping without computer, phone, or TV … one stop shopping via a vocal action alone. The only stipulation is that you need to be an Amazon customer, preferably Amazon Prime. They already indicated they will tie in Whole Foods.

There’s a reason other companies, like Facebook, are expanding into other verticals such as AI, virtual reality and even internet programs for Africa – they’re looking to spread their tentacles and it turns out the real world is a great place to do it.

It is the power of the “Fangs” (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google), an acronym coined by a reporter on a U.S. business cable show in 2013 to denote the companies in Big Tech that had become the new Wall Street and had bifurcated the world, economically, socially and legally.

I am old enough to have lived through one big boom-and-bust tech cycle. Indeed, I worked for Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison from 1998 to 2000, so I was at “Ground Zero” of the melt-down. The levels of hubris today are similar but, more pernicious, given that the largest technology companies have become the systemically important institutions of our day. Like the big Wall Street banks, they hold vast amounts of money and political power and even greater troves of data. Facebook has more users than China has people. Silicon Valley operates more or less exclusively on the notion that it is making the world more free and open, despite growing concerns that social media has eroded democracy and predatory algorithms are targeting the weak and vulnerable, in the same way that pre-crisis predatory lending did.

The Valley has clearly moved away from its hippy, entrepreneurial roots. Big Tech chief executives are as rapaciously capitalist as any financier, but often with an added libertarian bent in which anything and everything — government, politics, civic society, and law — can and should be disrupted. Another book I highly recommend is Jonathan Taplin’s Move Fast and Break Things, which tracks the evolution of the Silicon Valley political economy and antitrust avoidance.

And what is a “monopoly” has changed meaning

When I was in law school in the mid 1970s I had the good fortune to take a course in antitrust economics, taught by a lawyer/economist. We used Ernest Gellhorn’s then standard text on the subject. Having been an economics major in college and having worked on Wall Street for 3 years before going to law school and seeing a lot of this stuff “in action”, the course really stuck with me. Today my e-discovery staffing unit often works with Frontier Economics, an EU-wide microeconomics consultancy that provides economics advice to public and private sector clients on matters of competition policy, antitrust, etc.

One of my first lessons in that course contrasted perfect competition, which was judged to be a good thing, with monopoly, which was not. There are worse places to begin than by being shown the difference between championing the miracle of the free market and favouring the depredations of dominant businesses. But monopoly power has often seemed like yesterday’s issue. Standard Oil was broken up in 1911; AT&T in 1984. To the extent that economists worried about companies being too big, they have often been thinking about the systemic risks from banks that were too big to fail.

But now when you look around the world you start to notice that the risks are not of corporate failure but of corporate success. The most obvious examples are the big digital players: Google dominates search; Facebook is the Goliath of social media; Amazon rules online retail. And as documented by numerous working papers, American business in general is becoming more and more concentrated.

Frontier Economics has looked at 676 industries in the US — from cigarettes to greeting cards, musical instruments to payday lenders. They found that for the typical industry in each of six sectors — manufacturing, retail, finance, services, wholesale and utilities/transportation — the biggest companies are producing a larger share of output. For example, in the early 1980s the largest four players in any given US manufacturing industry averaged 38 per cent of sales; three decades later the figure was 43 per cent. In utilities and transportation the typical market share of the biggest four companies rose from 29 per cent to 37 per cent.

In retail, overshadowed by Walmart and Amazon, the rise was dramatic: 14 per cent to 30 per cent.

This is surprising. As the world economy grows, one might expect markets to become more like the perfectly competitive textbook model, not less. Deregulation should allow more competition; globalization should expose established players to pressure from overseas; transparent prices should make it harder for fat cats to maintain their position. Why hasn’t competition chipped away at the market position of the leading companies? The simplest explanation: they are very good at what they do. Competition isn’t a threat to them. It’s an opportunity. It’s why in the current literature you read that “superstar firms” tend to be more efficient (to get a grip on this “superstar” competitive concept, start with the flood of articles that have appeared over the last 5-6 years in the Harvard Business Review). They sell more at a lower cost, so they enjoy a larger profit margin. Google is the purest example: its search algorithm won market share on merit. Alternatives are easily available, but most people do not use them. But the pattern holds more broadly: superstar firms have grown not by avoiding competitors but by defeating them.

