31 October 2016 (Milos, Greece)– Last week I was at the IoT Solutions World Congress and obviously we could not avoid discussing the internet’s “Main Event” from two weeks ago: a massive chain of hacked computers simultaneously dropped what they were doing and blasted terabytes of junk data to a set of key servers, temporarily shutting down access to popular sites in the eastern U.S. and beyond. Unlike previous attacks, many of these compromised computers weren’t sitting on someone’s desk, or tucked away in a laptop case – they were instead the cheap processors soldered into web-connected devices, from security cameras to video recorders.

I wrote about it briefly here but after several conversations at this Congress a more detailed piece will follow. I had a walk-through of the process of how publicly available source code is used to to assemble a bot-net army of internet-enabled devices, and then directs those devices to send massive waves of junk requests to a major DNS provider. It was an education.

As you might expect at a technology conference such as this, there is much to write about. Most will require more detailed follow-up posts. For instance, one of the more interesting themes … which most did not wish to discuss, but many did; after all, it was not a security event, it was a trade show … was the mantra “Protection is dead. Long live detection. As critical as it is, protection will fail. You need robust detection”. Networks will be breached. USB drives will be lost. Users will click on and respond to phishing messages. Malicious insiders will abuse their privileges to steal information and cause damage. Well-meaning insiders will accidentally delete data. Russia, China, organized crime and other traditional advanced persistent threats will compromise even the most sophisticated protection mechanisms.

Robust detection. That’s the ticket. The security folks were most happy to discuss so a more detailed post to come.

For this piece I will limit my discussion to:

– a chat with Kaspersky Lab

– a panel discussion on data ethics with some legal analysis … like “litigation-as-a-driver”?

1. The Internet of Harmful Things

In the early 2000s Eugene Kaspersky used to get up on stage and prophesize about the cyber-landscape of the future, much as he still does today. Back then he warned that, one day, your fridge will send spam to your microwave, and together they’d DDoS the coffeemaker. No, really. I’ve seen the video clips. As he tells it:

“The audience would raise eyebrows, chuckle, clap, and sometimes follow up with an article on such ‘mad professor’-type utterances. But overall my ‘Cassandra-ism’ was taken as little more than a joke, since the more pressing cyberthreats of the times were deemed worth worrying about more. So much for the ‘mad professor’… just open today’s papers.

The Kaspersky team ran through the history of “smart” devices and named but a few: phones, TVs, IP-cameras, refrigerators, microwave ovens, coffee makers, thermostats, irons, washing machines, tumble dryers, fitness bracelets … oh, lots more. I stopped taking notes. And they said some houses are even being designed these days with smart devices already included in the specs, often without the full details known to the owners. And all these smart devices connect to the house’s Wi-Fi to help make up the gigantic, autonomous – and very vulnerable – Internet of Things, whose size already outweighs the traditional Internet which we’ve known and loved since the early 1990s.

Connecting everything (including the kitchen sink) to the Internet is done for a reason, of course. Being able to control all your electronic household kit remotely via your smartphone can be convenient (to some folks). It’s also rather trendy. However, just how this Internet of Things has developed has meant Eugene Kaspersky’s Cassandra-ism has become a reality.

The DDoS attack I noted above was launched by the Mirai botnet (which I briefly discussed in my earlier piece) made up of IP-enabled cameras, DVRs and other connected bits of IoT kit. Mirai turned out to be rather simple malware, which scans the Internet for IoT devices, connects to them using default logins and passwords, secures admin rights, and carries out the commands of the hackers. And since it’s rare that a user changes the default login and password on such devices, recruiting several hundred thousand zombies for the botnet was pretty straightforward.

So, a simple botnet created by amateurs and made up of all sorts of smart devices was able to severely disrupt some of the largest Internet sites in the world for a time. A network designed to withstand nuclear attack, brought down by toasters.

The botnet has shown up before: in the most powerful DDoS attack ever known, which targeted Brian Krebs’ blog (with a peak power reaching 665 Gbps).

It’s the same old story: the IoT “Gold Rush”. In the race for better functionality, the race-to-the-market, IoT manufacturers have neglected security. But the history of the internet of things reveals some hints about why so many connected gizmos are virtual time bombs. The internet of things very much parallels the way the internet grew up. We rushed to it so quickly that security was largely left behind – in part because it was so awesome. I mean, really: who doesn’t need a refrigerator that can reorder milk for you on demand?

The litigation lawyers, smelling blood, have been all over this latest DDoS attack – but stymied. When it comes to a botnet – a zombie horde of devices that have been hijacked to do a hacker’s bidding – things get complicated. Who can claim harm when millions of unsuspecting webcams and DVRs start attacking a single target? It might be the person who bought the device because it runs more slowly or doesn’t function as intended. Or it could be the target of the coordinated attack: Krebs, for example. The internet infrastructure that came under siege from that DDoS attack two weeks go belonged to a company called Dyn – but the ensuing outage affected millions across the U.S. Who can claim injury there? The answer isn’t yet clear.

I spoke with two attorneys … both cybersecurity lawyers … and they were of the opinion that an individual or a company could sue manufacturers of faulty devices directly for their negligence. Their point was the legal framework for such a suit may already exist in tort and contract law. A manufacturer would be in breach of contract, for example, if it sold a product it claimed was safe but that wasn’t. But both admitted a civil suit against a manufacturer for leaving its products vulnerable to botnets would take a “smart and creative lawyer”. And without some sort of legal risk for device manufacturers that put out faulty and dangerous machines, the lawyers agreed, it could be very hard to raise the standard of internet-of-things security. Of course, for attorneys who specialize in cybersecurity, more internet-security regulations usually means more work.

And let’s face it: regulation — especially in dizzyingly fast-developing technology — always comes with drawbacks. Government has not shown that it can keep pace with nascent technologies, so creating a flexible enough framework that protects consumers while leaving room for growth would be a formidable challenge.

But oh those dangers out there. Mirai’s size is estimated to be of around 550,000 bots, while the whole of the IoT is thought to be made up of somewhere between seven and 19 billion devices (in five years it’s expected to go up to 50 billion). So, how many of those are vulnerable? How many can be recruited for hacker attacks? That’s a tricky one to answer, but the Kaspersky folks made a few points:

“One thing for sure is that Mirai has lots and LOTS of potential for causing lots and LOTS of bother. Especially since the source code of the malware has been published on the cyber-underground forums, meaning the techniques are openly available to just anyone who might have an interest in this – and that includes the mass of amateurs with Herostratic delusions of grandeur.

The owners of infected IoT devices wouldn’t have noticed that their kit took part in the attack, just the same as, right this minute, you won’t know if your IP-camera is being used for a DDoS attack on this or that respected net resource. And users will hardly be motivated by the unnoticeable jump in outgoing traffic to get some basic protection for their gadgets (as basic as a new login and password). However, there are other cyberthreats that are far less benign which can turn a smart home into an awful nightmare while emptying the contents of its owner’s wallet.”