And they have taken advantage of one of the most significant changes in antitrust law and interpretation over the last century: the move away from economic structuralism, replaced by price theory.

Amazon’s antitrust paradox … and “economic structuralism”

Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. Bang. Full stop. No argument. In addition to being a retailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Yes, it has clocked staggering growth, yet generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and expand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e-commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for thousands of other businesses that depend upon it. Lina Hahn (coming out with a book on Amazon this fall) uses two quotes:

“Even as Amazon became one of the largest retailers in the country, it never seemed interested in charging enough to make a profit. Customers celebrated and the competition languished.”

—The New York Times (2014)

“One of Mr. Rockefeller’s most impressive characteristics is patience. He routinely slashed prices in order to drive rivals from the market. Standard Oil charged monopoly prices in markets where it faced no competitors; in markets where rivals checked the company’s dominance, it drastically lowered prices in an effort to push them out.”

—Ida Tarbell, A History of the Standard Oil Company (1905)

Elements of Amazon’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns — yet it has always escaped antitrust scrutiny. Why? Because the current framework in antitrust — specifically its pegging competition to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects — is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy, captured by such new technologies as artificial intelligence and gargantuan databases. Further, anti-competition frameworks just do not “get” platforms. Quoting Lina Hahn:

First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have rewarded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible.

Second, because online platforms serve as critical intermediaries, integrating across business lines positions these platforms to control the essential infrastructure on which their rivals depend. This dual role also enables a platform to exploit information collected on companies using its services to undermine them as competitors.

The many facets of Amazon’s dominance is brilliantly explained in the Brad Stone book The Everything Store, a book pilloried by both Bezos and his wife … yet he made available on Amazon. It became a best seller. I loved the book. Though Bezos wouldn’t give Stone an interview, he allowed numerous people in his world, including multiple key Amazon executives, to talk to Stone. The result is an authoritative, deeply reported, scoopalicious, nuanced, and balanced take that pulls absolutely no punches. It is a thorough explication of how Bezos built the company, his strategic and tactical methods, his approach to hiring, how Amazon navigated Wall Street, and how it approaches new markets. It shows Bezos to be a sponge for information, and a fearless inquisitor, approaching even seasoned competitors to soak up knowledge from them … this latter point, incidentally, being one of the many qualities Bezos shares with Steve Jobs.

So this is the book you need to understand all of these facets and to make sense of the Amazon business strategy, to illuminate the anticompetitive aspects of Amazon’s structure and conduct, and to understand the deficiencies in the current U.S. antitrust doctrine.

Because in some ways, the story of Amazon’s sustained and growing dominance is also the story of changes in U.S. antitrust laws. Due to a change in legal thinking and practice in the 1970s and 1980s, antitrust law now assesses competition largely with an eye to the short-term interests of consumers, not producers or the health of the market as a whole, or the direction of markets; antitrust doctrine views low consumer prices, alone, to be evidence of sound competition. By this measure, Amazon has excelled; it has evaded government scrutiny in part through fervently devoting its business strategy and rhetoric to reducing prices for consumers. Amazon’s closest encounter with antitrust authorities was when the Justice Department sued other companies for teaming up against Amazon. Lina says:

It is as if Bezos charted the company’s growth by first drawing a map of antitrust laws, and then devising routes to smoothly bypass them. With its missionary zeal for consumers, Amazon has marched toward monopoly by singing the tune of contemporary antitrust.

Because what the antitrust regulators should do is return to economic structuralism which is the idea that concentrated market structures promote anticompetitive forms of conduct. That you need to analyze the underlying structure and dynamics of markets. Rather than pegging competition to a narrow set of outcomes, the approach examines the competitive process itself. It’s the idea that in the twenty-first century marketplace with its incredibly complex architecture of market power a company’s power and the potential anticompetitive nature of that power cannot be fully understood without looking to the structure of a business and the structural role it plays in markets.

Lina Hahn:

Simply put: seeking to gauge a firm’s market role by isolating a particular line of business and assessing prices in that segment fails to capture both (1) the true shape of the company’s dominance and (2) the ways in which it is able to leverage advantages gained in one sector to boost its business in another.

POSTSCRIPT: GOOGLE’S $2.7 BILLION FINE FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION

Our media group is actually producing a 4-part video series on the Google/EU case which will air end of September. Using video interviews, motion graphics, etc. we figured this stuff was much more fun to watch than read about. So herein just a few, cursory notes:

- The problem regulators are trying to correct is easy to visualize — just think of the last time you were browsing for a product online and typed it into your search bar on Google. The first thing to come up is typically the sponsored Google Shopping tab. That prime placement for Google at the top of the browser meant competitor comparison shopping sites were pushed further down, and often ignored by consumers.

- The increased clicks to Google Shopping meant ballooning traffic for the tech giant. It was very bad news for its competitors, some of whom were not able to regain their lost web traffic.

- The reasons for the fine are fairly tedious, even by the usual standards of EU bureaucratic action. The specific Google product at issue isn’t well-known or widely used and the specific companies involved aren’t well-known either.

- The EU has a reputation for being the tough cop on the block when it comes to competition laws, far more so than the US. A big part of the reason for that is antitrust prosecutors in the US can seek jail time for erring companies in addition to fines, and therefore have to establish a higher burden of proof for wrongdoing.

- European regulators, on the other hand, just impose fines, and don’t have to prove their case to a judge.

- The Google case is part of a larger trend of EU regulators taking a critical look at Silicon Valley titans, including Apple, Amazon, and Facebook. Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s competition regulator, ordered Apple to pay billions in back taxes owed to Ireland last year, and is also investigating Facebook for its use of consumer data.

- The fine itself is a drop in the bucket for Google and its parent company Alphabet, which post annual revenues of more than $90 billion. However, the announcement sent the company’s stock into a downward spiral.

For the EU, the bottom line is that Google has too much power across too many markets.The result is that for now at least the United States and Europe appear to be headed down two very different paths with regard to the application of antitrust law to digital technology. The American philosophy emphasizes the risk that overly zealous regulation could constrain innovation from some of the most dynamic companies on earth while the European one emphasizes the risk that those companies themselves have grown so large and powerful that they can choke off new players. They diverge in part on how they think about “network effects” as a moat in the modern economy, and in part on their specific assessment of Google’s business decisions.

NOTE: I do not have the space to give a full treatment to “network effects” ((increases in usage lead to direct increases in value). Facebook is good to use in part because it’s a good product, but in part because everyone is already on Facebook. Even if a rival social network product came along that was, all things considered, slightly better, nobody would use it because nobody else is using it.

Google, by the same token, has a nearly insurmountable lead over every rival in virtue of the fact that so many people are googling all the time. Each search is an input into Google’s ongoing iterative machine learning that aims to get better and better at surfacing the most relevant content. No rival can match Google’s user base, so no rival can match the speed at which Google is learning and getting better. That gives Google considerable latitude to mess around with how search works to promote its own products while still maintaining a dominant basic position in search.

During the landmark antitrust litigation against Microsoft in the 1990s, this was exactly the position the US government took.

But they also diverge in how they think about the purpose of competition policy. American regulators take a relatively narrow view that the goal should be to prevent consumers from facing situations in which they have no choices, or in which lack of choices forces them to pay higher prices. European regulators take a broader view that the goal should be ensure the viability of a diverse ecosystem of firms. The American view is that excessive regulation is a clear threat to innovation, while the European view is that a corporate monoculture is a clear threat to innovation.

Final note on Google’s power …

If you do a web search on your mobile phone, you are probably looking at what’s known as an Accelerated Mobile Page. AMP is a Google initiative to make mobile web pages load at lightning speed through a combination of stripping them down and hosting the content directly on Google’s servers.

One reason publishers have adopted AMP is that the technical performance really is impressive. But as critics like Jon Gruber have long pointed out, it also has significant downsides not least of which is you are wiping out publishers’ independence, ceding everything to Google. And Facebook.

Given the tradeoffs, the real answer to his question “Can someone explain to me why a website would publish AMP versions of their articles?” is extremely simple:

Publishers do it because Google wants them to do it. They perceive that AMP pages will be favored over non-AMP ones in Google’s search, and so if you want to maximize your search referral traffic you ought to do what Google wants and get on the AMP train.

One Reply to “Amazon eats the world: it’s about artificial intelligence, it’s about the next “new new” thing … and it’s about laughing in the face of antitrust regulators”