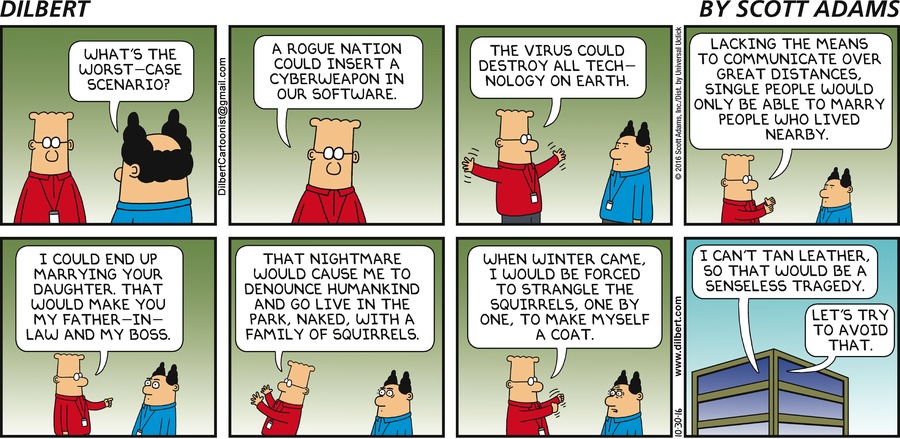

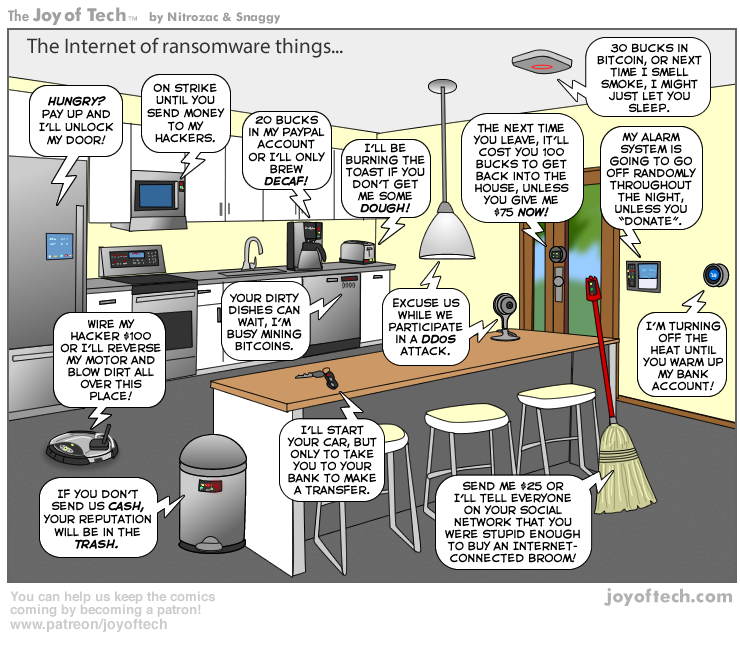

And this brings up what Kaspersky calls “The Phantom Menace”: cyber-extortionists. The ransomware business is doing great. Enter billions of vulnerable IoT devices – right on cue. Sadly, the owners of smart fridges and tumble dryers think their kit is of no interest to the cyber-baddies. Well, in a way, they’re right: the cybercriminals aren’t interested in fridges and tumble dryers – but they’d be very interested in receiving a ransom for them. It’s where we are headed:

“Your front door won’t open? The heating’s shut down in the dead of winter? The coffee machine won’t stop emitting espresso, no matter what you do? The TV’s gone all Poltergeist? The Hoover’s doing the fandango? Alas, these hacking examples aren’t science fiction; they could easily occur in reality.”

Obviously Kaspersky is ready to help with specialized expertise and ready-made solutions. And they offered some basic security for all your IoT kit, including routers, printers and everything else:

- First: Change the logins and passwords, even if they’re already not the default ones.

- Second: Install the latest patches from the manufacturers’ sites.

- Third: Put a reminder in your phone or organizer for every three months to do the above two things.

2. Data ethics, everything-as-a-service and … ummm … litigation as a driver?

There was an excellent panel on “data ethics” that went into a pretty wide-ranging data discussion .. much of it off the intended topic but what the hell. Giulio Coraggio of the international law firm DLA Piper noted that the future of personal data sharing is that “everything will become as-a-service and nobody will own any property outright ever again”. He said:

“With the digital innovation we will not own anything. We will not own our car, there will be car sharing; we will not own our house. Everything will become as-a-service. People who now don’t care much about their privacy, they will see their privacy as their main asset.”

Uplifting stuff, for sure. But he makes a good point: the old adage about the user himself being the saleable product of free-to-use services holds true today, looking at social media networks. Countered David Blaszkowski, a former regulator and the MD of the Financial Services Collaborative:

“We should think about data ethics as an industry-wide obligation. The IoT industry has the chance from the beginning to do the right thing.”

Whether or not it had or has the chance to do the right thing is debatable. Prith Banerjee, CTO of Schneider Electric, made a point with a metaphor about a driverless car deciding to plunge into a bus full of schoolkids: “40 children may die!”

Alarming stuff, but not quite on the topic of “data ethics” which was the title of the panel. Coraggio made another brilliant point:

“A machine collects so much info that it’s almost impossible to understand why it took the decision to go off the road or to crash into the bus. If we tackle these issues you’ll have to structure your technology to make some ethical decisions. Otherwise it’ll be potential litigation, and litigation certainly will be triggered if your car goes into a bus with 40 children; you will lose.”

Edy Liongosari, chief research scientist and global MD of Accenture, the discussion moderator, did try and get things back on track with this question:

“How should we be thinking about the ethics part of this? What can people do?”

Sven Schrecker, Intel’s chief architect for IoT security solutions, said that lawyers should definitely not be left in charge of making the IoT industry pay attention to data ethics:

“A bad way to solve this problem is with litigation. Put liability on and those business drivers will go the wrong way: ‘maybe I can afford to be sued?’ One way to do it, but not a good way.”

As for the data being quietly slurped up about you and me and stored for later analysis, Schrecker hit the nail on the head when he said:

“The privacy violations are not a single exposure or release of info, but an aggregation of little, unrelated pieces of information where, when you put them together, you see a completely different picture. Over time, without knowing it, we have given up these little morsels of information. We’ve actually given up a great deal of privacy.”

Panellist Derek O’Halloran contemplated the scale of the task facing the minority of the IoT industry that actually takes data privacy seriously:

“If all we had to do was solve the problem for privacy, our jobs would be a lot easier. If all we had to do was solve for security, everything would be fine. If all we had to do was solve for economic activity, we’d open it all up. It’s the balance between these that makes it so different.”

A wise observation, and one that put the extended robocar-bus-mass-child-killing metaphor into perspective. Scaremongering helps nobody and has already caused large chunks of the non-technical world to tune out security warnings almost completely. Considering the real problems that can – and need to – be solved today is the key.

O’Halloran concluded:

“This balance between what’s good for the individual and what’s good for society, how do we resolve that? We’re not going to resolve it because it’ll be an ongoing discussion, as it always has been.”

The problem as I see it is that people’s choices are being taken over by overzealous and misinformed corporate marketers – from my perspective, the evil ones. It is imperative that people take control and ownership of the technology they use and that it not dictate their choices. I am reminded of this quote by Napoleon Bonaparte: “Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide.”

Problem is, a lot of people actually like having their minds made up for them. It’s like they fear that thinking for themselves will hurt or something – perfect for the everything-is-a-service scenario.

John Veti, an attorney with whom I attend most of these conferences (and quite the wordsmith) proffered this:

“Not all choices are equal, though. There is such a thing as ‘I don’t give a flying fornication’

Imagine if you got into a taxi, told the driver your destination, and she responded with “Would you like to optimize your route for time, price, or emissions?” You’re in a hurry, so you reply “Time”. “Would you like me to break the speed limit slightly?” Hmm, tricky – if you say “no” then obviously it’ll take longer, but if you say “yes”, does that make you jointly liable when she breaks it? Is she recording this? Now you’ve placed me in a dilemma, and I wanted to spend the journey mentally preparing for an interview.”

A fellow attendee rejoined:

“There’s such a thing as “too much choice”. I want service providers to make a lot of choices on my behalf. I regard it as the height of laziness when they badger me for all these decisions that they should have been able to take for me.”

Ok, star. But what happens when your (in)decision comes back to bite you in the butt? Because everything is a decision: including deciding whether or not to decide. Everyone has an opinion: even no opinion (which is simply indifference). And every decision can have consequences. Sure you may say not to give a soaring screw … until you learn your indifference has turned into a liability.

And an interesting side note …

In the swamp of this year’s U.S. presidential election, some stories get coverage but not in depth. The Yahoo email scanning program was one which I briefly covered here.

The Yahoo mass-email scanning program was done at the behest of the NSA. Done under an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a secret tribunal. Not pursuant to a U.S. Federal Court, within the requirements of the 4th Amendment (an amendment that was long ago shredded).

Allegedly the USA Freedom Act (which constitutes the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court) requires the executive branch to declassify Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinions that involve novel interpretations of laws or the Constitution. The intelligence officials said the Yahoo order resembled “other requests for monitoring online communications of suspected terrorists”. Without detailing those orders. They continue to stonewall.